There’s a lot of Freudian analysis to go round in Sin City: A Dame to Kill For; and as always, we’re here to provide it. A heavily stylised and occasionally entertaining film, Miller’s trademark style loses its novelty a second time round and transforms into a disturbing statement of the cultural collective unconsciousness.

Reviewed by Drew Ninnis.

Country: USA

Director: Frank Miller, Robert Rodriguez

Screenplay: Frank Miller.

Runtime: 102 minutes.

Cast: Mickey Rourke, Jessica Alba, Josh Brolin, Joseph Gordon-Levitt.

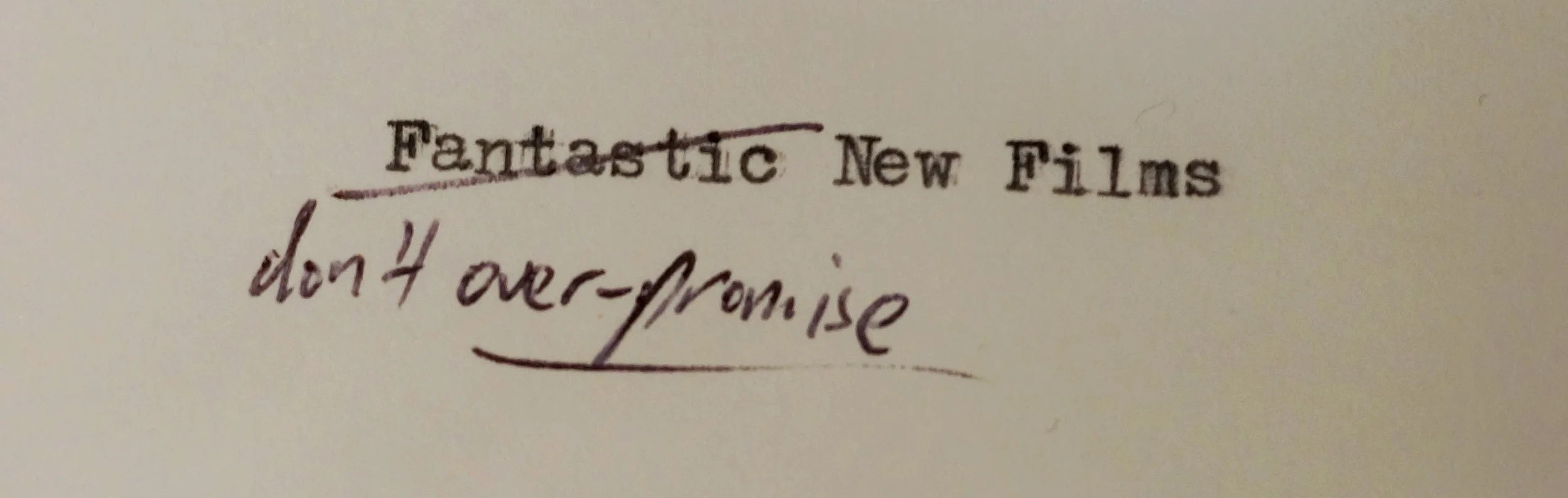

Trailer: “You keep asking for it and asking for it!” (warning: don't think we did.)

Plot: Assembled from five parts, with four loosely interlocking plots, the film follows a drunken bouncer on a killing rampage, a cocky young gambler in search of revenge, an honest gumshoe looking to save a former lover, and a stripper out to kill a crook. Some characters cross over, helping or obstructing one another, and Miller’s trademark hyper-noir meets comic style is given the full workout.

