Reviewed by Drew Ninnis.

Country: USA

Director: Atom Egoyan

Screenplay: Paul Harris Boardman, Scott Derrickson. Novel by Mara Leveritt.

Runtime: 114 minutes.

Cast: Colin Firth, Reese Witherspoon, Alessandro Nivola, James Hamrick.

Trailer: “They look like freaks. You don't look like that when you're like a normal person.” (warning: yawn.)

Plot: Loosely based on the trial of the West Memphis Three in 1994, Devil’s Knot recounts the murder of three young boys and the subsequent investigation and trial of Damien Echols, Jessie Misskelley, Jr., and Jason Baldwin. Issues with key testimony, evidence, and the police investigation abound – prompting private investigator Ron Lax to offer his services. Caught in a media firestorm and community hysteria about satanic cults, Lax must battle against all in his search for the truth.

Review: That it is sometimes difficult to discern the truth of a thing is sad, un-Socratic, and commonplace; that it can sometimes be impossible within the context of a criminal trial is a tragedy. When the media is involved, it turns from a tragedy into a firestorm. Atom Egoyan’s Devil’s Knot attempts to document, and fictionalises, just this sort of trial – of the so-called ‘West Memphis Three’ convicted of the murders of three young boys in 1994. The case itself is fascinating; full of hysteria, police incompetence, controversial rulings by the presiding judge, and a jury that does not give much faith in one’s fellow man. Unfortunately, Egoyan is not up to the task of adapting and displaying these complications or interesting facets, and the result is the equivalent of a dull made-for-television morality play minus the message.

That it is difficult to establish the truth within the context of a criminal trial should come as a surprise to no one; equally as unsurprising is that the rules and procedures of trials within the US state’s respective justice systems are by several measures deeply flawed. The film itself is based on Mara Levitt’s account of the investigation and trial from 2002; however, it hails from a long tradition of interrogation and criticism from many journalists and writers who have been captured, often first hand, by the progress of a runaway trial. One of the sharpest critics of the American legal system and its interaction with the media and politics is Janet Malcolm, who famously wrote in The Journalist and the Murderer that 'every journalist who is not too stupid or too full of himself to notice what is going on knows that what he does is morally indefensible.' What she is referring to is the technique by which journalists get close to their sources, sympathise with and cajole them, looking to extract the pearl of information that will give them a story. As many portrayals have shown – my favourite being David Simon’s brilliant Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets – a similar game is played between police and suspects, investigators and witnesses, where a suite of techniques are used to build a narrative and shape a story. One thing Simon is adept at illustrating is that when the pressure to close a case gets intense – usually through media attention, a ‘red ball’ case in Baltimore police parlance – the techniques get dirty.

By any measure, several suspicious events occurred during the investigation charted by Devil’s Knot that deserve razor sharp attention – key blood samples went missing, thirteen hour interviews were conducted of which only minutes were recorded, key witnesses seemed to fabricate and then recant their testimonies under the influence of police. Another inevitability that Malcolm traces, in her Iphigenia in Forest Hills, is that these inadequacies play out disastrously within the trial itself, leading to bad decisions and incomprehensible outcomes. Another milestone in the presentation of these difficulties has to be the breathtaking Soupçons, a documentary by Jean-Xavier de Lestrade, which was given incredible access to the defence of Michael Peterson who was tried and convicted of murder. Over the course of eight (and a follow-up ninth) episodes, the court system and the dirty secrets of mounting a case are laid bare. A key piece of evidence is found at the last minute, jury selection (and the professionals hired specifically to advise on it) is an ugly process, petty legal tactics such as a paperwork avalanche are employed, and the exit interviews with jury members will have you losing all faith in the intelligence of others. No truth could possibly survive that process; and even the principle of establishing something ‘beyond reasonable doubt’ seems a laughable ideal, and that doesn’t seem to be followed in a practical sense anyway.

