Reviewed by Drew Ninnis.

Country: USA

Director: Richard Linklater

Screenplay: Richard Linklater

Runtime: 165 minutes.

Cast: Ellar Coltrane, Patricia Arquette, Ethan Hawke, Lorelei Linklater.

Trailer: “Life doesn't give you bumpers.”

Plot: Filmed over twelve years, Richard Linklater’s Boyhood follows the childhood and adolescence of Mason as he develops into a young man and confronts the common growing pains of the American male. But Boyhood is also a portrait of his dutiful but lonely mother, and his absent father; as well as his sister Samantha. Documenting the milestones, birthdays, separations, births, ups, and downs of ordinary life, with Mason and his sister eventually leaving for college and embarking on their adult lives.

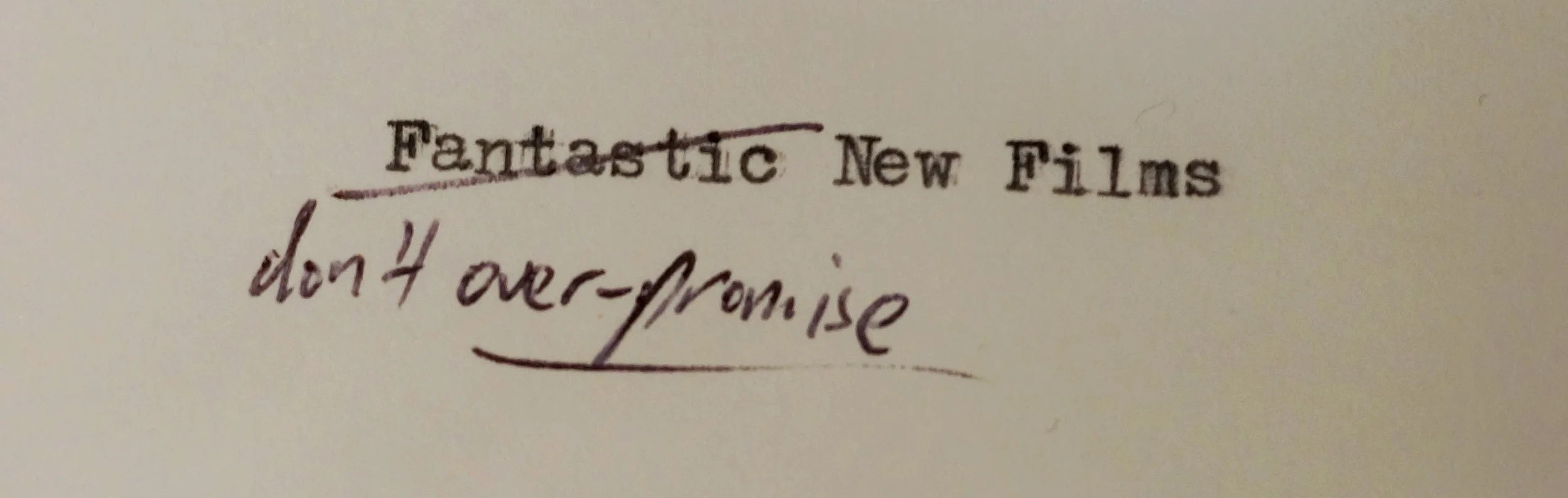

Review: Richard Linklater’s Boyhood has already been enshrined as an unlikely success story, and a remarkable cinema accomplishment. That it is; but whenever a film of the moment is fated as a masterpiece, audiences develop an understandable reluctance to engage with it – perhaps feeling, in the old-style Bergman or Tarkovsky school, that being a masterpiece means hard work for the viewer. No so for Boyhood, which is intensely enjoyable and moving, authentic and yet entertaining; many will look at the length of the film and be put off, not realising that the time so quickly and pleasurably disappears. The film proves that even the most well-trodden, ordinary, familiar material can be fascinating and enjoyable in the hands of a very talented director and a great cast. Richard Linklater is undoubtedly a very talented director; and over the length of Boyhood, the cast prove they are equally as gifted.

