Reviewed by Drew Ninnis.

Country: United Kingdom

Director: Steven Knight

Screenplay: Steven Knight

Runtime: 85 minutes.

Cast: Tom Hardy, Olivia Colman, Ruth Wilson, Andrew Scott.

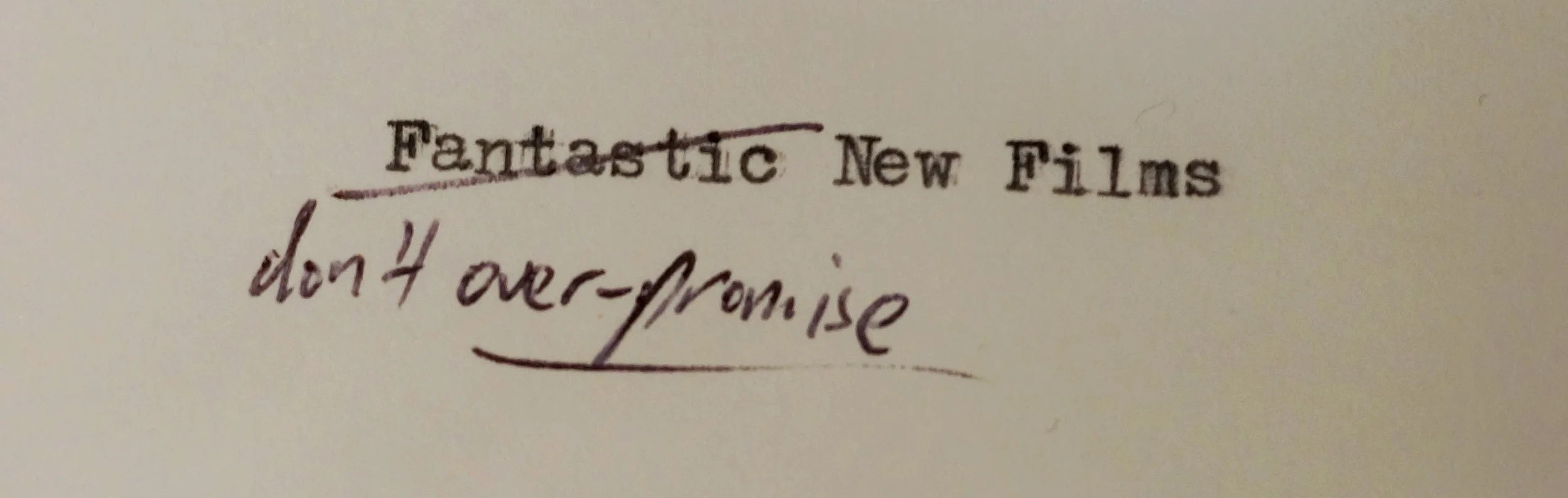

Trailer: 'You make one little mistake.' (warning: another supremely misleading trailer.)

Plot: Dutiful, dull Ivan Locke leaves a construction site with the intention of driving straight to London within two hours. His reasons for this are initially opaque, as he handles a series of crises at home, in a hospital, and back at the site through no medium other than his mobile phone. What emerges is a picture of a man in conflict with his dead father, the life he has carefully built for himself, and a single mistake which may tear it all apart.

Play along at home: In short, Tom Hardy drives around all night, arguing with his rear view mirror and doing a bad Anthony Hopkins impression. The results are unsurprisingly dull. Director Stephen Knight could re-shoot the whole thing with Hardy's rendition of Bane instead, making the film instantly more gripping. Once you've read the following review, try reading it again but replacing every reference to 'Ivan Locke' or 'Locke' with 'Bane.' See? That film would have been fucking amazing.

Review: Locke is meant to fulfil two purposes – attempting to act as an audacious directorial debut for longtime script writer Steven Knight, and to provide popular actor Tom Hardy with a literal starring vehicle. On paper, the film looks certain to be an unusual hit – filmed in or around the car titular character Ivan Locke drives determinedly for the hour and a half length of the film, negotiating a carefully constructed life and career in collapse while arguing with his dead father in the rear view mirror. Hardy’s presence accounts for its large and mainstream cinema release, despite being more likely to be an indie darling. Yet for all of its conceptual daring, the end result is a drab little film and after a half hour or so, surprisingly boring.

