Reviewed by Drew Ninnis.

Country: USA

Director: Phillip Noyce

Screenplay: Michael Mitnick, Robert B. Weide. Book by Lois Lowry.

Runtime: 97 minutes.

Cast: Brenton Thwaites, Jeff Bridges, Meryl Streep, Odeya Rush.

Trailer: “[Jeff Bridges:] mumble, mumble, mumble.”

Plot: Set in a utopian society at some point after a great calamity, The Giver follows young Jonas, who is selected to replace the Receiver of Memories as the sole custodian of humanity’s history. But all is not well; and as Jonas slowly awakes to the ideas, emotions, and freedoms that the ruling council would keep suppressed, he embarks on a course of rebellion which may threaten their entire society.

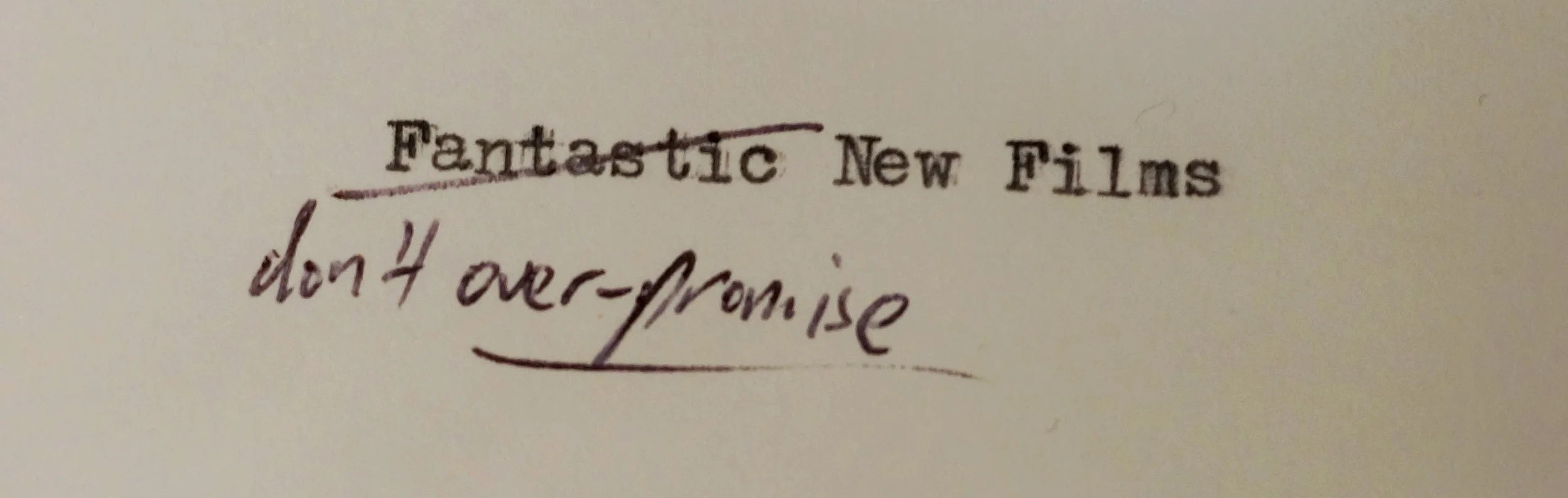

Review: I’m quietly impressed by Phillip Noyce’s adaption of the classic children’s novel The Giver. The film lightly stages a good contest of ideas for young adults and other audiences alike. The material the novel provides is excellent, turning young adult minds to contemplating the complex traditions of political philosophy and rationality that have shaped the West’s social order over centuries. At the same time, it is a gripping yarn about a young boy rebelling against the stifling conventions of his society and searching the past for clues to achieving a different present. With a script by Michael Mitnick and Robert B. Weide, the film spends just enough time world building and establishing the innocent time of youth, before delivering epoch-changing stakes as our protagonists advance into adulthood and their separate paths. Noyce’s direction is competent, and never gets in the way, while establishing a smooth pace for the film. The performances are solid, although the sets remind one a little of a Star Trek: The Next Generation civilisation-of-the-week. Overall, The Giver is a film worth seeing by young and old alike – identifying that any order is based on a fundamental decision about the nature of human beings and the resulting political rationality.

