Reviewed by Drew Ninnis.

Country: Israel, USA.

Director: Nadav Schirman

Screenplay: Nadav Schirman (Documentary).

Runtime: 95 minutes.

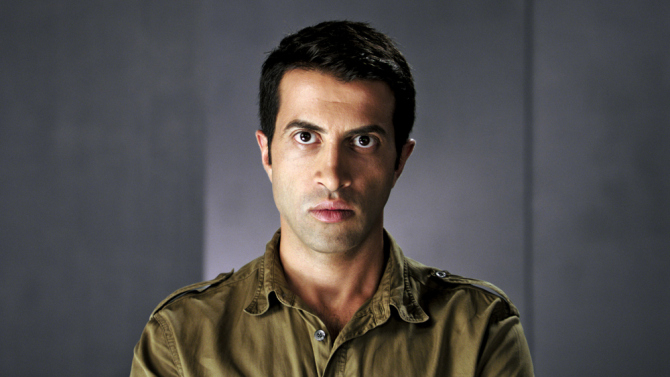

Cast: Mosab Hassan Yousef, Gonen Ben Yitzhak.

Trailer: “They needed someone like me, so I played the game.”

Viewed as part of the 2014 AICE Israeli Film Festival.

Plot: Mosab Hassan Yousef, the son of a founding member of the terrorist organisation Hamas, was recruited by Israeli internal security force Shin Bet to spy on his father and infiltrate terrorist organisations. The Green Prince, as he was called, is transformed into one of Israel’s most sensitive and effective sources of information – but at great risk to Yousef and his family. Told through complimentary interviews with Yousef and his handler Gonen Ben Yitzhak, the story they recount borders on the unbelievable.

Review: At the close of Nadav Schirman’s crowd pleasing documentary The Green Prince, Mosab Hassan Yousef describes the bond that tied the fates of himself and his Israeli security handler Gonen Ben Yitzhak together as ‘the bond of truth.’ Breathlessly the lady next to me exclaimed ‘that’s right!’ transported by the narrative of the film to some sort of place of recognition; and that certainly will be the experience of many viewers. The Green Prince tells a neatly packaged story of a Palestinian man turning against everything he believes in, betraying his family and his friends, and working with his captors and torturers to uncover the secret dealings of Hamas and protect Israeli security interests. It is undoubtedly a human interest story with honour, betrayal, and suspense; and Schirman delivers it to the audience in easily digestible, unquestioned pieces.

I am deeply suspicious of this film; and it created within me a profound concern that one of the few mediums of presenting a complicated, ambiguous portrait of certain people or moments has finally been colonised by the demand to generate easy narratives that reaffirm the worldviews of its audience. This is the exact opposite of what I find worthwhile in cinema, the challenge of cinema, and particularly the goal of a good documentary. It is disappointing to see the death of these principles so warmly embraced by the crowd. But as Kierkegaard said, the crowd is untruth – so perhaps it is simply getting the narratives it demands.

At the heart of The Green Prince is a series of duelling interviews with source Mosab Hassan Yousef and his Shin Bet handler Gonen Ben Yitzhak. Within the telling of the film, Yousef is wedded to the terrorist organisation of Hamas through the influence of his father Hassan Yousef (a founding member of the group), and the constant persecution the family suffers from Israeli security forces in the form of arrests, detentions, and numerous prison terms. At the age of nineteen, Yousef purchases handguns from a contact in the desert, is stopped by checkpoint guards, and arrested. Yitzhak and his colleagues attempt to recruit Yousef while he is imprisoned, pressing him to report on activities within Palestinian Authority jails. On his release, Yousef is further pressured to report on the activities of his father and his colleagues; becoming the right hand man of one of the most powerful Hamas figures within the West Bank, but also becoming Israel’s most valuable source. Both Yousef and Yitzhak face difficult choices; needing to protect Yousef’s father from assassination, maintain Yousef’s cover as a loyal member of Hamas, and balance the interests of security against a long term intelligence operation. The account they give is riveting and suspenseful; at any moment one or all of these things could go wrong.