The reasons for this can be found in the two main elements cited above. Having an individual navigate a crisis while in a confined space and on a mission is hardly a new twist to the bottle movie; quite the contrary, as a car has been used for this exact purpose as recently as David Cronenberg’s Cosmopolis. The script is wisely as far from that commentary on American decline as possible; focusing instead on the small-scale drama of Ivan Locke as he drives to London to assist with the birth of his illegitimate child, the product of one fatal night of pity and drunken passion (with Olivia Colman). Coincidentally, he is also stalwart foreman of Europe’s largest non-military concrete pour (emphasised in those words many times, presumably to raise the fictional stakes) the following morning; needing to arrange everything over the phone with the drunken Irishman (Andrew Scott), and predictably running into complications with the paperwork, rebar, etc. This metaphor of the foundation - 'you make one little mistake, eventually cracks appear and they will grow' - has to rank among the most tired writing clichés of the modern era. Finally he must explain the situation to his wife (Ruth Wilson) and young boys.

High concept aside, this is a typical Alan Bennet-type script that has been playing in small British theatres off the West End for decades. Locke is the most mundane and overlooked of characters, the sort endlessly documented by these dramas and the unfortunate forte of directors like Mike Leigh. Reliable to a fault, he is intent on both being there for the birth – in distinction to his own father’s poor parenting performance – and making sure the pour goes well, even though he is certain to be fired, referring to the construction as ‘my building.’

Honestly, having met characters such as these outside of their everyman celebration within the stage, generally I find them to be narrow and unhelpful little Martin Bormanns who are more focused on pedantic procedure to the detriment of anything else. The script adds little to this, painting Locke as a disconnected man who believes he can fix everything – ‘no matter what the situation is, you can make it good, like with paster and brick… you can take a situation and you can draw a circle around it and find a way to work something out; you don’t just drive away from it’ he soliloquises. This wears thin quickly, as do Locke’s numerous rants to his father in the back seat (‘I could come for you with a pick and a shovel, I really could, and dig you up’), meant to sketch in background for the character and create emotion in what is otherwise a character marked by his cold collectedness. The only element to break this one-man show transferred holus-bolus from the Rep are incessant phone calls from the supporting cast which will jar the audience, who have presumably come to the cinema to escape the ubiquitous modern presence of the endless ringtone.

Hardy’s performance, while as solid as his character, exacerbates the artificiality of the film – as he chooses, bafflingly, to present an impression of Anthony Hopkins from Remains of the Day for the entirety of the film, perhaps reasoning that the similar character transposed to a modern context would work. The net effect is to give the character a slightly inhuman tone; although Hardy does switch to an impression of a Bob Hoskins (sans accent) drawn from Othello for his asides to his dearest dad. It also does not help the capable supporting cast, who come off as exceedingly shrill and poorly considered in contrast to Hardy’s buttoned down performance. One entire plotline, concerning road closures and local council approvals (yes, fascinating), seems entirely unnecessary and added to pad out the already short running time. The unsubtle portrait of an ordinary, overwritten man rendered by Hardy and Knight is likely to be forgotten by audience members as soon as they leave cinemas, rather like Locke’s real world counterparts.

As always with these dramas, I am left baffled as to what I am meant to take away from these small scale stagings of a mundane crisis in the life of a mundane man. Certainly not anything to do with the detail of the dilemma; as the elements cited above – construction administration, dull domestic duplicity – say nothing in themselves. Is it the loosening of a certain sort of man and his reassertion of mastery in the face of his non-existent father that I am supposed to draw on? Yet there is no compelling break or breakdown with Locke, just a steady assertion that he is a different man and will make it to the hospital. All well and good, but not really much to draw from. Is the film supposed to create resonance and sympathy through the sheer nature of the human condition and the state of modern man? If so, Locke seems the opposite of a character one would want to explore this through; almost anti-human in his unwillingness to loosen his grip or accept that some things may be out of his control. He remains a first act Oedipus throughout – certain of his ability to uncover the truth and assert his control of the situation, in order to triumph in the face of the fates.

The complications of the film and their resolution in closing will surprise no one. The gloss layered over this ironically pedestrian script and performances is gorgeous; the night the car cuts through on its way to resolution is shot beautifully, with muffled streetlights reflected on every surface and light trails creating an eerie ambiance as a background to the film. Although why Locke leaves his driver's light (really, a spotlight) on throughout the entire film is never explained and drifts into the realm of suspending disbelief. The cinematography is sumptuous as it attempts to create interest in its confined set; promotional consideration is most certainly furnished by BMW, with their logo and optional extras given many lingering glances. But ultimately they can do nothing to lift what is a very staid film.

Rating: Two and a half stars.