Review: ‘Women be bitches – am I right?’ screams Sin City: A Dame to Kill For from every cartoonish frame; coming down with one of the most serious cases of the Madonna-Whore complex known to man. And make no mistake; this is a film by men, for men, where the woman is a fetishised object and a seductive lure that cannot act without the hyper-neo-noir acquiescence of literally strong male characters. I’m not a gender theorist; I tend to try and stay away from such discussions as I’m not well versed in either the literature or the experience of women. But unless one switches one’s brain off before entering the theatre, questions of gender politics and the whole genre of noir can’t help but bubble to the surface. The film, in its highly stylised and ridiculously cartoonish fashion, is entertaining when it isn’t straining so hard to be über-masculine. Yet when it is, a few nagging questions nibble away at the edge of one’s consciousness – just whose damsel-in-distress fantasy is this anyway? And what role is this cultural product serving in actualising that fantasy on screen?

The narrative is not easy to follow; overstuffed with characterisations from a star-studded cast that all scream for adequate screen time befitting their fame (except for Bruce Willis, who seems content to collect a fat pay check for a day’s worth of green-screening). Plot one follows Marv (Mickey Rourke), a heavy drinker and protector of Nancy (Jessica Alba) in a town where named women need protectors, or either must hunt in gangs in an unconscious expression of what must be Miller’s dating experiences. Marv spends his time getting into other people’s fights and then forgetting how he got there; kicking off the film with a tired in media res opening. He narrates:

I don’t remember a thing. Eugh – this doesn’t look good at all; I’ve gone and done something again. Wish I could remember what … I must have forgotten to take my medicine.

Actually, I was sadly moved and started to suspect that the secret core of this sequel was a tale of one man’s moving but tragic descent into Alzheimers. Any sympathy for Merv is quickly repelled, though, as he shows less respect for police and human life than Grand Theft Auto had for Hare Krishnas. One of the five vignettes that constitute the film, entitled ‘Just Another Saturday Night,’ Merv’s rampage goes nowhere quickly – although he does show up in other plotlines to lend a helping hand.

All of these ostensibly interlocking stories are told through ubiquitous, conflicting narration – although one feels that the male protagonists should have gotten together before filming and agreed who gets to use the Batman voice. The most engaging and interesting narrative comes from ‘The Long Bad Night,’ where young gambler Johnny (Joseph Gordon Levitt) takes on the new kingpin of the franchise, Senator Roark (Powers Boothe). Johnny can’t lose with lady luck on his side; neither can Roark, who dishes out tough justice once Johnny leaves the table. Sure, another woman (this time a waitress) gets murdered in the process; but this plotline is otherwise light on the misogyny and tightly constructed, with an interesting twist. If all of the other plots in this pastiche had been similarly economical, the film may have been more successful overall. Powers Boothe is one of the most bankable and under-appreciated talents in Hollywood; taking the most ridiculous of parts and giving them a sinister charm, with a touch of class. Roark makes an appearance in another of the plotlines; an attempt by Miller to give an otherwise fragmented structure a veneer of coherence. It is not successful. Christopher Lloyd has an amusing cameo as a backstreets medic, telling Johnny ‘that’s Dr. Kroenig to you.’ Know the feeling man, know the feeling.

The other two sections – ‘A Dame to Kill For’ and ‘Nancy’s Last Dance’ – form the most problematic parts of the film. And fair warning: below I am going to possibly give away an element or two of the equally problematic film Gone Girl, so spoilers ahead.

Because ‘A Dame to Kill For’ draws on the exact same trope that has created so much controversy for Gillian Flynn and director David Fincher of Gone Girl; portraying a woman as a manipulative psychopath who uses men and sex to her own ends. So mark my surprise when a firestorm erupts over Gone Girl, but Sin City: A Dame to Kill For passes by largely unscathed. Because the message of both is that some women have power simply through the pieces they can manoeuvre around the board (usually men), and more than this that they actively gain pleasure or fulfilment out of doing so. Ava (Eva Green) is the titular damsel in distress, but one which has more to her than meets the eye. Visiting old flame Dwight McCarthy (Josh Brolin), she provokes him into a rescue attempt to save Ava from her abusive husband (Marton Csokas). Dwight is a good guy with too much honesty; therefore exactly the sort of well-meaning dupe who is going to get caught up in a dangerous game. There are bit parts for investigators played by Christopher Meloni and Jeremy Piven that are completely undercooked. Rosario Dawson (as well as a few others) turn up in the usual female ninja fantasies straight out of the imagining of The Simpson’s Comic Book Guy; complete with outfits designed by that lover of the female form George Lucas, possibly during a Project Runway unconventional challenge. Also, if you’re not intimately acquainted with Eva Green’s breasts from her entire filmography since The Dreamers, then these scenes should bring you quickly and gratuitously up to speed.

