Reviewed by Drew Ninnis

Country: United Kingdom

Director: Uberto Pasolini

Screenplay: Uberto Pasolini

Runtime: 92 minutes

Cast: Eddie Marsan, Joanne Froggatt, Karen Drury, Andrew Buchan

Trailer: "What news from the land of the living?"

Plot: Lifeless protagonist John May is employed by his local council to arrange funerals and locate relatives for those who die alone within a borough of South London. When a council reorganisation brings this to an end, May makes it his mission to create an appropriate send-off for his final case, Billy Stokes. This brings him into contact with alienated daughter Kelly, and a cast of similarly predictable characters from Billy’s past.

Review: As I entered the theatre, a sea of silver hair spilled before me, with only the occasional pop of rebellious red/purple to break the tide. I experienced that sinking feeling we, for some reason, say is located in our stomach; I had forgotten that this was going to be a baby boomer film. Let me describe the concept of a baby boomer film with reference to a conversation I overheard going on behind me (I swear on all that is holy, this is true) as an aged woman described to a similarly aged friend her husband’s latest purchase:

A: No, I haven’t yet seen it, I haven’t even seen the – G – U – N. Oh, I can’t even bring myself to say it, I am that upset.

B: But isn’t it a pistol?

A: Oh yes, it’s a pistol!

That, ladies and gentlemen, is the logic of a baby boomer film – sentiment over substance, self-centred drama sliding into absurdity. A concept which Uberto Pasolini’s Still Life exemplifies.

The difficulties begin with the protagonist, John May. He is played by Eddie Marsan (and directed) to be an expressionless bureaucrat of the stoic, good-hearted variety and repeats the same hopeless mission day after day in order to give the unwanted, unloved, and departed a final moment of comfort before they are sent on their way. The wisest choice this otherwise self-pitying porridge of a film makes is to leave this past submerged, and barely hinted at – all we know is that he has no relatives, and seemingly no friends. The characterisation relies on the acts that May performs to provoke our sympathy; combined with some on-the-nose symbolism chucked in for good measure, for example when May contemplates a torn red kite stuck in a barren tree from the window of his clinical apartment (just for good measure, he is looking across into the window of his final case, Billy Stokes, who happened to live in the apartment across from him).

May seems to make no attempt to relate to the living through facial expressions or non-work related chatter; and Marsan imbues him with all the emotional resonance of an audit. Two peculiar facts about the character lead me to believe that this film might be a stealth spin-off of the blockbuster series Twilight; as May appears, for all intents and purposes, to be an emotional vampire – and a creepy one of Edward “I watch you while you sleep” Cullen proportions. Exhibit A: May appropriates family photos from the houses of the dead, ostensibly for the purposes of identifying them (?) and tracking down acquaintances, but really to keep in his home scrapbook as mementos. Photos of dead strangers. You know, like a serial killer would, or the owner-operator of a small funeral home building a portfolio. Exhibit B: May only smiles (or even reacts) when finally, after much badgering and emotional blackmail, the acquaintances he has tracked down finally break and cry, expressing the terrifying emotions and bad feeling they have been trying to block out of their lives for the past God knows how long in order to recover and be fully functional human beings. May isn’t comfortable with fully functional human beings; he prefers corpses, like him.

Then there is the acting and direction. Still Life succumbs to the sad temptation to stage itself like a West End play, giving free reign to that hollow and wooden style of dialogue and delivery that bad British theatre represents. Long monologues, where every inflection seems rehearsed and straining to sound proletarian over the unnatural RADA accents of the performers. Dialogue that seeks to emulate Brief Encounter, but comes across as stilted and affected. The cinematography and direction, particularly when documenting May’s routine, suffers from the same problem. Here the director falls into the undergraduate trap of thinking that characterisation is when a thorough, stubborn, buttoned-up character must have quirks like adjusting his office stapler so it is perfectly parallel to the rest of the stationary. May sits down to the same dinner every evening – and here, character development is telegraphed by having him eat more exotic things (like fried fish) as the film progresses – with the same routine. But rather than seeming natural, automatic, auto-pilot, the actions come across as rehearsed and repeated to within an inch of their lives. Every frame of this film comes across as unintentionally unnatural and becomes highly alienating.

And the sentiment. Still Life is predicated on the idea that with no-one there to celebrate your death, you can’t have lived a meaningful life. May is a hero because he offers these characters one shot at redemption; begging scarred acquaintances to come back to the corpse and finally make up for whatever events may have driven them apart. Yet, as May acknowledges, he generally has no idea what caused the estrangement in the first place, and seems to find it shocking that there are reasons people may not want to reconcile (the seriousness of death seems to outweigh the concerns of the living). This might be interesting; but the cases May is given through the course of the film work to support the cheap sentiment rather than confront real issues. So Billy is estranged from his colleagues because of his drinking; caused, we discover, by his time in the Falklands War. This exploitative shorthand for gaming the audience’s sympathy is used throughout the film, the issues contained within similarly never developed. It doesn’t arise that the deceased is not in contact with his family because of a history of sexual abuse, a dead child, for actions that destroyed the lives of the innocent – these problems are too hard for a film of sentiment over substance.

So that is the logic. But why is this a baby boomer film? Well, consider this snippet of dialogue from Mad Men, as Don Draper pitches an anti-smoking campaign to the American Cancer Society:

Don: What I'm suggesting is a series of commercials that run during Bandstand and the like. Show mothers and daughters or fathers and sons, and that cigarettes are between them. And you show - with a walk on the beach or baking cookies, playing catch - that the parents are not long for this world.

