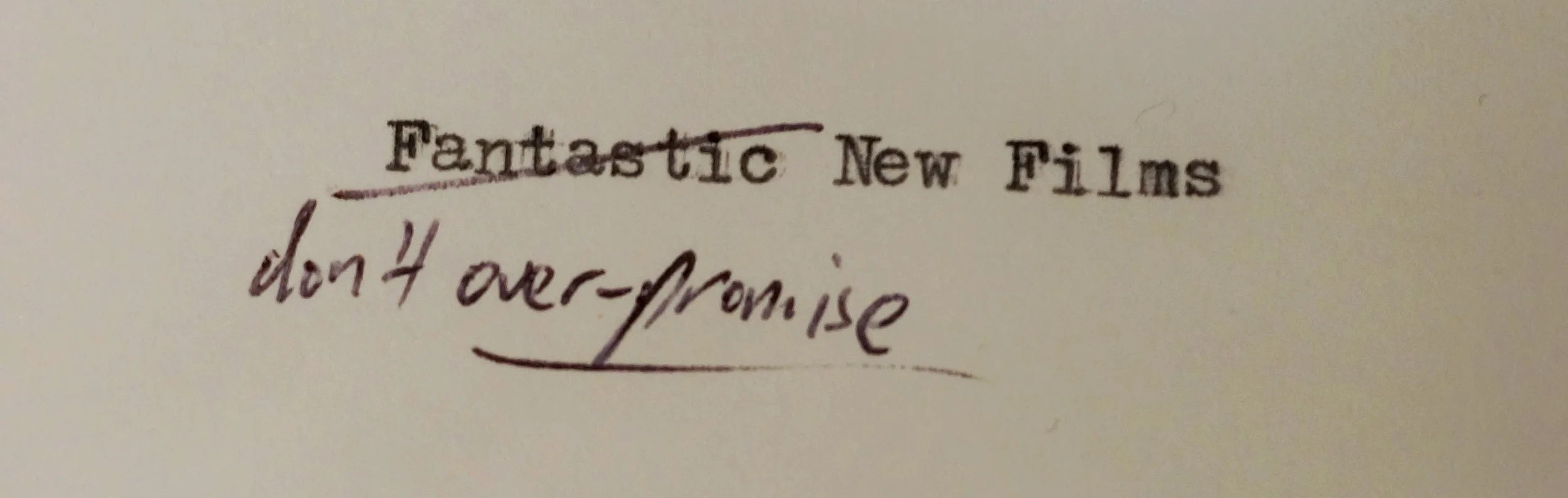

Big Hero 6 can only be described as a bland disappointment; squandering a beautiful backdrop on a child wish-fulfilment fantasy that even four-year-olds will find predictable. That the film refuses to take a risk at any point is symptomatic of the Disney way of making animated features by committees, and aptly represents why more adventurous studios such as Pixar and Studio Ghibli have become more successful and celebrated.

Country: USA

Director: Don Hall, Chris Williams.

Screenplay: Jordan Roberts, Daniel Gerson, Robert L. Baird, and others.

Runtime: 102 minutes.

Cast: Ryan Potter, Scott Adsit, Jamie Chung, T.J. Miller.

Reviewed by Drew Ninnis.

Plot: Hiro is a talented inventor and kid who would rather pit his robots against others in battle than study. But tragedy forces him into the real world, discovering a mysterious plot by a villain to misuse one of his best inventions. Intent on stopping the shady figure, he is hampered and then helped by his brother’s own big, huggable robot – a nurse designed to help Hiro and anyone else in trouble. Teaming up with a bunch of other talented engineers, Hiro sets out to save the world from whatever threat this dangerous stranger represents.