But what are those epoch-changing stakes? The argument that The Giver buys into is one that is simultaneously extremely modern and possibly the oldest discussion known to Western knowledge – that of a radical individualism against the utopian city. First, a little explanation of Noyce and Lowry’s fictional creation. After some decisive point of ruin in humanity’s past, a community constitutes itself with a strict set of rules and the ambition to eliminate all disharmony among its members, ‘a world where differences aren’t allowed’ it is remarked. What this involves is slowly revealed to the audience; initially beginning with a strict educational system, and the paternalistic allocation of jobs and places, it quickly degenerates into the more sinister. The first marker of this brave, new world is a constant reminder to strive for ‘precision of language’ – an attempt to clearly and acceptably express whatever it is one is attempting to say, without misunderstanding but with extreme politeness. We quickly discover that this extends to the elimination of words such as ‘love’ as antiquated, and other similar expressions. The audience quickly discovers that certain concepts and experiences are entirely missing and unknown – such as pain and death. Following this is the discovery that the community is heavily medicated, and every aspect of their lives kept unrelentingly equal and free of emotion – in an attempt to eliminate a core driver of disharmony. Whatever the cause of the ruin, this is a community that was at one point willing to pay a high price to avoid it and conflict at all costs.

Every utopia (from The Republic, to More’s Utopia, to Calvin’s Geneva and beyond) is based upon a thinker’s definition of human nature (from the Pelagean ‘man is fundamentally good’ to the Augustinian ‘man is fundamentally evil’ and anything inbetween). Part of the fun of any presentation of a utopia is figuring out what their position is, and how the logic of this position translates into their illustration of a society. This is certainly one of the chief joys of The Giver; where toys are called ‘comfort elements,’ dancing is banned like the town from Footloose (sadly, no John Lithgow), where there are ‘so many secrets’ and shots of ominous security cameras. In a Foucaultian turn, a teenager echoes that ‘the elders are always right’ and is convinced that the operation of their power is invincible and operates everywhere perfectly, even as main character Jonas (Brenton Thwaites – another of those generic, thick eyebrowed, square jawed, sunken eyed, high cheekboned, clean cut and credulous cookie-cutter disposable leads Hollywood is churning out at the moment, like every young male on The Leftovers) slowly realises this is not the case and that the story of that seamless operation is more critical than the operation of the power itself. The philosophical question The Giver illustrates perfectly is that the concept of the individual that is sold to the society determines everything; and that political rationality is less a question of who is right, but more a question of who gets to decide the particular rationality an order should be based upon.

Against this interestingly communal and utopian background is our hero, Jonas. At a graduation ceremony marking the transition phases of life, he is the only individual among his friends not given an occupation to pursue. It’s worth pausing to consider the ceremony itself for a minute, nicely staged and under-emphasised by Noice. Our villain, a calm and controlled Meryl Streep, appears via hologram as the chief elder and matriarch of the community to preside over the ceremony. ‘We honour your differences because today they determine your future,’ she remarks. The children who turn nine are given bikes; those turning sixteen are given their occupations; and those turning sixty are ‘retired to elsewhere’ (one of the revelations the audience can see coming, but appropriately the society deprived of a concept of death cannot). The ceremony itself reminded me of the riddle the Sphinx delivers to Oedipus and he successfully solves. You may think you know it, but actually you probably don’t. The modern version of the riddle is: ‘What goes on four feet in the morning, two feet at noon, and three feet in the evening?’ The answer, by common declaration, is ‘man’ who is a crawling baby in the morning, upright at noon, and an old man with a cane by evening. But consider the longer riddle recounted by Athenaeus, which goes:

A thing there is whose voice is one;

Whose feet are four and two and three.

So mutable a thing is none

That moves in earth or sky or sea.

When on most feet this thing doth go,

Its strength is weakest and its pace most slow.

The now commonly known riddle is a romanticised version; it refers to the human individual, and their experience as a linear chronology of events across a life. This is the version we would associate with Oedipus, the man; the individual who asserts himself in the face of the undifferentiated community, the fates, and the gods. Reconsider the second riddle though – it refers to the things in the earth, the sky, the sea. Surprisingly, the answer to this riddle could be ‘the society’ or ‘the community’ or ‘the city;’ it has at any time the grown, the aged, and the young. It has kept beasts, and boats, and birds, and homes. It is ‘so mutable a thing’ in that it is everywhere, and yet not embodied in a single person or brick. The most important feature is that it’s ‘voice is one,’ it is a polis which has many members, but ultimately only one authority and will. The children and the cattle are most vulnerable and yet most essential. In Oedipus Rex the tragic confrontation is between the great man and a blind priest Teiresias; with Oedipus snatching the decisive answer from the air – man! – while Teiresias “sees” (and Oedipus will famously, too, when he gouges out his own eyes) by realising the tragedy of this answer, and the complexity of the alternative riddle. Oedipus solves the riddle of the Sphinx and seals his doom (one which is shared by Thebes, for his shortsightedness).

