Reviewed by Drew Ninnis.

Country: Australia

Director: Rolf de Heer

Screenplay: David Gulpilil, Rolf de Heer.

Runtime: 108 minutes

Cast: David Gulpilil, Peter Djigirr, Bobby Bunungurr, Peter Minygululu.

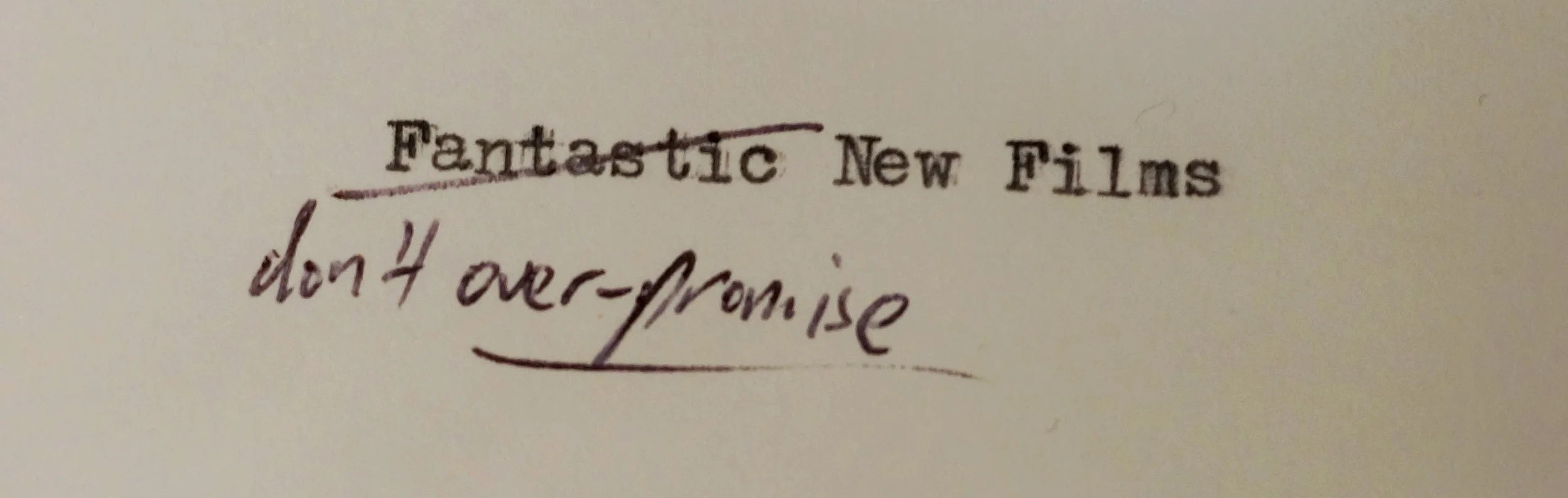

Trailer: “To live the old way.”

Plot: Set during the Australian Government’s full-scale intervention into the indigenous communities of the Northern Territory,Charlie’s Country follows the Charlie of the title as he struggles to reconcile his way of living in the bush with the new regime. With heavier enforcement of longstanding but ignored laws, Charlie’s friends lose their car and hunting weapons; struggling to subsist on the allowance the government gives them.

Review: Rolf de Heer’s Charlie’s Country is a deeply humane film that opens up an entire cultural horizon to audiences, delicately tracing the fate of a broken civilisation – that of the indigenous Australians. Many viewers will approach the film Charlie’s Country with trepidation, as it treats a deeply sensitive topic in Australian politics; the hesitant will likely include reluctant Australians who are wary of these issues, and foreign audiences who may not be familiar with them. On both counts audiences should rest at ease; although Charlie’s Country does implicitly explore these issues, it does so through the poetic portrayal of the existence of one character – Charlie, played by David Gulpilil in what must now rank as one of the greatest Australian performances on screen – and a local Aboriginal community in the Northern Territory. What emerges is a portrait in miniature of an entire world and the quiet, gentle man who occupies it; and alongside that portrayal, de Heer must be praised for his picturesque but honest portrayal of the Australian outback. Exploring the mode of being that Charlie inhabits is key to the more political elements of the film; vividly demonstrating how these structures clash with a form of the law and society that is fundamentally unable to accommodate them.

