Reviewed by Drew Ninnis

Country: USA

Director: Errol Morris

Screenplay: Errol Morris (Documentary)

Runtime: 103 minutes

Cast: Donald Rumsfeld, Errol Morris.

Trailer: “We need to understand how we got to where we are.”

Viewed as part of the Stronger Than Fiction Film Festival.

Plot: The Errol Morris documentary The Unknown Known consists almost entirely of a wide ranging interview with former US Secretary of Defense, Donald Rumsfeld. Best known as the Bush administration SECDEF at the beginning of the Afghanistan and Iraq Wars, Rumsfeld is also a veteran Republican politician and came within a whisper of being Ronald Reagan’s Vice President. The film covers his entire career, but focuses on his now infamous memo in which contemplated the “unknown unknown” and the “unknown known.”

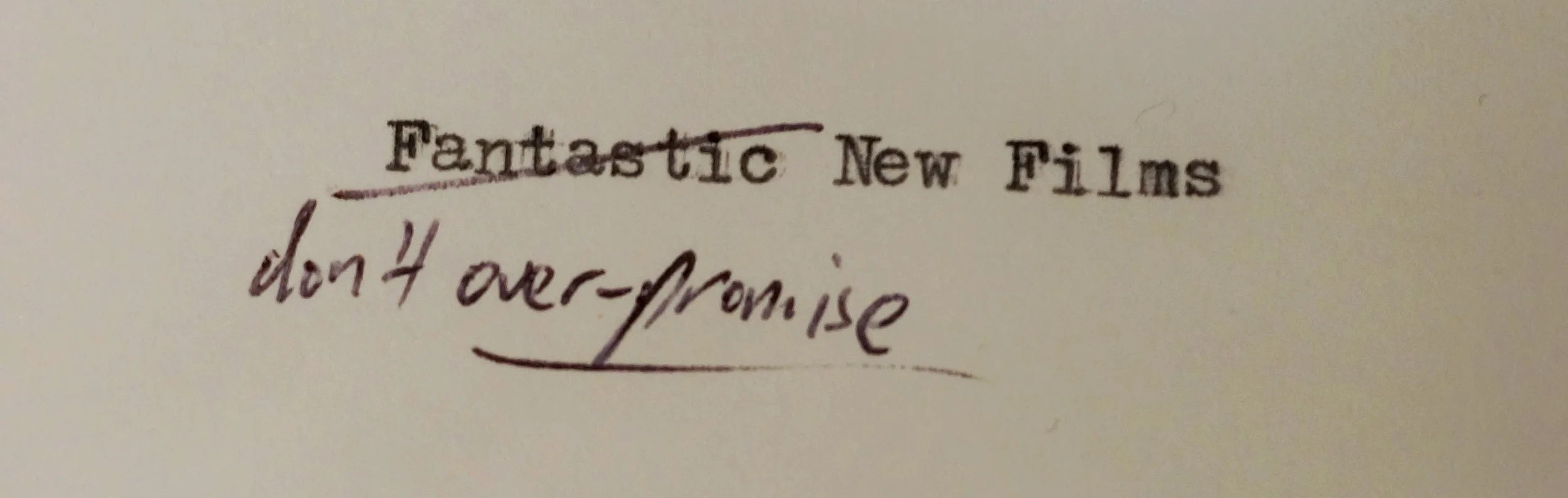

Review: Despite the many cues he so skilfully inserts, it would be very easy to misread Errol Morris’ latest documentary The Unknown Known. Those hoping for a reckoning with Donald Rumsfeld over the current state of Iraq, intelligence failures, or any of Rumsfeld’s blithe claims made as Secretary of Defense will be disappointed. But Morris makes clear, very early on, that this is not the intention of his film; instead he aims at revealing the magic and charisma that the man, Donald Rumsfeld, has deployed over a long and successful (by some standards) political career. Like Orson Well’s flawed masterpiece, F for Fake, the film attempts to pin down the sleight of hand that makes the master charlatan; like F for Fake, Morris’ quarry proves elusive, but the documentation proves ultimately enlightening.