I raise this because this is the oldest tension within Western political rationality; the conflict of the demands of the individual against the good of the State, and much political philosophy since the Greeks is an ongoing conversation to balance these competing poles or strike them out altogether. This is the long debate into which The Giver inserts itself, portraying a utopian community that exists in the face of the worst history of human conflict. The skill of the film is to almost convince us that these draconian measures to ensure the cohesion of the community are correct; indeed, it is only a later sinister discovery that will tip most viewers over the edge. But the film’s, and the book’s, means of disrupting this harmony is exceedingly clever. Jonas is selected to replace the current ‘Receiver of Memories,’ meaning that he will be the one individual allowed to feel, lie, experience the past, have the rules suspended, and be enabled as a full individual within this carefully proscribed role. The Receiver is the one individual allowed to be an individual; in the hope that his dangerous knowledge and experience might still be of use to the community in times of crisis. Of course, once one combines youth and the experience of a hidden world that crisis is not long in coming.

What Noyce and Lowry place into this political order is one of the newest elements of political discourse – not the Oedipal, Greek concept of the individual but its rebirthed form of the romantic individual. Consider just how radically new the romantic individual is – in terms of 2,500 years of Western political philosophy. Oedipus is one man; and one that is heftily condemned for stepping beyond the limits of man and community in the ancient world. The romantic individual is celebrated for just this act. Upon seeing these new sights and experiencing new feelings, Jonas wishes to share them with his friends and with everyone – questioning the order that would keep these human experiences separate from the rest of the community. The cinematography helps this along – conveying in supremely aesthetic terms (the hallmark of the romantic individual, as opposed to say the learning of the Renaissance man), showing the realisation of this dimension of humanness in terms of full colour and unique experiences such as sledding down a snowy slope. The romantic individual is not a celebration of a particular individual – for example, a leader or a genius – and the good they bring to the community, but an existential celebration of the capacity of every individual to experience the mysteries of the world and existence. The artist is the culminating celebration of this figure; but ultimately, the romantic individual is empowered with the ability to choose. It is a short step to the revolutionary ideals of every person having the ‘right’ to choose and to direct their own fate. This is about as far from the Greeks as one could get; Plato’s concept of the good man and the Good is one of moral absolutism, in that those who know what is good do not choose but are compelled by knowing what is right.

I’m not really qualified to argue when the Romantic Individual emerges; but one would guess it was about the time of the industrial revolution, when it was possible for a single individual to dramatically change their economic status. With the rise of the middle class, it also became possible to translate changes in the economic order into the political sphere in a manner not before seen. More money outside the hands of aristocrats meant that money that previously supported the leisure of the landed could now generate time and other pursuits for the middle class. Additionally, this cuts the ties which bound the traditional Renaissance men or artists or thinkers, who depended on the patronage of an elite. Thus the class of romantic revolutionaries in the 18th and 19th centuries; educated by a change in the possession of capital, and ready to fight for the newly discovered rights of the individual.

But The Giver is not about the Romantic individual at all, rather an even more modern incarnation. The previous Receiver, now titled the Giver, must transfer all of the memories he carries to Jonas; and as is foreshadowed heavily, he has failed in this task before and caused the suicide of his previous student. The reason is the weight of these memories; they are not all of joyous aesthetic experiences, but also deep suffering, conflict, and depravity – the fallen state of man. He transfers many of these memories in oneClockwork Orange-like montage; and illustrates why Jeff Bridges’ portrayal of the Giver is as an unruly man who stands at odds with the council of elders to which he belongs. To counterpoint his performance is prim the Chief Justice (Katie Holmes plays a judicial shrew in an act that strangely suits her), who stands in for an unquestioning adherence to the status quo and also happens to be responsible for parenting Jonas. (In a nice Platonic touch, parents to not know which children are theirs, but act as custodians and guides to the community’s children, rather like the Guardians in The Republic, where Plato instilled this separation to discourage nepotism.) To embrace this sort of individualism is to embrace suffering, disharmony, and the ability to do wrong. In a late showdown between the Giver and the Chief Elder, he pleads ‘with love comes faith, hope,’ while she responds ‘when people have the freedom to choose they choose wrong every single time.’

