Reviewed by Drew Ninnis.

Country: USA

Director: Lasse Hallström

Screenplay: Stephen Knight. Novel by Richard C. Morais.

Runtime: 122 minutes.

Cast: Helen Mirren, Om Puri, Manish Dayal, Charlotte Le Bon.

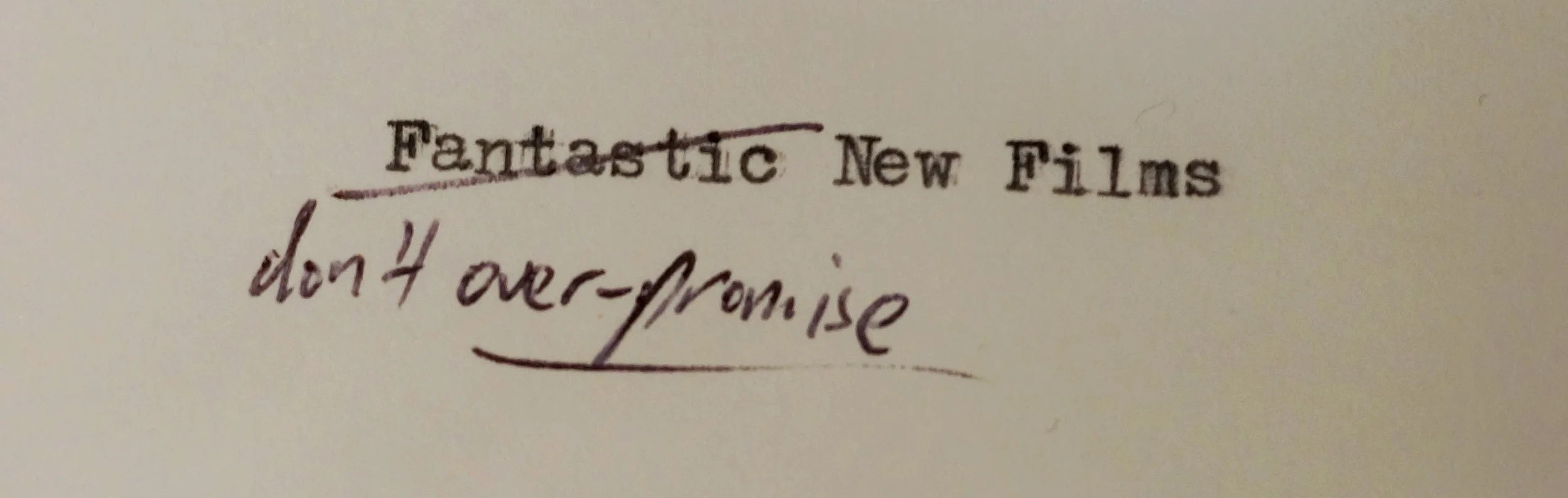

Trailer: “It is a passionate affair.” (warning: unlikely.)

Plot: Driven from their successful restaurant and home in India, the Kaddam family find themselves stranded in a small town in France. Setting up shop across from a Michelin starred French restaurant, they proceed to disrupt the cultural prejudices of the locals with great success. But son Hassan wants more, and embarks on a quest to conquer French cuisine with the help of former rival restaurateur Madame Mallory.

Review: The title of the film The Hundred-Foot Journey is telling, as it refers to the hundred feet between the kitchens of rival restaurants – a Michelin starred, fine dining establishment that is favoured by French ministers, and the upstart Indian restaurant of the Kaddams which uses the secret spices of home. That is the only distance which is of importance to this film; which might be described as exploitative if it weren’t so naïvely post-post-colonial.