Rumsfeld’s magic is rhetoric; he is a practiced philosophical magician, but of a dubious quality. While other politicians are content to capture a comfortable, metaphorical high ground and wait out the judgement of history – citing ‘America, Flag, Freedom’ to quote 30 Rock – Rumsfeld reveals himself as something more; as a Sophist in the old sense, a man who wants to win the argument at all costs. Part of the joy of The Unknown Known is the way Morris skilfully and quietly draws out Rumsfeld’s arguments, deconstructing them through the use of Rumsfeld’s own memos, press conferences, and testimony. Morris doesn’t confront Rumsfeld on the truth of his statements – and audience members will no doubt have their own “hey, wait a minute” moments – but instead examines the logic and the patterns in the way Rumsfeld argues.

This is an old trick; any philosopher can tell you that when cornered at a party for an argument, the most successful tactic is not to challenge the empirical basis of someone’s argument but to tease out the definitions and the coherency of what they are trying to argue, testing the limits of how far they will take their own logic and then doubling back on them with their own distinctions or assertions. This is something that Rumsfeld himself does when interviewed, and as Morris shows during his press conferences as Secretary of Defense. Many of Rumsfeld’s ‘snowflakes’ (the memos he writes to Department of Defense officials) are requests for the Pentagon’s or OED or Webster’s definitions of certain words and phrases. At one point in a conference, he pointedly demonstrates that he has followed up the press’s questioning and looked up a definition, which he will now respond with – but only one definition, from the Pentagon dictionary. Another old trick; finding and making use of the definition most favourable to your argument, in the process making an appeal to authority for the source of the definition. These are not techniques you see deployed by the average politican, who is quick to buy out of any difficult debate and reframe the terms of the discussion in the broadest possible platitudes. Not Rumsfeld, who relishes the danger and excitement of being the high school debating captain, using the power of the podium to satisfy his penchant for winning the argument.

There are several exchanges between Rumsfeld and Morris, between the very different personalities and styles of the two individuals, which are worthy of note. Morris is not David Frost; he leaves his subject room to explain at length, rather than inserting himself into the frame and jumping in for the kill. The subject naturally and gradually manifests itself within that space, as does Rumsfeld. Overall the tone is more contemplative, but one fiery moment leads to this exchange:

M: Why this obsession with Saddam and Iraq?

R: Well, you love that word - obsession. I can see the glow in your face when you say it...

M: Well, I'm an obsessive person!

M: Are you? I'm not. I'm cool and measured. If you look at the range of my memos, there might be one tenth of one percent about Iraq.

The reason I was concerned about Iraq is 'cause four-star generals would come to me and say, 'Mr. Secretary, we have a problem. Our orders are to fly over the northern part of Iraq and the southern part of Iraq on a daily basis with the Brits, and we are getting shot at. At some moment, could be tomorrow, could be next month, could be next year, one of our planes is going to be shot down and our pilots and crews are gonna be killed or they're going to be captured.'

The question will be, 'What in the world were we flying those flights for? What was the cost-benefit ratio? What was our country gaining?' So you sit down and you say, 'I think I'm gonna see if I can get the President's attention. Remind him that our planes are being shot at. Remind him that we don't have a fresh policy for Iraq, and remind him that we've got a whole range of options.' Not an obsession.

A very measured, nuanced approach. I think. [smiles]

The point goes to Rumsfeld; but only through a deft sleight of hand. He subtly reframes the exchange, playing the man and moving it to terms that are more reasonable. The spirit of the question goes unanswered – why, among the ‘Axis of Evil,’ choose this guy? Rumsfeld offers some revision to the record, stating that he didn’t believe most people thought Hussein was directly connected to Al Qaeda. Morris uses one of his filmmakers advantages – that well known Daily Show with Jon Stewart technique – of cutting to footage of Rumsfeld maintaining the opposite during a press conference. But Rumsfeld still chalks that one up – winning the linguistic argument about the term “obsession,” and causing Morris to miss his shot. Yet Morris doesn’t; he knows he’s not going to get an answer from Rumsfeld. What he does get is a shot of that sleight of hand, of a hint of how the magician does it.

Morris also deftly charts the trajectory of Rumsfeld the politician; drawing on unflattering quotes from the Nixon tapes, and following Rumsfeld’s career from the Army to being a step away from the Vice Presidency. This is a Rumsfeld that is little remembered; the man accused of easing George H. W. Bush into a position as head of the CIA in order to forestall a political competitor. Most riveting is Rumsfeld’s self-serving account of the 1980 Republican Convention in Detroit, Michigan. One of two choices for the Vice Presidency, Rumsfeld claims that his utmost concern was that Gerald Ford was not chosen for the position; claiming that his own prospects or his rivalry with George H. W. Bush were not of concern. Morris asks:

M: It seems to me that if that decision had gone a slightly different way, you would have been vice president and future president of the United States.

