Asia Argento exorcises the ghosts of her childhood in Incompresa, a film that is interesting to watch, but doesn’t amount to much on reflection. Composed of many unique details, the story of a young and neglected girl fails to be anything startlingly original when taken from a broader perspective.

Reviewed by Drew Ninnis.

Country: Italy.

Director: Asia Argento

Screenplay: Barbara Alberti, Asia Argento.

Runtime: 103 minutes.

Cast: Giulia Salerno, Charlotte Gainsbourg, Gabriel Garko, Anna Lou Castoldi.

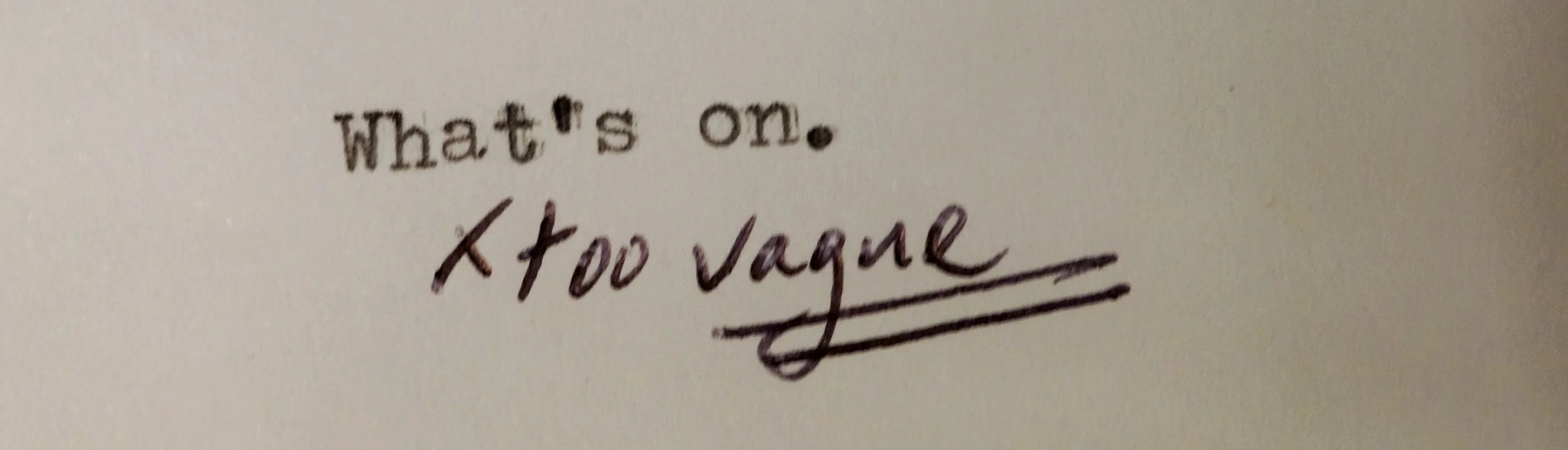

Trailer: Very unfortunate braces.

Plot: Aria is an ordinary nine-year-old girl growing up in Rome in the 1980s; one of three sisters from the blended family of a famous pianist and a famous actor. But things are not well, and as the marriage begins to disintegrate, Aria seeks refuge with her best friend and the within the lives of her classmates. Being the youngest child, and the only child of both parents, she is frequently the innocent target of her parents venom – and the film closely documents the chaos that swirls around Aria as she moves from one home to another and back again.

Festival Goers? See it.

Viewed as part of the Lavazza Italian Film Festival.

Review: It’s hard to disassociate the figure of Asia Argento from her latest film, Incompresa (Misunderstood), which one suspects is perhaps the point behind the director’s entire body of semi-autobiographical work. Argento seems to approach filmmaking as a sort of visible, validating therapy – where every gothic terror and recurring issue is portrayed then dissected on screen in the hope of catharsis and liberation. The fact that she keeps making these films, and returning to an abusive childhood, seems to indicate that it isn’t a wholly successful therapeutic approach. Does it create something interesting and meaningful for the audience, though? Perhaps, but with some broad caveats. Within the context of the festival, the film also has the deep misfortune of appearing alongside Those Happy Years – which canvasses much the same territory, but with greater accomplishment.