Board Member: But they hate their parents.

Don: They won't be thinking about their parents, they'll be thinking about themselves. That's what they do. The truth is, they're mourning for their childhood more than they're anticipating their future. Because they don't know it yet, but they don't want to die.

The generation he is referring to is the baby boomers, the flower of the sixties. And this sentiment is at the heart of Still Life; just as it is at the heart of every baby boomer film. The audience is asked to celebrate John May because it is asked to lie in the graves of the dead; it speaks to that anxiety of who will be at my funeral, who will love and celebrate me, who will remember me and make me live on after I am gone. This is why John May is made the hero of this film; and over 92 minutes an entire, narcissistic generation slowly self-indulges towards its grave. It speaks to that sea of silver hair, who fear their own deaths and celebrate the invitation to cling to life through sentiment. Never mind what the substance of that may mean; the lives that surround the deceased are of no concern within this film.

Finally, the ending of Still Life is an unbelievably cheap gut shot and redemption mechanism that I still can’t believe this undeniably exploitative film would attempt. See it for yourselves, if you wish, but watch out for the capstone sentiment.

Heidegger has some advice for the boomers, and the champions of this film, written in Being and Time – admittedly a young man’s book. He writes that the nature of our being in the world is one of ‘care’ and being ‘ahead-of-itself’; that is we care about our projects and the things we want to do, while we plan and project ourselves ahead in expectation of doing these things. But there is only death; a finality, an end, and an existence that is only on one side of that line and not the other. To project our projects, our cares, and our existences beyond that line is to indulge in a fiction. Doing this is existing in another state, of ‘Das Mann’ or with the abstract Others, a form of social and normative projection through which no one truly lives but only seems to live. He writes that living this way:

… is taken as an evasion in the face of death. That in the face of which one flees has been made visible in a way…

This is inauthenticity; a necessary way in which we must sometimes spend our time (being on someone else’s clock) but not a way to exist if we wish to understand the authentic nature of being in the world. But even the existence of this inauthenticity offers hope, because:

…inauthenticity is based on the possibility of authenticity. Inauthenticity characterizes a kind of Being into which Dasein can divert itself and has for the most part always diverted itself; but Dasein does not necessarily and constantly have to divert itself into this kind of Being.

In short, apprehending the horizon of our death, and the nothingness after it, gives value and meaning to the projects within our lives. Heidegger’s apprehension of death, rather than being morbid, focuses on finding the authentic forms of being within life.

Still Life’s John May is the antithesis of this; a horrifying character of un-death, who lives not for his own being-in-the-world but for a fictional being-of-others outside of it. The funerals he organises are the second worst form of inauthenticity; the reaction it is supposed to provoke in the audience is the worst. The supposed villain of the piece, his boss (a cartoonish despatch from “Cameron’s Britian”), has words put into his mouth which accidentally become the truest lines in the films. He remarks:

Well, anyway, the dead are dead. They’re not there, so they don’t care.

The sea of silver gasped. But in Still Life, that is the only sentiment we should applaud.

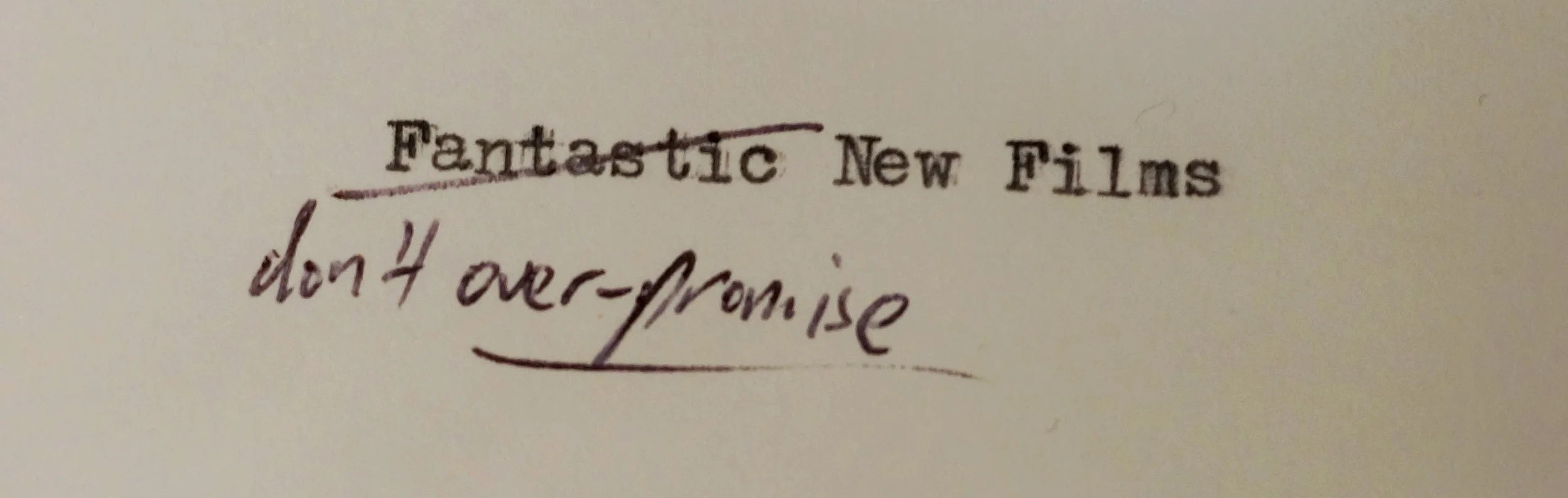

Rating: One funeral should put this cheap, maudlin film to rest.