Reviewed by Drew Ninnis.

Country: Australia

Director: Matthew Saville

Screenplay: Joel Edgerton

Runtime: 105 minutes.

Cast: Tom Wilkinson, Joel Edgerton, Jai Courtney, Sarah Roberts.

Trailer: “You didn't mean to do anything bad.”

Plot: Driving home drunk from a police function, Detective Malcolm Toohey knocks a child off his bike and causes serious injury. Covering up his role in the affair, Malcolm is aided by veteran police investigator Carl Summer, because he is ‘one of us.’ But fellow detective Jim Melic is uncomfortable, and Malcolm’s guilt begins to consume him as he gets to know the family of the victim and is hailed by the media as a hero. When their story begins to unravel, Jim and Malcolm have second thoughts – leading to an inevitable confrontation with Carl.

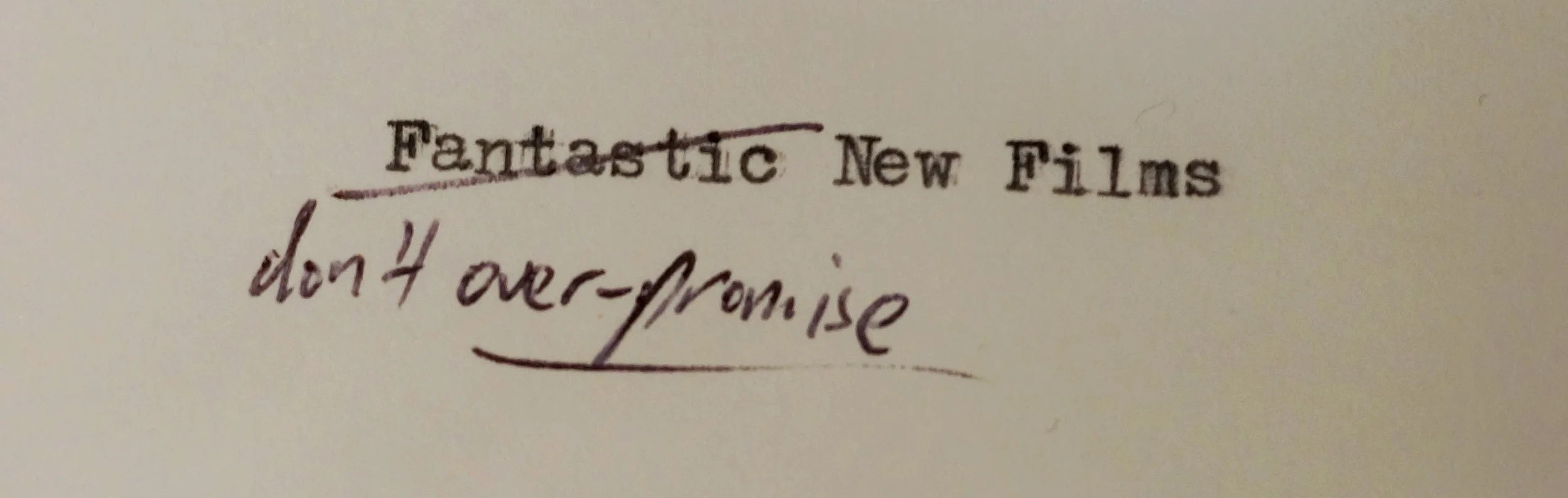

Review: Much has been made of the lengths to which actor-writer Joel Edgerton went to produce the script for the latest Australian crime thriller Felony – interviewing current and past police officers and, by his account, conducting extensive research to present something original and authentic to audiences. Chalk it all up to marketing, because what Felony does end up offering is a standard Australian crime drama that would be more at home on a local T.V. channel than in cinemas. Let’s leave aside the issue that the concept of a ‘felony’ no longer exists in Australian law (they are now ‘serious indictable offences’ or criminal acts depending on your jurisdiction), making the title an easy misnomer meant for the international market. The film is disappointing because all the elements are present for something better and the setup for the core tension of the film is solid. But Edgerton’s script, at a certain point, runs out of ideas of what it wants to do with these elements and reverts to a soapy melodrama that becomes increasingly unconvincing. At the close of the film we are left with a series of tragic, loosely related events that ratchet up the emotion but lose all meaning in the process. It smacks of the director and writer putting their thumbs on the scale to deliver a differential punishment that is more deus ex machina than logically flowing from events to that point.

Not so in the beginning. After a clever credits sequence, we open on a raid in progress by detective-in-charge Malcolm Toohey on drug lab. Taking 'two shots for his trouble,' but not discharging his weapon, we are left in no doubt that Malcolm is a good bloke and a talented officer – sentiments reiterated by his boss at a piss-up (read: traditional Australian celebratory drinking) that evening. This leads into the low-level police privilege element of the storyline, with Malcolm driving home drunk with the help of his colleagues (who give him a password to get through a roadside breath test without trouble). Five blocks from home, Malcolm knocks a local child from his bike and stops to find the kid on the ground, unconscious. Doing the right thing, he calls an ambulance but immediately starts to prevaricate and then openly lie about his role in the accident, with the unquestioning indulgence of his fellow officers.

