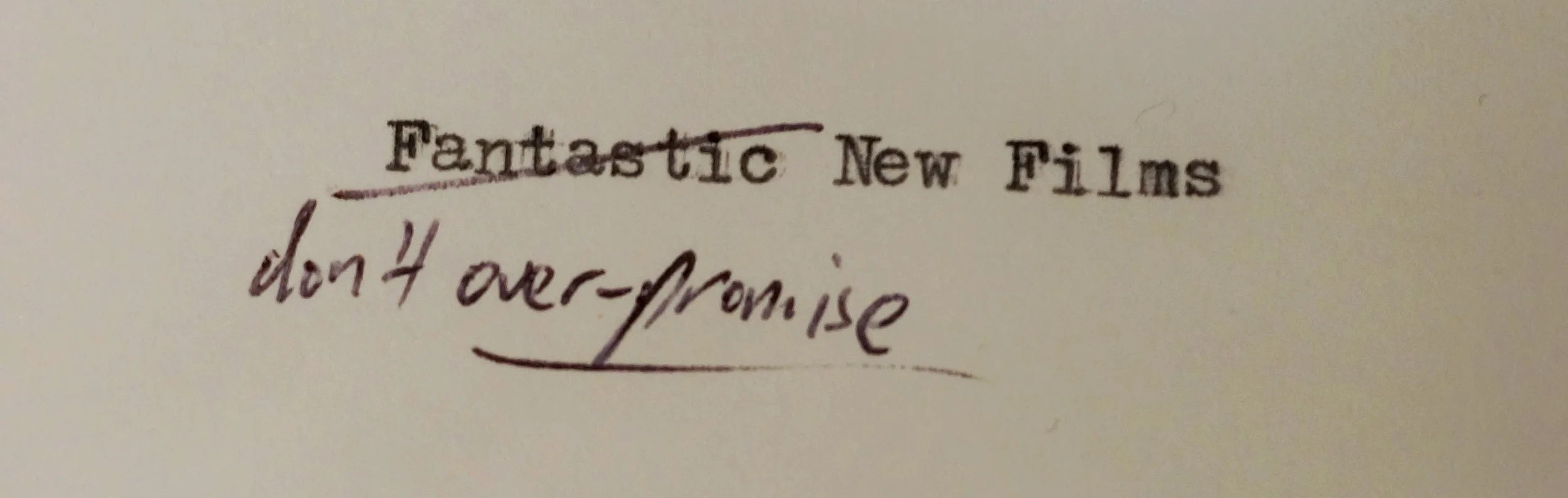

The Drop is a high school essay in heavy-handed symbolism; taking up the age old theme of crime and punishment but daringly choosing to do nothing particularly interesting with it. Penned by successful airport novelist Dennis Lehane it is a stirring reminder that not only can you not be good at everything, but that it is entirely possible to be hugely successful and not good at anything (perhaps he has a beautiful singing voice). The film is a poor send-off for the effortlessly talented James Gandolfini, and only worth seeing for his performance alone.

Country: USA

Director: Michaël R. Roskam

Screenplay: Dennis Lehane

Runtime: 106 minutes.

Cast: Tom Hardy, James Gandolfini, Matthias Schoenaerts, Noomi Rapace.

Reviewed by Drew Ninnis.

Plot: Bob tends a run-down Brooklyn bar under the cynical supervision of Cousin Marv, who used to own the joint. Now it acts as a front for Chechen gangsters, who use it as one of many locations to drop and secure money from their illegal enterprises at the close of business. Their comfortable routine is disrupted by masked robbers, who know just what they are stealing and who they are stealing from – seemingly playing a longer game to extract some bigger prize. Folded into the mess is Detective Torres; sent to investigate the crime, but quick to start looking into the dubious connections that keep the operation running. Bob and Marv are caught in an impossible position.

Review: A strange personal theology hovers over The Drop, a low-level gangster thriller directed by newcomer Michaël R. Roskam and penned by the successful airport novelist Dennis Lehane. Centred on a Brooklyn dive bar that acts as a periodic drop-off point for illegal gambling money, the straightforward setup quickly gives way to the regulation twists and turns of the genre. Our protagonist Bob, played by an increasingly proletarian Tom Hardy, tends bar and stays out of things; while his cousin Marv (James Gandolfini) nurses resentment at being pushed out of the game by the Chechen gangsters that now run the district. When a robbery occurs, carried out by masked gunman who seem to be in on a deeper long-con, things get complicated for Bob and Marv – who are forced to settle up with the Chechens, hold off an inquisitive police detective, and wait for the other shoe to drop as the robber’s plan is slowly revealed.