Review: For me, one of the biggest differences between animation giants Pixar and Disney is their general appetite for taking risks. As a studio, Pixar couldn’t exist without taking dramatic risks with story, characterisation, or perspective. A film like Ratatouille, at first blush, doesn’t look like something children and therefore families would be interested in at all, in that the central plot device is a Michelin-star-like battle between a snobby critic and a rat; Monsters Inc. essentially follows the anti-heroes of children’s nightmares; and WALL-E tackles the alien to children issues of climate change and environmentalism through a character that essentially doesn’t talk, surely a huge no-no among otherwise chatty children’s films. In almost all of their films, Pixar tackles difficult adult matters but put a lot of trust in children of all ages to use their natural faculty for empathising and identifying with the good-hearted but struggling heroes of their tales – be they robots, monsters, toys, rats fish… Sure, the accoutrements of a children’s tale are always there in accessible jokes and cute anthropomorphic animations, finished with a shiny pastel gloss, but the beating heart of each Pixar film – and the thing that makes them not just tolerable, but actively enjoyable for adults – is that they capture the fundamental goodness in a sentiment we often lose sight of and have in abundance as children. That natural well of sympathy and interest means that for the viewer it doesn’t matter if they are animated coat hangers, we get it.

Disney doesn’t take risks; indeed, the fact that their animated features now have a Steamboat Willie logo plastered on the front desperately screams for a better time when the company was at the top of its game. But they’ve never understood the lessons outlined above; they are too worried about losing their audience through narratives that might be alien to their target audience’s experience. As an animated studio, even in the 1940s, Disney’s business model was to acquire tried and tested properties – from fairy tales to, well, modern fairy tales and sequels to previous fairy tales – then convert them into a recognised animated style. When you look at their recent animated properties that aren’t either:

(1) Fairy tales and similarly beloved childhood books or their sequels (e.g. Bambi II – oh yes, they made a sequel in 2006, just you wait for Dumbo and Dumber);

(2) Made by other studios, such as Pixar and Studio Ghibli, where Disney is essentially the distributor;

(3) Pale imitations of other studio’s products, such as the ill-advised Planes and Planes: Fire and Rescue;

… you are left with one type of animated film – child wish fulfilment, those along the lines of ‘you’re a wizard, Harry’. Because surely kids will like that, right? So we get Frozen (everyone is a princess with special powers!), Mars Needs Moms (special young boy who must save the world with special talents!), Meet the Robinsons (genius young child inventor with special skills!), etc, etc. That so few of them have been successes (only Frozen seems to rate, and only then because Disney remembered girls watch their films too, and even then she still has to be a princess) seems to teach the studio little about what kids actually want out of a film and what parents are willing to tolerate or buy the merchandise from. The dull, obvious move of pandering to children, we all should have learned, is not the best way to engage kids – indeed, properties like Harry Potter succeed not because we project ourselves into Harry’s special role (he’s really a bland cipher that, at least for me, tended to fade into the background around the more interesting characters) but because we empathise with the things characters are going through and are moved towards a better understanding of ourselves and others when these things are portrayed authentically on the screen.

All of which is a long wind-up, sorry, to say that Disney’s latest animated release, Big Hero 6, is firmly in this vein and mildly disappointing because of it. Set in the hybrid mash-up San Fransokyo, the film’s aesthetic is generic American townie cut with exotic Japanese influences by way of their Saturday morning cartoons. Following the travails of orphaned Hiro and his brother Tadashi, the script unsurprisingly thrusts the genius young boy into solving the mystery of a deadly fire and defeating a seeming super-villain right out of every comic book and T.V. equivalent. Parts of the animation, and the rendering of the surrounding city, is beautifully realised – reminding me a lot of the sort of city the animated T.V. version of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles wanted to realise, but couldn’t on their tiny budget. The mash-up of the two cities is smart, as we get small bits of that great Japanese monster movie setting and a great backdrop from the action. Unfortunately, that that action is generic and rather wastes the lavish world conjured up only to languish away behind it.