That the Aboriginal people constitute one of the oldest civilisations on the planet is without contest, though frequently forgotten; arriving in Australia at least 50, 000 years ago and maintaining one of the oldest continuous cultures known. Recent archaeological evidence indicates that even before European discovery and settlement of Australia, these indigenous peoples traded with the Chinese. Indigenous Australians were traditionally a nomadic people who lived off the land and the bush; a practice beautifully and sensitively illustrated in Charlie’s Country, as Charlie disaffected with the rule of law within the town retreats to the bush to subsist and to be at home. In the wake of the Little Children Are Sacred (‘Ampe Akelyernemane Meke Mekarle’) report in 2007 which identified numerous health and social problems within Aboriginal communities, the then Howard Government embarked on a controversial intervention into these communities which increased police and social worker presence, also implemented income management programs and tighter restrictions within indigenous communities in the Northern Territory.

This forms the background of Charlie’s Country, and far from inviting immediate judgement from an ideological position, the film encourages audiences to suspend opinion and engage in understanding the terms of Charlie’s existence. It is a far from ideal one, as Charlie inhabits a lean-to on the edge of the community, as his extended family occupy and crowd out their house. Every week, the community’s welfare checks are paid out in cash, which Charlie immediately and casually shares with his fellow members. It strikes me that even my language is inadequate in attempting to describe the relationship this community has to each individual; we would say friends, families, fellow members, neighbours, colleagues yet none of these properly describe the fabric of Charlie’s community. That the film conveys these relationships effortlessly, in a way beyond common words, marks it as exceptional.

But Charlie’s generosity quickly lands him in hunger and deprivation, and he falls afoul of new laws that are being enforced within the communities – depriving him of his means to hunt, or to eat. Fed up with the terms on which he must exist in town, Charlie retreats to the bush and the film enters a meditative space in closely portraying his life there. I was moved and envious, wishing to experience the calm the film expertly documents. It is easy to romanticise a fictional state of nature; but in this case I was convinced that this was neither fictional in its truth nor romanticised in its resonance as Gulpilil and his character occupy the landscape so convincingly. Yet even in its most compelling section, the film is deft enough to acknowledge that this perfect state cannot last for long; and Charlie’s age and health are quick to catch up with him, occasioning his removal to a Darwin hospital.

The sections of the film in and about Darwin are likely to be the most objectionable to some viewers, if they are looking for reasons to object – and the film does not flinch from portraying the corrosive influence that alcohol has in indigenous communities. But the film also, to my mind, maintains its humanity and its equilibrium in doing justice to all parties – the well intentioned but inadequate systems meant to protect indigenous populations, and the impacts of these paternalistic initiates on the individuals themselves. And there is still much poetry to be found in the city – as Charlie remarks to a terminally ill friend that if he goes to hospital in Darwin he will ‘die in the wrong place.’ The same fate tragically threatens Charlie; and upon encountering his own friend within the hospital, he makes a fateful decision to leave and be home.

In 2008 our then Prime Minister, Kevin Rudd, apologised to Aboriginal Australians for the historic crimes committed against them, including the ‘Stolen Generation’ who were taken from their families and settled with white foster parents. These were significant words, but still words – and a debate continues within Australia of how to integrate this neglected civilisation within our current social and political systems. In recent weeks, indigenous leaders Noel Pearson and Nova Peris have disagreed on the key issue of Aboriginal income management, indicating that there is a long way to go and no easy answers in facing up to the responsibilities we owe our ancient brethren. But Charlie’s Country is a powerful reminder of who we must forge a relationship with; and it is sad that it might merely be interpreted as a political statement, rather than an acknowledgement of something deeper, to say that after viewing the film I cannot help but agree with its title.

Rating: Four and a half stars.