Reviewed by Drew Ninnis

Country: Ireland.

Director: John Michael McDonagh

Screenplay: John Michael McDonagh

Runtime: 100 minutes

Cast: Brendan Gleeson, Chris O'Dowd, Kelly Reilly, Aidan Gillen.

Trailer: “–Do you know what felching is? –I do know what felching is, yeah. –I had to look it up.”

Plot: Father James Lavelle is informed, during confession, of a parishioner’s intention to kill him in retribution for sexual abuse he received from another priest as a child. Calvary follows Lavelle’s subsequent week as he contends with the sins of his flock, and the looming confrontation the following Sunday when he may be killed.

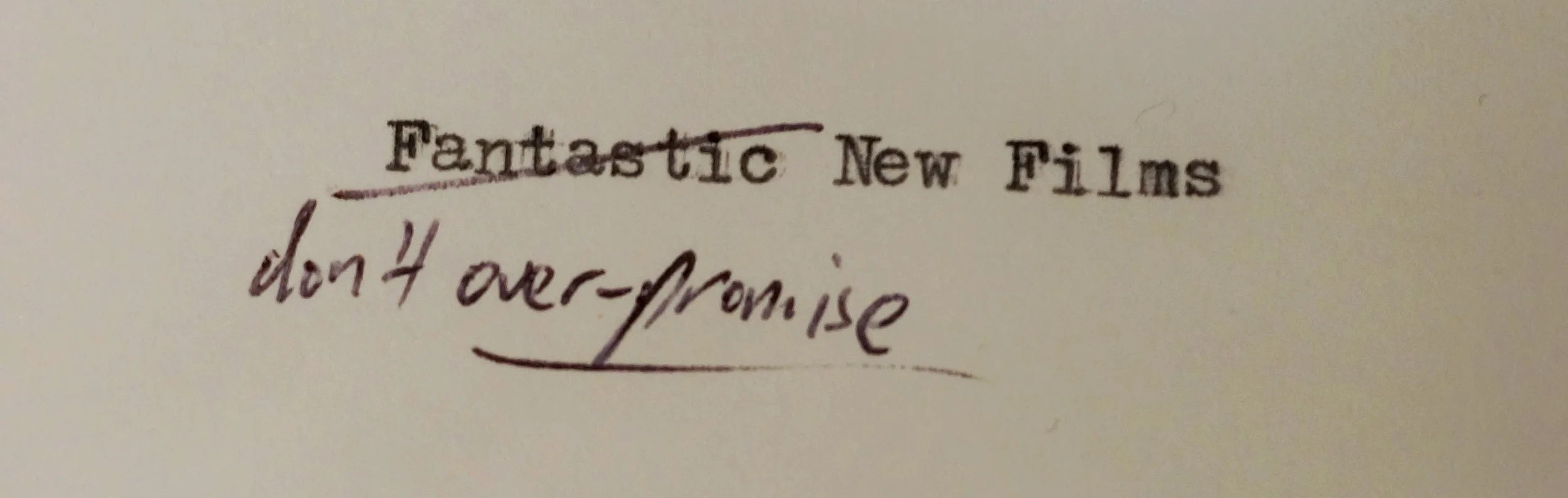

Review: In its opening scene, Calvary writes a pretty big cheque that defines the shape of the film to follow:

Father James: What do you want to say to me? I'm here to listen to whatever you have to say.

Man’s Voice: I'm going to kill you, Father.

Father James: Certainly a startling opening line.

Man’s Voice: Is that supposed to be irony, Father?

Father James: You're right, sorry. Let’s start again.

Built into that opening is the promise of a dark, corrosive wit; and a sudden, startling humanity. It’s a promise that the film delivers on, and then some. Calvary is an exceptional film, a powerful dialogue conducted through the bravura performance of Brendan Gleeson; and one which balances philosophical contemplation, religious allegory, and existential dilemma with smart humour. One character remarks to Lavelle ‘that's what I've always liked about you, Father; you're just a little too sharp for this parish.’ The same could be said of McDonagh’s excellent film, which crams into 100 minutes enough sophisticated thought to challenge audiences for the rest of the year. That much becomes evident on hearing audiences leaving the theatre; where different readings of the film abounded, but were in agreement on the fact it was an excellent film.

For me, two elements loom over the film – the first being the timeframe of the film. Lavelle is confronted during confessional on Sunday and informed that his assailant will meet him on the beach in a week’s time, stating ‘killing a priest on a Sunday, now that’s something.’ It soon becomes apparent that Lavelle has grimly agreed to keep the appointment; as he reveals to the Diocese’s bishop, he knows the man who has threatened him. This puts a clock on the action, and neatly structures the film into a tight narrative of eight days (two Sundays). The temptation of the audience is then to play whodunit (future tense edition) upon meeting a new member of the village; but to the great credit of the film, this is quickly forgotten as it becomes apparent there are deeper problems in this community and the interest created through excellent characterisations takes over.