Although they are mundanely documented in the opening half of the film, the many thousands of miles the Kaddam family have travelled and the tragedies they have endured are of no importance to the core of narrative; what is important is the graduation of an exotic, innovative enfant terrible into the refined halls of French cuisine. That explains why, for the purposes of the film, the Kaddams are only Indian in as far as their food and their skin – any other factor would complicate a clockwork narrative which has no interest in difficulties outside those contrived in the third act. However, what the film represents is something rather more sinister; a slow homogenisation of difference, which adopts the motherhood statement of equality in the name of resurgent, post-globalisation capitalism. Refinement and worth, under the terms of films like The Hundred-Foot Journey, are not the appreciation of a culture but its integration into consumption. Michelin stars matter; the embarrassingly patchy description of the riots that drove the Kaddams to where they are in the first place do not.

And consumption is key; the film itself is pornography for the elderly, having lost their libido but replaced their teeth. There are long, lingering shots of refined French food; the sauces, the preparations. They become veritable landscapes within the shot. The Indian food, interestingly, is only ever shown in passing and as a prop – unless it is a shot of the Kaddam’s earthy, homely spices and their quaintly labelled jars. That is appropriate, as Indian exoticism seems to be having its moment as a suitable marketing hook to draw in aging audiences – in the wake of Slumdog Millionaire, The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel (now to have a sequel, I found out during the trailers, oh joy), and the much better but similarly marketed The Lunchbox, among others. With the snooty French hook, and a geriatric Beatrice and Benedict angle between the aged proprietors, I’m sure the producers thought they couldn’t miss (and if box office takings are the measure, they haven’t).

The recipe itself is tried and tested. Émigré family flees from violence at home, hilariously recounted to a poor customs officer just trying to do his job and inquiring why they wish to enter Europe. Told in flashback and with narration by Hassan, the tale would be funny in its sketchiness (they fled because a politician won an election, and some people were not happy, burning down their restaurant where he happened to be dining – no follow-up questions, please) if it weren’t a bald-faced insult to actual asylum seekers. The script demands the mother must die in the fire – to create pathos for Hassan (Manish Dayal), and a love interest for his father (Om Puri). Every old ethnic joke is trotted out along their way to France (‘he looks like a terrorist!’ Papa declares; also, their music is loud, and so is their strange clothing); and finally arriving by accident at their future home, where Hassan is enchanted by local apprentice chef Marguerite (Charlotte Le Bon – with eyes wider than Anne Hathaway’s, I did not think that possible). They pick mushrooms by the moonlight, he reveals his talent at a romantic picnic, she provides a vital piece of information on the stupid test of Madame’s he must pass, they hit the usual bumps in the road and compete, before finally reconciling with some suggested, tasteless makeup sex on top of the ingredients they are probably serving later. Enmity between the elderly turns to tasteful toasts of exquisite vintages, talk of girlfriends and dancing, and all is well.

Of course the latter half of the plot centres on Hassan leaving his family to pursue his fortune in Paris as a top chef – joining a restaurant that must have been conjured from Heston Blumenthal’s nightmares – where he makes a splash and gets them moving towards their third star. But, feeling burnt out, he sits one night with a fellow Indian and janitor for that turning point where the fool’s wisdom is delivered, an epiphany arrives on time (through a shared, traditional dinner baked by the mandatory menial’s wife; shame he was probably only talented at neurosurgery back in his home country, and so had to become a cleaner) and Hassan heads back to his roots. Oh, no – not back to India, his culture, his people, or even to a place within France where he can be part of a community and celebrate their religious festivals or partake in a slice of home – no, back to Madame Mallory’s fancy French kitchen.

And the colonial fringes continue to empty out or be exorcised; and consumptive capitalism continues to call all to the centre. Literalised here as a tale of food and difference; where traditions are best left uninterrogated, as we all drift towards the cultural mean. Where asserting your identity is only as effective as the success of your enterprise (a battle of businesses, of course, settles the respective worth of your cultures – the consumer decides). Outside of the cinema unchallenged hordes of ubiquitous white empty their pockets and condescend to the rest of the world, which will outlast them, with an ‘oh, and it has Helen Mirren in it, she’s very good, I like her.’ She has certainly come a long way from The Cook, the Thief, His Wife, & Her Lover; nowadays, the plat de résistance of consumption is unironic.

Rating: One and a half stars.