R: [pause] That's possible. [long pause, no smile]

The Unknown Known documents several other feints and dodges; significantly, Rumsfeld’s response to what became known as the ‘Torture Memos.’

M: What about all these so called torture memos?

R: Well, there were, what, one or two or three. I don't know the number, but there were not all of these so-called memos.

They were mischaracterized as torture memos, and they came, not out of the Bush administration per se, but they came out of the US Department of Justice, blessed by the attorney general, the senior legal official of the United States of America, having been nominated by a president and confirmed by the United States Senate overwhelmingly.

Little different cast I just put on it than the one you did. [chuckles, gestures] I'll chalk that one up.

Point Rumsfeld; but he had to play dirty to get it, picking the part of the problem he had the best chance of questioning (the media characterisation of the memos) and hoping that small victory undermines the rest of the argument. The appeal to authority is present, although largely irrelevant to the question asked. Rumsfeld uses the colour of largely unrelated details (“blessed, USA, president, confirmed overwhelmingly”) to recast the debate. He thinks he has been successful; but again, he scores the smaller point to evade the larger argument. Morris captures another moment.

The pivotal moment of the film comes from the memo that gives The Unknown Known its name. Rumsfeld reads:

February 4, 2004. Subject: What you know. There are known knowns. There are known unknowns. There are unknown unknowns. But there are also unknown knowns. That is to say, things that you think you know that it turns out you did not.

These are the words that Morris was rightfully obsessed with; as they contain a clarity that, on further examination, slowly gives way to ambiguity and sophism. They are based on a commonsense proposition – that sometimes the things we are certain about turn out to be wrong. The use to which Rumsfeld puts that insight is more troubling; as a part excuse and part weapon in a new rhetorical battle. At the time of the quote, most attention was given to Rumsfeld’s ‘unknown unknowns’ as a neat narrative in which to fit the errors and unexpected reversals of Iraq. But it is the category of ‘unknown knowns’ that is far slipperier, and holds Rumsfeld’s attention. He is obsessed with a ‘failure of imagination’ akin to Pearl Harbor; and Morris documents this thought spectacularly in a series of articles for the New York Times that accompanied the film.

Within The Unknown Known, what Morris documents is the way in which the concept Rumsfeld births ultimately defeats him:

R: If you take those words and try to connect them in each way that is possible there was at least one more combination that wasn't there: the unknown knowns. Things that you possibly may know that you don't know you know.

E: But the memo doesn't say that. It says we know less, not more, than we think we do.

R: Is that right? I reversed it? Put it up again. Let me see… [rereads] Yeah, I think that memo is backwards. I think that it's closer to what I said here than that.

We find two fabulous magic tricks have been performed here. The first is performed by Rumsfeld, and we catch him in the act, as he attempts to turn a weakness into a strength – like all good magicians or con artists. We catch him in the middle of trying to rewrite one of his most lasting intellectual products; one which remains ambivalent to the core (personally, I think either reading could be convincingly argued as the meaning of “unknown known,” indicating that perhaps the simple four could be multiplied endlessly, like Kant’s faculties and categories). It is an act worthy of any of the characters of Welles’ F for Fake – Elmyr de Hory fabricating Picassos, Clifford Irving fabricating his biography, and Welles fabricating the documentary itself. Rumsfeld is caught in one last act of fabrication.

But there is an even greater trick performed here; performed by one of the few master magicians who can outplay Rumsfeld – Errol Morris himself. Those who criticise Morris for not confronting Rumsfeld directly miss the bigger accomplishment of the film. Winning the debate matters most to Rumsfeld; on his obsession with words and definitions he states he focuses on ‘what do all those words mean ... what are the best ones to use that will benefit the United States of America.’ But Morris confronts the great debater Donald Rumsfeld with an opponent he must defeat to win the argument, but cannot – Donald Rumsfeld. Trapping him in a debate to redefine his own words against themselves.

Poor Rumsfeld forgets the most important lesson of the professional philosopher, arguer, or military commander – never engage on your opponent’s territory. The film The Unknown Known is firmly in Morris’ territory. Mr. Morris, you can chalk that one up.

Rating: Four stars.