But the format of duelling testimonies is itself problematic, and goes to the heart of the truthfulness of the film. Schirman is not confident in the attention span or seriousness of his audience, and sets out to create a slick 24-like recreation with a well rehearsed Yousef reciting his lines as emotionally as possible within the simulacrum of a prison. Yitzhak is more sanguine; delivering his account in a straightforward interview-in-a-hotel manner. Schirman mixes these interviews with footage from the events and news reports, as one would expect, but also with dramatic re-enactments of Yitzhak driving determinedly and Yousef being interrogated or languishing within his cell. Over the top of this are simulated shots of drone strikes, special forces raids, pick-ups and drop-offs, a thudding soundtrack, and every additional element that the director can throw in to get the pulse racing. The overdetermined nature of the documentary, not letting a single manipulative tool pass unused, gives the audience no room to breathe and think. You are meant to be swept along with the wild ups and downs of the narrative; turning a delicate story into a bruising thriller.

Part of this is a conscious choice on behalf of the director to leave the politics out of the narrative, in so far as that is possible with a story that has violence and politics at its heart. Thus the focus on the bond of these two men, their loyalty to each other (and it is emphasised how important it is to Yousef that Yitzhak breaks Shin Bet protocol to speak to him alone, showing trust). An equivalency isn’t established between Hamas and Israeli security forces, the latter are largely given a pass while the former are taken for granted as barbaric and hateful. I don’t particularly wish to challenge that assessment or those views; but I do find it problematic that the story is so loaded. The stories of Yousef and Yitzhak are never interrogated; partly because of the secrecy that shrouds their work, but also because the director doesn’t want to break the spell of that heart-racing narrative, and break the forth wall by hearing a voice from the other side of the camera questioning or disagreeing or asking for clarification. A legitimate directorial choice; but further problematic when the supporting material, the other voices, the context and statement that would give meaning or colour or challenge what is being said is not present. The film aims at stupefaction, not interrogation.

A troubling example of this is presented early within the film; Yousef, fresh off a gun charge, is flipped to working for Israeli security. Little reason is given for this, and this issue is not investigated – he states that he saw torture and death in the prison camps dominated by Hamas, and knew this was wrong. Yet the logic of the events are off; Yousef agreed to work for Shin Bet prior to being sent to the prisons, that fundamentally was why he was there on a trumped-up gun charge – to establish his credibility. Yitzhak mentions that the organisation ruthlessly exploits the weaknesses or vulnerabilities of their sources to drive them to do things they do not want to do; in Yousef’s case no follow-up questions are asked to find out how they pressured him or why pressure might have been so effective. Instead he paints himself as the sole moral man in a dirty world; and his virtue arrives fully formed and uninterrogated within the narrative. Further along, it is hinted that Yousef acts impetuously like a prince, refusing Shin Bet instructions and advice. This is not followed up; the entire dilemma that Yousef navigates every day in choosing between a cause he and his family believed in, and working for Israel causes little pause within the narrative. The tension of the lies he must tell does; indeed the focus of the film is not on the stress of that cognitive dissonance, the potential implication that he might also have considered options to get away from his handlers, but only that he was lying to his father and his people for the greater good. Something is not right here; the desire Schirman has to streamline the narrative for the audience comes very close to presenting something within the form of a lie.

This is also unsurprising; the film owes a debt to Yousef’s own autobiography Son of Hamas: A Gripping Account of Terror, Betrayal, Political Intrigue, and Unthinkable Choices. This is a book with an agenda; published in 2010 and written as Yousef sought asylum within the United States, after converting to Christianity. Yitzhak comes forward when the US government will not grant that application on the grounds Yousef had actively aided and abetted a terrorist organisation, a charge which he admits but claims that he did solely at the behest of Shin Bet. That Yitzhak would risk potential legal action and further consequences to aid Yousef is touching. The narrative earns its deep personal, humanistic resonance. But it does so at the price of something else; delivering an account in which the truth is troubling, ambiguous, and open to interpretation.

Which brings me back to my initial point. Call it an outlier of the general experience, but I walked away from this film feeling deeply discomforted. So much seemed not to be told, or elided, or edited away as complicating the narrative. Yet the film wanted to illustrate more than just a bond of friendship and loyalty; as Yousef indicates, it wants to say something about truth and reconciliation within the Middle East. That is a much more complicated narrative, even within the small frame the film adopts, and needs the hard directorial work that Schirman does not attempt but wants to lay claim to. Taking a feel-good, humanistic film like this and believing that it offers some sort of path to deeper understanding is itself deeply mistaken; the lady next to me came to the exultation of that feeling without actually putting the thought or reflection into getting there (and the film didn’t encourage it). A dangerous illusion, and one that is not going to move us forward.

Rating: Three stars.