Filmed at the rate of a week each year for twelve years (from 2002 to 2013), the plot of Boyhood is full of incident but in itself unexceptional. That’s a compliment, because Linklater has a talent for locating the deeply moving and meaningful within experiences or events that we haven’t just seen before but have likely experienced many times ourselves. For me, that was the most joyful, most confronting and awkward part of the first half of the film – recognising so many of those moments, squirming as Linklater and his cast nails them, then feeling relieved and buoyant as the film moves on and we move on with it. What the film communicates is that our pasts are important, actively demonstrating that there are some moments you’ll forget until a film or moments like this remind you of them, and the pleasure of contemplating them from a different place, almost as a different person. But in a strange way, they are also pasts plural – many iterations of the self that we experience, come to terms with, cast off, and re-adapt to new lives or new situations. Mason’s mother, Olivia (Patricia Arquette), quietly illustrates this while moving on from one absent ex-husband to a new life, studies, and eventually a new family. Not everything turns out well, and the character has a knack of finding men who are dangerous for her; but at the same time, one cannot point to the same mistake, just the same misfortune. Mason (Ellar Coltrane) and sister Samantha (Lorelei Linklater) are spectators to their parent’s choices, unexpected beneficiaries or victims but also individuals in their own right attempting to carve out a space for themselves in their slowly expanding worlds.

Although the film is primarily concerned with ‘boyhood,’ one of its chief accomplishments is to encourage its audience to re-evaluate their own childhood experiences from the lofty vantage point of adulthood. A key scene comes when their absent father (Ethan Hawke) returns from working a trawler in Alaska and demands to be a part of his family’s lives again. The routine will be familiar to many children of divorce – taking them bowling, for icecream, trying to win back their affections with gifts and insisting on staying behind after visiting hours are over to surprise their mother. The resulting argument between the two adults, viewed from the window by their kids, is heart-breakingly familiar. Yet this time around, I couldn’t help but have sympathy for mother Olivia for the sacrifices she’s made day in, day out; and her anger at the fickle behaviour of her ex (worried that he will disappear again), who now wants his own place within the family acknowledged by virtue suddenly wanting it. The childhood experience of a mother, ruining the fun, being unfair transforms into that deep, sad adult understanding of the fragility of relationships and the sacrifices a single parent can make for their child.

Despite tackling common topics, Linklater is smart in avoiding cliché. Their father, for instance, does stick around and does improve his act – going on to a successful marriage, another child, and becoming a pillar of support from his family. If Arquette’s performance is stoic and moving, Hawke’s performance is lighter and funnier even as it remains as moving. The two performances counterpoint each other throughout the film, demonstrating that this is a story not just of two children, but all of their family members. Coltrane and Linklater start out as talented child actors, and slowly develop into talented teenage performers, although not without a few bumps and missteps. But ultimately all is forgiven by the authentic whole the film creates, crafting a coming-of-age story that has effectively made any other American coming-of-age film redundant. Linklater’s accomplishment isn’t completely unique – as the concept seems to be inspired by the Seven Up series of documentaries, which are also deeply moving – but it is significant and required viewing for cinephiles everywhere. Yet again, this has the unfortunate side-effect of putting off casual cinema-goers, and it shouldn’t – true to his style as a director, Linklater’s Boyhood always remains approachable, emotionally true, and above all entertaining.

A final pleasure, among many in the film, is watching Linklater’s directorial style develop - and here he seems to undergo the stylistic equivalent of a Benjamin Button. Starting out as a polished director, and focused on bright (sometimes overstuffed) compositions with subtle but steady movements of frame and camera work, Linklater slowly becomes more and more stipped down. Towards the later scenes, the filming is workman-like and static; focusing intensely on the interactions within the scene and the relationships of the actors, showing deep confidence in the quality of his performers and the simplicity of his script. It all pays off; delivering great performances, a remarkable film, and demonstrating a directorial talent that has been justifiably praised and reappraised. Don’t hesitate, go see Boyhood. You’ll have so many personal, intimate reactions to the film that you’ll be desperate to discuss them with family and friends afterwards.

Rating: Four and a half stars.