I’d call this Nietzschean individualism; a sort of radical individualism that is celebrated not despite but because of its horrifying shortcomings. Nietzsche, throughout his work, is at pains not to sugar coat this reality – it is built on suffering, and worse than that, in that any meaningful or worthwhile human flowering happens to a mere few, who have their charmed position in life built on the backs of the slavery of others. The Romantic individual turns into the Nietzschean individual not because they fundamentally indulge in, and have the resources for, self making but because the former has a naïve ‘beauty is truth, truth beauty’ mentality while Nietzsche maintains that everything worthwhile is not done despite the ugliness but because of it; because it can transform this ugliness into something of worth. Nietzsche differentiates between Socrates (who he ranks as a pre-Socratic, as engaged with the nature of the world) and Plato (who he accuses of the worst act of jealously and pettiness, remaking Socrates’ image to represent his own frustrated will), writing:

In origin, Socrates belonged to the lowest class: Socrates was a plebeian. We know, we can still see for ourselves, how ugly he was. But ugliness, in itself an objection, is among the Greeks almost a refutation. Was Socrates a Greek at all? Ugliness is often enough the expression of a development that has been crossed, thwarted by crossing. Or it appears as declining development. The anthropologists among the criminologists tell us that the typical criminal is ugly: monstrum in fronte, monstrum in animo. [“monster in face, monster in soul”] But the criminal is a decadent. Was Socrates a typical criminal? At least that would not be contradicted by the famous judgment of the physiognomist which sounded so offensive to the friends of Socrates. A foreigner who knew about faces once passed through Athens and told Socrates to his face that he was amonstrum -- that he harbored in himself all the bad vices and appetites. And Socrates merely answered: "You know me, sir!"

…

But Socrates guessed even more. He saw through his noble Athenians; he comprehended that his own case, his idiosyncrasy, was no longer exceptional. The same kind of degeneration was quietly developing everywhere: old Athens was coming to an end. And Socrates understood that all the world needed him -- his means, his cure, his personal artifice of self-preservation. Everywhere the instincts were in anarchy everywhere one was within five paces of excess: monstrum in animo was the general danger. "The impulses want to play the tyrant; one must invent a counter-tyrant who is stronger.” When the physiognomist had revealed to Socrates who he was -- a cave of bad appetites -- the great master of irony let slip another word which is the key to his character. "This is true," he said, "but I mastered them all." How did Socrates become master over himself? His case was, at bottom, merely the extreme case, only the most striking instance of what was then beginning to be a universal distress: no one was any longer master over himself, the instincts turned against each other. He fascinated, being this extreme case; his awe-inspiring ugliness proclaimed him as such to all who could see: he fascinated, of course, even more as an answer, a solution, an apparent cure of this case.

Nietzschean self-making is something extraordinarily different to any romantic conception; it begins and ends with the monstrous, it is often in the face of the most reprehensible, and it often has to create something as equally reprehensible in order to master itself. No easy romanticism here; and no aesthetic certainties. In The Twilight of the Idols, Nietzsche performs that often perplexing task of admiring a figure while demolishing them; just as he celebrates Christ and other transformative religious figures, just as he shatters the tablets these law givers deliver to the world. Socrates becomes master of himself only through confronting the ugliest; through battling it, and in doing so producing a counter-tyrant that is equally as ugly.

What does this have to do with The Giver? Well, here we have the central political dilemma of the film, so lightly illustrating the fundamental antinomy that drives Western politics and political rationality. The film presents the community sympathetically; it is safe and secure in the loss of its memories. The cost it pays for this is extremely high, sacrificing all freedom (and there is no bullshitHandmaid’s Tale of hypocrisy to let us off easy and lazily blame the powered elites; the Chief Elder isn’t exempt from the rules either and must work to sustain the system). Jonas can cross a border far from the community, sending himself into exile, but deliver memory and individualism back to the community. But it comes at the horrifying cost of knowing suffering, knowing pain, knowing the crimes of humanity – instantly delivered to every member of the community. Of course he chooses to do just this, but he does so only with a lightness that can be ascribed to youth. The film also overplays its hand in this respect; loading the stakes with some other imminent events that may be avoided if he crosses the threshold. Streep’s Chief Elder, on the other hand, seeks to prevent this – foolishly charging his best friend, now a drone pilot, to ‘find him, lose him’ and indicating her intent by flicking a piece of lint off her robe like a latter-day Tarquinius Superbus.

But think about that decision that he must make for a moment; treat it a little more seriously than Jonas does. There is a famous thought experiment from Nietzsche that always haunts me; in order to avoid nihilism, and encourage us into the form of self making, Nietzsche asks us to consider this:

The greatest weight. – What, if some day or night a demon were to steal after you into your loneliest loneliness and say to you: “This life as you now live it and have lived it, you will have to live once more and innumerable times more; and there will be nothing new in it, but every pain and every joy and every thought and sigh and everything unutterably small or great in your life will have to return to you, all in the same succession and sequence – even this spider and this moonlight between the trees, and even this moment and I myself. The eternal hourglass of existence is turned upside down again and again, and you with it, speck of dust!”