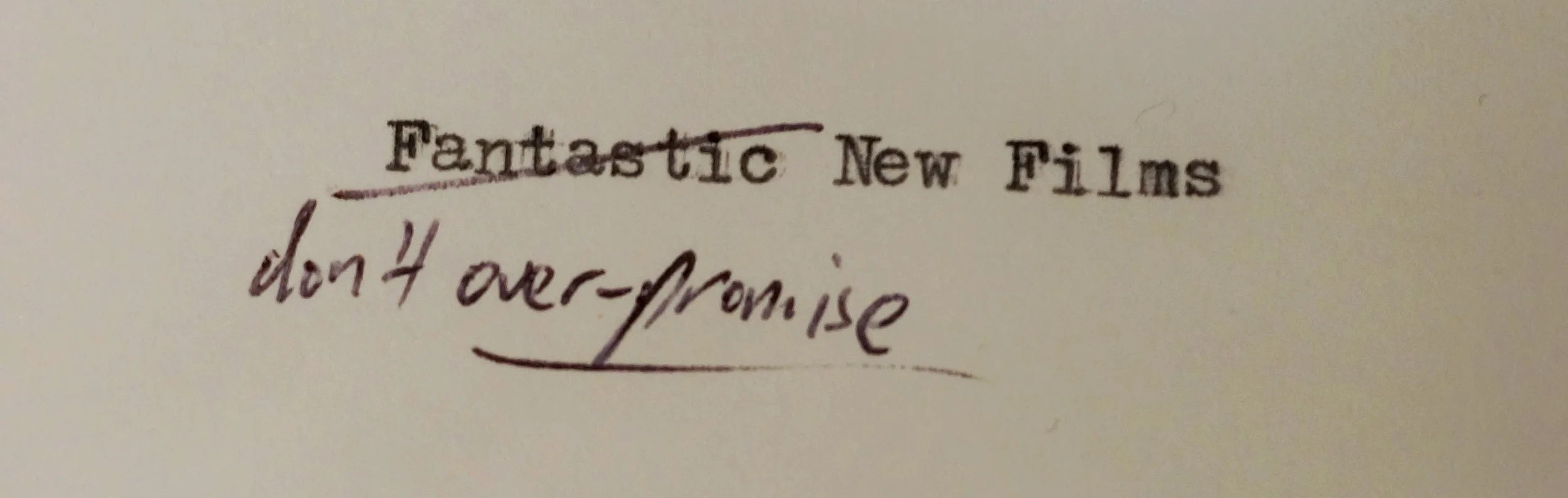

All of which is to say that any discourse which takes “truth on trial” as its subject matter has a lot of racy material to confront, and some dazzling issues to explore. But with alarming regularity films like Devil’s Knot forgo the difficult to focus on the dull – even the title, which hints at Gordian Knot but veers away at the last minute suggests the intelligence level the producers assume of their audience. Atom Egoyan is a frustratingly variable director, producing hard punches like Head On (2004), then wallowing in the unfunny in Where the Truth Lies (2005), and variations inbetween. Devil’s Knot does not play to his strengths, and the choice to tackle the case through a wealthy private investigator struggling against the system for the sake of his sense of justice does the film no favours. We are left with very little interest in the life or concerns of Ron Lax (Colin Firth), being forced to plod through his divorce and his acquisition of a $10,000 Napoleon III console table (at least that was how it was introduced, it looked suspiciously like a Louis XVI piece to me – yes, I know, fascinating; and yet this overlong film still lavishes time on it). It was also extremely unwise for Colin Firth to attempt a vaguely Southern accent; the result is Mr. Darcy doing his darndest Foghorn Leghorn impression.

The mother of one of the victims, Pam Hobbs (Reese Witherspoon), is a secondary focus for the film but not a lot of much resonance is done with her character. She pines for justice, becomes suspicious, wants to see the truth out, suspects her husband. This contributes to the unevenness of the film; and Egoyan’s poor pacing takes a fascinating case and injects it with languid periods of dullness. Bizarrely, the film also had me sympathising with Sarah Palin for its portrayal of a southern Red state, wearing as it did its contempt for small town rural America on its sleeve. Every second character is a balding, thick-waisted, redneck caricature; or a shrill, cheaply dressed 40-something female in tacky blue eye shadow. Along with dullness, laziness is a hallmark of the film, and no depth is given to any of the two dimensional characters portrayed throughout. This somewhat lessens the blow when we learn the fate of the three boys on trial.

I can’t help but feel that directors who choose to tackle these moments – these fundamental challenges to the United States as a fair and free system – have a moral responsibility to render that imperfect union in full, unflinching, intelligent detail. Anything less than that is a betrayal; because opening up sites of dialogue such as these, potential sites of progress, is the only way to improve that union and address injustice. When these very real events are turned into a cheap thriller, as it the case here, it feels like a betrayal of the individuals involved and the principles at stake.

But on a purely aesthetic level? In that case, Devil’s Knot isn’t a film worth actively seeking out; but if it happens to be on T.V. when nothing else is on, then it adequately fills the time.

Rating: Two stars.