On the same Sunday as the threat, Lavelle’s colleague remarks on the ‘things you hear in confession these days. The mess people make of their lives.’ This rings true as Lavelle continues with his pastoral duties, contending with a rogue’s gallery of sin. Discussing the details of each would dilute the pleasure of encountering each one by one, and the surprise of discovering what lies beneath each. Lavelle’s response to the progressive escalation of bad behaviour is one of composure and just-too-sharp wit; knowing exactly how to deal with each personality with a minimum of harm. That too seems to be the game that Lavelle’s vocation has reduced him too; not perhaps actively helping anymore – many of the parishioners seem beyond help, and not asking for it – but minimising harm. Each performance is excellent, but shaded by the positive misfortune of being eclipsed by the stellar performance of Gleeson himself. All of the best lines, at least at the outset, are reserved for him.

As Sunday approaches, Lavelle must reckon with his choices – a reckoning complicated by the chaos that has seeped into what seemed a clear decision at the outset of the film. One of these elements is the arrival of his daughter, Kelly – a relic from his past, married life and a hint at the origins of his vocation.

Part of the reason for the many readings of this film is the many layers of allegory the film chooses to indulge in; a reflection, perhaps of the role of the Sunday sermon in Irish-Catholic church and how the mutability of those words allow them to be used for many different purposes. Calvary is the place outside Jerusalem where Christ was said to be crucified, in Matthew 27.33 ‘a place called Golgotha, that is to say, a place of a skull.’ Whereas the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem is associated with the burial and resurrection of Jesus, Calvary is associated only with crime, injustice, death. A dying captain in Shakespeare’s Macbeth remarks:

As cannons overcharged with double cracks,

So they doubly redoubled strokes upon the foe.

Except they meant to bathe in reeking wounds

Or memorize another Golgotha,

I cannot tell—

But I am faint, my gashes cry for help.

In Calvary, the allegory is a double-edged sword; of Christ’s death, but also a place where men extract vengeance in blood. The tension between forgiveness and vengeance is skilfully maintained throughout the film; and is embodied in the choices that Lavelle must make.

Calvary also lends itself to a reading of the titular unholy crime as that of sexual abuse; the driver of the story, but one that is further elided as the film progresses and is only mentioned in passing throughout the body of the film. It is undoubtedly an important reading of the film, a directly intended one; but one that tends to hide the other allegories in which the film speaks. The genius of the script and direction is that there is no right or wrong reading here, just a skilful layering of allegory and metaphor.

In parallel to this is the community itself, which seems sunken in a traditional conception of sin and has little use for the church, except as a hollow ritual. Lavelle remarks that he believes there has been far too much emphasis on the sins, and not enough emphasis on the virtues – many of which his character embodies. Each villager seems to loosely embody one of the seven deadly sins – lust, gluttony, greed, sloth, wrath, envy, pride. A montage near the end of the film seems to support this reading; yet this is treated lightly, and the film doesn’t overemphasise these fallibilities. In this light, Lavelle’s struggle is painted as one against the dark and implacable forces at the core of human nature; where being a priest is no immunity. Lavelle himself confronts his fellow priest as embodying a vocational sloth, and having no passion for good works or works of any kind.

Finally, it is hard not to read Lavelle’s plight as a retelling of the Book of Job; indeed, several of the misfortunes that are visited upon Job seem visited on Lavelle in altered form. On one level Calvary is a story of one man’s faith tested to extremes, skilfully retold in a naturalistic manner. Ultimately, Job ‘cursed his day’ of birth and asks ‘Why died I not from the womb? Why did I not perish at birth?’ The cry is an old one. In his Birth of Tragedy, Nietzsche cites a pagan echo in the myth of Silenus, the satyr and companion to Dionysus, who says:

Ephemeral wretch, begotten by accident and toil, why do you force me to tell you what it would be your greatest boon not to hear? What would be best for you is quite beyond your reach: not to have been born, not to be, to be nothing. But the second best is to die soon.

It is a question that many characters seem to refer to within the narrative; none more so than Father Lavelle, who must confront not only existence as a man but also existence as a priest.

This is where I think the second element that predominates the film comes in; that of the landscape itself, particularly the numerous shots of Benbulben (a rock formation, part of the Dartry Mountains) that loom over the action of the film. The landscape is harsh and pagan; full of savage forces and spirits, as well as home to a megalithic cemetery. The behaviour of the townsfolk mirrors a slide or reversion into a native paganism; where Lavelle’s civilising mission as the good priest seems doomed to failure, contending as it does against the stones themselves.

My reading of Calvary is that this is the fundamental paradox at the heart of the film; that the Catholic Church as an institution, and Lavelle as its emissary, forms the cornerstone of Irish civilisation. And that, like all civilisations, this mission is built on blood and great crimes. In his Critique of Violence, Walter Benjamin points to the fundamental paradox of violence and order – that any form of sovereign order, which excludes violence and guarantees right, must itself always be founded on an act of violence. Given this lie at the heart of order, he further points out that any order will be vulnerable to further acts of violence, generating the unmistakable cycle of history.

Lavelle confronts this paradox in its most personal, existential form; it is the destination of that Sunday the film inexorably moves him towards. Can he remain part of an order that brings many meaning and elevates, despite the blood on its hands? Or in renouncing this, does he hand himself over to another, wilder form of violence?

Ultimately, this is over-analysing what is an outstanding film; one that manages to pack so many provocative thoughts in with such humour, in a manner as graceful as their unpacking in this review has been ungraceful. Few films compel viewers to such lengths of sermonising on the possibility of their reading; and that is a testament to the strength of the film. As Father James Lavelle puts it, ‘My time will never be gone.’

Rating: Four and a half stars.