Would you not throw yourself down and gnash your teeth and curse the demon who spoke thus? Or have you once experienced a tremendous moment when you would have answered him: “You are a god and never have I heard anything more divine.” If this thought gained possession of you, it would change you as you are or perhaps crush you. The question in each and every thing, “Do you desire this once more and innumerable times more?” would lie upon your actions as the greatest weight. Or how well disposed would you have to become yourself and to life to crave nothing more fervently than this ultimate eternal confirmation and seal?

This is what we now call the concept of the “eternal recurrence”, and it asks the key question – if you had to live your life over and over again, would it be a blessing or a curse? It is a very personal question, and one that is probably not easy to answer out loud. As Nietzsche points out, some of us would be overjoyed and others of us would look back over our past and despair. But it asks more than this; it asks us not to regret. To look back on our pasts, and to contemplate what they could have been is fruitless, they cannot change and will never change. If we were to live again and again, they would be the same, they would be set in stone – every large and small tragedy, every large and small joy.

But here is where the sting is; would you change what you did now? Tomorrow? Would you act differently in the future, knowing that you had to live these moments over and over again? What would you do differently, how would you evaluate your life? Nietzsche doesn’t tell us what to do, but he offers us this little allegory, this little tale, which I think if one thinks about hard enough can entirely change one’s perspective on every decision one makes.

There are other problems with this allegory. Consider me for example, say I wished to live my life over and over again. Now the greatest part of my life are my philosophical studies, and my research. Now I write about, among other things, the Nazi regime and the Holocaust. If I wish to live my life over and over again, without change, am I wishing to sentence six million Jews to death over and over again? I think that it is a tough question, it doesn’t have an easy answer – there is one sense in which I am not at all responsible for what happened, the past is the past, and Nietzsche feels I should not regret or rue it – because that is what a weaker character would do – but it embrace it. And yet, and yet… some elements of the past, some things, are just too much to embrace and too much to swallow, and here we come to the danger of Nietzsche’s philosophy. It is gloriously amoral, it delights in moving beyond good and evil, and it delights in overcoming petty moral prejudices; in struggling and gaining power in order to become greater individuals, to become works of art, to resemble the great figures of history. But it does so mercilessly, pitilessly – and Nietzsche scorns pity as a weak sentiment the herd tries to engender in us to control us – it is a philosophy at all costs.

This is the radical trouble of Nietzschean individualism. Whereas the Romantic individual is beholden to no one, simply a flaneuropen to experiencing the world, the Nietzschean individual is burdened with the impossible lightness of being. A phrase that reflects the crushing nature of a modern moral and ethical burden (Simon Critchley calls it ‘infinately demanding’). Think again of Jonas’ choice; in crossing that threshold he returns the burden of Nietzschean individualism, and the reckoning or accounting that they must come to with that impossible burden.

The Giver is ultimately an argument for the status quo – our status quo, and with a statement ‘you have the courage, let me give you the strength’ Jeff Bridges ignites a montage of Tiananmen Square, the 1960s protest against the Vietnam war, and many other acts of bravery. The film’s conclusion is inevitable; and unfortunately all of the burdens, the horrors of Nietzschean individualism, go largely unexplored. But this does not prevent the audience from being disquieted by it. And although I haven’t read Lowry’s follow-on books, I would guess that Jonas’ act of radical individualism is part of a cycle where the community is shaken, slowly reconstitutes itself, slowly yields its newfound powers of individualism, and is then ripe to be shaken up again by a new young receiver of memories. This seems to be the strange loop our political systems of the last century have trapped us in; and one that is being commonly re-illustrated through many films such as The Giver.

But the dialectic is old; it is contained right there, in an ancient scene between Teiresias and Oedipus over the meaning of a riddle, and it is dramatically intensified by the economic, political, and social systems that all work to constitute some of us as Nietzschean individuals. Most of the people who will walk out of cinemas are part of a priviledged class, who posses the ability and economic means to contemplate these mysteries. But Nietzsche would highlight that this position of priviledge – yes, a little more general than it used to be, but not much – that is built on a continual foundation of slavery, suffering, and conflict. It is an inevitable part of the human condition; and while crossing a border to restore memory to the community is nice, the status quo does not shield us from our own, personal confrontation with these realities.

Rating: Four stars.