Three fundamental flaws in the film stick out from the beginning. The first is craftsmanship over direction; as director Roskam brings the elements together skilfully, but builds a pale and clichéd imitation of a late Nineties crime thriller. Unoriginality bleeds from every frame, beginning with the cinematography itself – long shots of Brooklyn and New York icons reflected in black puddles, with fluorescent orange and green washes; a nightime palate that only gives way to the lacklustre romance Bob conducts with the damaged Nadia (Noomi rapace) over a found puppy. Because crime is conducted at night, see, and that is when the seedy underbelly of Brooklyn reveals itself. This obviousness translates into the narration itself, and Bob opens the film with a simpleton’s declaration:

There are places in my neighbourhood no one ever thinks about. And you see them every day, and every day you forget about them, these are the places that all of the things happen that people are not allowed to see. You see in Brooklyn, money changes hands all night long…

Lets leave aside the strange phrasing of seeing a place every day you're not allowed to see, because the film's problems are deeper than its periodic awkwardness (meant to be a reflection of Bob, I suppose). It goes to the heart of the second fundamental problem, and the only interesting part of the film – Bob’s cosmogony. He is painted as an honest character in a decaying city, another unoriginal conceit in a film stuffed with them, and a man who attends the morning mass at his local Catholic church every day. Of course the narrative demands that the church must close by the end of the film, another clunky symbol in a film that is – yes, again – overstuffed with them.

The film concludes with a summation of Bob’s worldview, and the Fortinbrass declaration that is meant to constitute the anti-moral of this fool’s Hamlet:

There’s some sins that you commit that you can’t come back from, no matter how hard you try. You just can’t. You know, they say the devil is waiting for your body to quit because he knows, he knows he already owns your soul. And then I think maybe you know there’s no devil, you die and God, he says – nah, nah you can’t come in. You have to leave now. You have to leave and go away now and you have to be alone. You have to be alone forever.

let's leave aside God as nightclub bounder ('not in those fuckin' shoes, mate') because, again, the film's problems go deeper. It becomes clear, only at the close of the film, that Bob was meant to be the character study and the purpose of the film this entire time – thus we spend the vast bulk of the screen time with him as he slowly trudges his way out of a dark world seemingly not of his making. This is also why we are subjected to his ungainly romance, which needs the life support of an on-the-nose abused puppy Macguffin and pointed, painful dialogue about a broken angel statue on Bob’s kitchen table. We’re treated to this representative slice of Lehanian dialogue:

Nadia: It’s broken.

Bob: Yeah, it is.

N: Do you want me to fix it?

B: Do you want to fix it?

N: Yeah.

B: Sure. You want another beer?

N: Yeah.

[Exit, pursued by a bear.]

Cue the single, lingering piano notes meant to evoke Bob’s sadness and isolation. Fundamental problem number two is that Bob is meant to rest entirely at the centre of the film; and yet in every scene, in every viewing mind, he disappears – and not in that artful, I meant it, quiet man at the back of the room kind of way. Tom Hardy seems to yearn for the roles of Joaquin Phoenix; in the roles he has chosen and the visceral style in which he injects himself into the character (even at the risk of being incredibly, incredibly dull). But he’s not getting those parts and Paul Thomas Anderson isn’t calling; the script isn’t either, which treats Bob essentially as a cipher. Everyone else plays there character entirely differently; understanding that they are stock stereotypes in a standard setup and not attempting to make their clichés more dull through making them real.

Hardy is further, predictably, unintentionally, backgrounded by the fact that he is performing alongside of James Gandolfini. When that man enters frame – and he’s pretty critical here – it becomes impossible to see anyone else in the room. Playing an anti-Tony Soprano, a small-time loser who had his shot, Gandolfini’s charisma and presence elevates the role to something from another, greater film. Shitty dialogue doesn’t get in his way; it is the manner in which the actor can move about the centre of attention, and at the last minute turn and notice it, electrifying the scene and pinning whomever is unlucky enough to get in his way to the floor. Here he’s like that stage extra in a terrible show that seems effortlessly natural and yet unique, so mesmerising that one barely hears lines from other characters passing over his head. Gandolfini never got the film career he deserved – instead stealing a scene here and there in films like In The Loop. Here The Drop serves as a tragic reminder.

And Gandolfini isn’t the only one, as Matthias Schoenaerts appears as Nadia’s psychotic ex-boyfriend just released and extremely dangerous. In scene after scene between Hardy and Schoenaerts we are meant to be focused on what Bob’s going to do, how he’s going to handle this – but instead we’re mesmerised by Schoenaerts’ performance and the effortless, disorientating way in which he shifts tonal gears. It compensates for Noomi Rapace as Nadia, who seems to have read damaged as brittle highschool emo and is buried under the banal dialogue she’s given as a damsel in distress.

Flaw number three, and the biggest, has to be Lehane’s script. If the mindless dialogue above didn’t convince you, then the simulacra of a gangster tone and gritty street talk will. The structure of the plot – and its twists – work well enough, but seem utterly at odds with the character study the film obviously wants to forward. What starts with a sociological survey, via voiceover, of a certain sort of business in Brooklyn attempts to turn itself into a Karamazov tale at the close, as if Lehane believes that resting two tired crime tropes next to each other is as good as making them meaningfully intersect. He might have gotten away for it too, if it weren’t for that pesky shitty scriptwriting.

‘No one ever sees you coming, do they Bob?’ Detective Torres heavy-handedly concludes for us; as if the film hadn't bludgeoned us to death with its high school English class enough already. That’s probably where this film should end up too – as it is easy enough to teach, and pretty hard to enjoy. If we interpret the film in that tried and tested old way, by who gets punished at the close of the film, then the answer most certainly has to be the audience.

Rating: Two stars.