To round things out, ‘Nancy’s Last Dance’ is the usual stripper/prostitute out for revenge tale; Nancy (Jessica Alba – no one swigs from a bottle of liquor quite as unconvincingly as she does) is given many opportunities to take revenge on Senator Roark for the suicide of John Hartigan (Bruce Willis, sleepwalking), but instead loses heart, in what I’m guessing is Miller’s approximation of the insulting battered wife cliché. I got excited when Willis turned up as a ghost because I thought a The Sixth Sense crossover might be in the offing; but sadly there was not an Indian doctor or an Indian douchebag driving a car or an Indian man reading a newspaper and ruining a film to be seen (yes, yes – spoiler alert; also, Soilent Green is people). Roark engages in a bunch more misdemeanours here, making one wonder in what sort of universe an elected official can act like this with impunity; here playing Charlie Rangel, Larry Craig, and Anthony “Carlos Danger” Weiner rolled into one.

‘I know exactly where I am, I know exactly what I am’ Alba intones, disproving that mantra in numerous scenes where she has the dubious distinction of being the only stripper who doesn’t remove a single item of clothing throughout her performances. Somewhere, Gypsy Rose Lee is spinning in her grave while Bette Midler cries ‘you need something to remind you your goal was to be a great actress, not a cheap stripper!’ (It’s a reference to the movie Gypsy; yep, let’s just move on.)

So, let’s leave aside the audience cries of ‘you’re doing it wrong,’ as this plot also turns on the manipulation of Merv to do Nancy’s revenge fantasy bidding – making it a double whammy of gender stereotyping and alarmism for the film. Worse than that, we have to sit through a pretty girl cliché first, where the radiantly beautiful Nancy disfigures herself (after cutting her hair, in an act of defiance, first) in an insulting approximation of the actual, serious body issues that mostly women, mostly teenage girls are afflicted with. 'If a man did that to you I’d tear him to pieces,' ghost-Willis remarks; making me yearn for the days of really talented ghosts, like Sir Alec Guiness. Overall, it’s enough to turn a stolid, cardigan wearing, old-at-heart philosopher like myself into a marching feminist.

So, what’s going on here? Why this collective fantasy, and what receptors in the brain or pleasure centres is this film attempting to fire? Because, like in Gone Girl, it seems that focusing on the representation itself is a mistake – the better, almost genealogical question, is to ask how this fits into the broader discourse and who this serves. It’s at times like this I turn to my old friend, Robert Musil of The Man Without Qualities, for an explanation. Speaking of the public fascination with a deranged killer, Moosbrugger, who has killed a prostitute, Musil writes:

The Moosbrugger case was currently much in the news… no sooner had they [his crimes] become known than Moosbrugger’s pathological excesses were regarded as “finally something interesting for a change” by thousands of people who deplore the sensationalism of the press… While these people of course sighed over such a monstrosity, they were nevertheless more deeply preoccupied with it than with their own life’s work. Indeed, it might happenthat a punctilious department head or bank manager would say to his sleepy wife at bedtime: “What would you do now if I were a Moosbrugger?”

...

This was clearly madness, and just as clearly it was no more than a distortion of our own elements of being. Cracked and obscure it was; it somehow occurred to Ulrich that if mankind could dream as a whole, that dream would be Moosbrugger.