The accident itself presents the first problem with the film. It is delicately stage managed to cause an incident to drive the further plot; but tries not to lose audience sympathy for Malcolm, who is obviously in the wrong. Although it is never addressed, the child suffers from something akin to the ‘eggshell skull’ case where what seems like a not too bad fall gives him serious brain damage and sends him into a coma (one of the several credulity stretching plot points of the film). The effect the script tries to generate is that of the broadest Greek tragedy, with the fates conspiring against Malcolm for this one understandable slip and his resulting guilt. The problem is that it isn’t understandable, in fact it is reprehensible in this day and age – and the script attempts to deftly dance around this issue by nibbling at the edge of good guy Malcolm’s culpability, setting up Carl (Tom Wilkinson) as the lightning rod of blame; an attempt that seems artificial at best. Of course the script follows up the incident with plenty of family shots of the good father and a guilty visit to the hospital, as well as establishing Malcolm’s talent at work, to build up his bona fides with the audience. I was left unconvinced, as to me it came off as amateurish and manipulative; but not so, it seems, with other easily hoodwinked critics.

The resulting fallout offers tantalising hints of interesting directions that the film could have pursued, but fails to deliver. The narrative of our tragic hero is intercut with the unrelated investigation that Carl and his junior detective Jim Melic (Jai Courtney) are pursuing into the death of a young girl and the possible involvement of a sex offender. This is where Wilkinson’s performance comes into its own, as he relates his sense of justice within the case from his gut and is furious with the bureaucracy and the courts, calling the latter ‘the biggest criminal of all, the court system.’ Wilkinson has been justifiably praised for his performance here – going full bore with an ex-pat’s acquired Australian accent – and giving gravitas and grounding to the more florid lines of an otherwise viscerally banal script, lamenting ‘time and the world swallows events, and it’s sad, but that’s what it is.’ It’s a nice counterpoint to the script’s general trafficking in mediocre drama Australianisms like ‘Stop it, I’m on ya mate!’ There was a great concept to be run-down here, particularly the crusader’s sense of justice that animates the sense of purpose these characters hold to and need, and how they despise the arms-length, objective checks-and-balances approach of the courts. However, aside from a scene of Wilkinson drinking on duty this is not followed up, frittering away a potentially powerful path for the film.

The other performances are varied. Melissa George does her best with the stereotypical wife role of a cut-rate Lady Macbeth, telling Malcolm that ‘we can live with this’ when he confesses his guilt, and is otherwise is simply required to stand to the side wide eyed and open lipped. Courtney is less compelling, not quite channelling a crack investigator but more a local meathead at the Rugby club, and is done no favours by a script that has him attempting an ill-conceived final quarter romance with the victim’s mother that is predictably badly received.

The most puzzling element of this is Edgerton himself, who is provided with the opportunity to write the perfect part for himself; but instead chooses to portray a blank, unconvincing front of masculinity that passes for the cliché of the Australian male. Limited to blokey interactions, like asking a colleague ‘how’d you pull up’ from a night of drinking, Edgerton’s emotional range is shown off in overplayed scenes where he confesses his inner turmoil with an ‘I did it’ in a gruff Batman voice. Of course this takes place in a textbook scene of the wife discovering the husband in the lounge, drinking in the dark. Minimalist, authentic Hemmingway-esque dialogue works best when there is something to read off the character’s faces and the subtle complexity of the interactions they are thrown into; given a chance to write and deliver both ends of that equation, Edgerton falters and pushes out a relentlessly two dimensional performance. That flatness exacerbates the unearned melodrama that demolishes the credibility of the film in the last twenty minutes.

Similarly, Saville’s direction can only be described as ambitious but falling short of the mark. There’s a touch of lens flare and plenty of furtive meetings filmed at night in a dark Michael Bay palette (black backgrounds drowned in a street-lit orange) that attempts to appeal to the vocabulary of the filmic thriller, but this proves to be a case of style over substance. Indeed, it leads to the amusing non-sequitur of Malcolm receiving a call in broad daylight and after a ‘where are you right now? I’ll be there’ meeting request, turning up to a scene that is shot in the dead of night before a half-visible Sydney Harbour Bridge. Other directorial choices recommit the sins of their Home and Away origins, with lingering shots of photo frames to create pathos; emotionally significant news being delivered to a montage of characters who all happen to be watching the T.V. at the same time; and a shot of a garage door closing behind Edgerton’s character, presumably meant to mirror his increasingly trapped psychological state, that Seville likes so much he returns to it again and again. Less symbolically inclined audience members will wonder what’s with his fascination at electric doors and cars parking in carports.

‘You’re the guy nobody likes, you’re the guy in the band who’s always complaining,’ Wilkinson cautions Edgerton’s character with at the midpoint of the film, clarifying that if a band member writes a shitty song, they all play it. ‘You’re the guy who ends up going solo,’ he concludes. Felony sets itself up with many pretensions – from exploring guilt and a literal blood-soaked appeal for forgiveness, to the criminal slippery-slope of brotherhood and group-think, and the concepts of justice and vigilantism. Finding nothing new to say about these things, it retreats into a tried and tested formula of the police drama genre. You’ll have seen this before, you’ll have seen it done better. This leaves the film in the position of being less like a shitty song from a great band, and more like those solo careers that are a shadow of some other greatness. Not a great opening move from a writer and a director who are at the start of their film careers, not their end.

Rating: Two and a half stars.