The biggest syndrome that Incompresa suffers from is an overbearing feeling that what it is portraying is unique and important, a narrative that is so special it has a deep emotional resonance. This is the mistake of making a very personal film; if the film does draw on semi-autobiographical elements, then this explains the film’s conviction that it is presenting something entirely original, when in fact we have seen this narrative many times before. The film illustrates an abusive childhood within a disintegrating marriage of privileged artists; a trauma that almost every significant director with a large enough body of work has plumbed at some point within their career. Therefore, the broad strokes of this film aren’t original; but the details are interesting, and the performances are excellent.

It follows nine-year old Aria (Giulia Salerno), the only child of a talented but dissolute pianist (a stately Charlotte Gainsbourg) and a successful actor seeking respectability (a cheekily cast Gabriel Garko). Both have a daughter each from previous relationships, who are treated as the respective favourite of their madre and padre. Poor Aria, the only product of their poisonous union, is a frequent casualty of their bitter feuds and finds herself short on affection but long on abuse. She turns to her best friend for comfort, and to a black stray cat that she picks up from the streets and befriends. Some small but moving moments come from Aria’s relationship with the cat, particularly as she is kicked from one parent’s apartment to another; walking the streets of Rome with her faithful friend in a cage beside her. Things are not much better at school, where she is the target of the usual childish cruelty, and has a crush on an older boy that is not returned. Unfortunately, Aria’s repeated cries for attention end in a tragic place.

So, what to make of this? Argento directs the audience immediately to the confessional nature of the project, framing the film with a voiceover which states at the outset that ‘there are many, many ways to cry; mine is the most disdainful,’ and concludes at the close of the film with ‘all of this is not for me to play the victim, but for you to get to know me.’ This is further complicated by the biographical fact that although named ‘Asia’ at her birth by her parents, Argento’s official name is ‘Aria’ as the Italian registry authorities wouldn’t accept the more exotic formulation. She picks exactly the right child actor in Giulia Salerno, whose eyes gaze out from the screen like lapis lazuli saucers and attest to her innocence. We feel deeply sorry for Aria’s circumstances, and the unfairness of the destruction that her parents wreak; but one can’t help shake the feeling that this is all presented as an excuse, as an argument from that deeply irrational place of ‘they’ll all be sorry when I’m dead.’ While the film has enough incident and beauty to maintain interest, the apologetic and self-indulgent nature of the material makes it hard for a distanced audience to find a significant message (other than casual misfortune) within the narrative. Yes, it must be impossibly tough to grow up in that environment; yes, those parents are truly awful; yes, no child should have to go through that – particularly one of wealth and privilege. But once those mandatory questions are asked and answered, I’m not sure what else we are supposed to get from this presentation.

But this assessment perhaps unfairly clouds the sometimes black humor and interest the film contains – indeed in being a straightforward, rather than melodramatic, treatment of the subject matter it makes itself into a film worth watching. One thing it truly nails is the sense of kids at play; one the one hand innocent and free, but as one scene with Barbie and Ken attests they are already playing out the dramas and the cycles of adults who should be protecting them from the world. Other elements don’t work as well – there’s a clichéd on-the-streets with vagrants and prostitutes moment that creaks with tiredness and unoriginality (although at least it doesn’t occupy the entirety of the film, like Darker than Midnight). Gainsbourg’s performance is casual, understated, and effective; although one can’t help but feel that she is a bit underused. Personally, I walked away less remembering her character and more impressed that she can act fluently and naturally in so many different languages, in so many different contexts. The other performers acquit themselves well, and the film is nicely composed and shot.

But what to take from it? That’s the question I keep returning to when I think about Incompresa and one to which I have no answer. It is interesting to watch another actualise their therapy session through art; and there’s a lot of skill here. But nothing that truly resonates beyond the photo-montage of the credits.

Rating: Three stars.