Husbands dream of being killing their wives before falling asleep; wives are scandalised and titillated by the danger of the newspaper report in the safe confines of their own home. The honest gumshoe and the dangerous femme fatale in need of rescue are core to the noir genre; and they are undoubtedly products of the mid-century patriarchy of the last century. But why do they still maintain their fetishistic power now? Even within shows like Mad Men or The Masters of Sex, there is a drive to display this openly taboo form of gender fetishising. The literal level to read this in relation to Sin City is that it is a revenge fantasy for the disaffected male stuck in arrested development; but, as Musil counsels, it can’t all be for Comic Book Guy. There must also be some weird, subversive thrill – a taboo – that viewers of all classes and genders have in seeing these perverse morality tales confirmed. Women be bitches, men think with their dicks, etc. Perhaps being less about holding up a mirror to society, it is more a lazy trope which is easy to follow when you’re tired and it’s date night, and you want a film that satisfies both the stereotypical his and hers requirements.

But there’s also the Freudian conception of fetish which, despite the general discrediting of psychoanalysis, I still find a sometimes useful explanation. He describes fetish as a traumatic experience sexualised in order to repeat it, over and over again, in controlled conditions – and in repeating it, coming to terms with it, finally unlocking that one combination that makes good on all the failures and erases the initial trama. Freud is quick to assert that this defence mechanism is counterproductive; the sexual repetition and charge comes to predominate and propagate itself endlessly. But if we go beyond an analysis of Hollywood that is more than just ‘sex and violence sells,’ then perhaps this is what is going on here. The movie industry in the US is famed for its left leaning sympathies; fighting for issues of gender and sexuality, for gun control and against sources of violence or oppression. Yet it unrelentingly churns out products, such as Sin City, with just those things in it – sex and violence. Could it be that this fetishisation is exactly that? A constant return to the root of the trauma to recapture it, to rewrite it, to present it as a tragic narrative and in some way redeem it. It is almost a sexualisation of politics; being unable to change the structure and normative operation of a particular network of powers, we turn to forms of representation to ‘noir-ise’ and fetishise them in order to be more comfortable, to be relieved of our powerless anemia and have the feeling of playing a classic, tragic role instead (as there is some power in this, even if we are doomed).

Under that analysis, the manipulative woman is a double recovery – an empowerment for the victim: if you’re a woman, you’re given power in highly gendered terms, in a late stage echo of Hedda Gabler; if you’re a man, you’re absolved from the hurt that bitch did to you. There’s the pleasure of judging, for both genders. But both, within that formation, are also powerless and guilty; a very Catholic position to be in. That’s where the heightened power of representation helps – being powerless and guilty is no fun, unless it’s romanticised, then seemingly there’s some grandeur to it. And in both situations there is a pleasure in the power to be found within playing that role; just as there is a perverse bite of its limitations and its oppressions. No such please arises from the bite of that oppression in real life. In a strange way, Sin City: A Dame to Kill For is simply the most recent reflection of the mythological proportions these archetypes have come to take on within contemporary culture.

Wrapping it up, what are the ethical implications to be gained from this? Well, it seems to provide a clichéd comfort and sense of importance in representing the deep, disturbing, dark emotions that sweep collectively through a culture. The ethical task is in critique; pulling apart these representations to expose the machinery of how they work. But howling against them, and manufacturing outrage, isn’t likely to get us anywhere; there will be a third Sin City. That’s like attacking the supply, instead of the demand for a particular product; better to focus our energies on the latter.

On one level Sin City: A Dame to Kill For is occasionally diverting and entertaining. On another level it’s horrifying. But overall it’s a pretty mediocre film; more of the same when the novelty has worn off. To bring that novelty back Miller could try and write a female protagonist who was truly empowered, and talked to more than just men (the film passes the Bechdel test, but only barely, through a single scene of bickering prostitutes); perhaps break out of a few of the constricting genre moulds and try deconstructing clichés instead of stylistically heightening them. Maybe add in a few guys who aren’t crooks, hustlers, or black and white bodyguards. But that’s unlikely to happen.

Rating: Two stars.