Part of the reason Big Hero 6 feels so generic is because the mysteries and beats of its plot follow a patented special-kid family-drama formula, where his initial anger and foolhardiness must be tempered by the usual Spiderman responsibility, Batman forgoing vengeance bullshit. One senses that the relatability of each character to a kid’s everyday experience has been focus grouped to death, missing the point that kids want to go to the movie cinema to see something amazingly different and previously unimaginable – not a repeat of their mothers telling them to clean their rooms (a great counter example would be the recent The Lego Movie, which takes something familiar and seemingly restrictive, then breaks it apart imaginatively). It is ironic that the film so heavily hits the power of imagination message so early in its running time (only to forget it), but shows so little imagination itself. The endless list of scriptwriters – and the fact that the characters are, in true Disney style, appropriated from somewhere else and then blandified – hints at the filmmaking-by-committee that Big Hero 6 reeks of. Predictability is not a sin in family films, but at some point in the general trajectory something a little original and interesting needs to be glimpsed to make it a good family film. Sadly, this is one of the many essential elements missing.

The other reason for the generic feel of the tale is that it walks a fine line between homage or reference and outright plagiarism. That it is so lacking in detail prevents a deeper charge, but recognisable elements of other films, shows, and pop-culture are everywhere. Baymax, the robot of the film, has a design that has been endlessly repeated in other films and in countless variation – from the sleek ship robots in WALL-E, to Robot and Frank, to Revenge of the Sith (think the robot nurse that delivered the twins) off the top of my head. His other attributes hand Studio Ghibli an excellent copyright infringement case against Disney on behalf of My Neighbour Totoro. It also seems no accident that when Baymax suits up for action, he looks dangerously like a cross between Optimus Prime and Astroboy. Earlier sections of the film seem to lift exclusively from TMNT, while Hiro’s partners in action conjure up the usual rag-tag bunch of generic heroes and specific powers. Even the villain is a vaguely familiar Shredder-type character, with a predictable Scooby Doo identity twist at the end. There’s a Stargate knock-off, and even HBO’s Silicone Valley isn’t safe with trademark "witticisms" T.J. Miller and a shifty tech CEO voiced by Matt Ross. There’s an unsuccessful attempt at a copy-cat Michael Giacchino score. Also a predictable ET bicycle moment at the climax. There’s the seeming triumph then sudden reversal structure we’ve come to expect from every big script in the post-Blake Snyder age (and even Pixar is not immune to that). There’s the mandatory post-credits set-up for the sequel.

[Note to my sole reader: I’ve come back to these paragraphs about fourteen times now, as I keep remembering more and more stuff they’ve pretty much just lifted from elsewhere. I’ll stop now, because the case for the prosecution seems well enough established. But you’ll no doubt spot more too.]

It is also a huge disappointment that Disney didn’t chose to put a young, talented girl at the centre of all of this – and perhaps gently challenge a few stereotypes about STEM subjects or gender capabilities or the nature of desires, interests, and communities in the process. But no; young girls are princesses and have special powers granted to them, while young boys have brains and talents and fight for rightful recognition. Anything else would, again, be too risky.

To criticise all of this as familiar would miss the point – because the film has been actively designed that way, workshopped from disparate but successful parts like that undergraduate essay that isn’t original but quotes a lot of different sources. That’s the Disney model, and it illustrates why other more adventurous studios are killing them. It is sad in light of Disney’s golden age of animation, but it is partially the weight of that legacy that is killing them. And like complaining about the latter seasons of The Simpsons, I suppose at some point we've just got to let it go.

It is also exacerbated by the fact that Disney isn’t a studio, it’s a corporation, and takes its tie-ins all the more seriously. Big Hero Six embodies this so much, in its well disbursed action and chase scenes, that it already feels like it is in a transitional state between the film it is and the video game it will inevitably be merchandised into. One scene among the sky-balloons of the city will have audience members unconsciously reaching for their controller. That the characters will be figurined, accessorised, and sold separately is a forgone conclusion for a tent pole film these days – and that is fine – but it is self-defeating when it impinges on the construction of the film itself, creating a lesser product. This defect is unfortunately abundant throughout the film.

A long rant, but how do I sum all of this up? Well, Big Hero 6 is bland and forgettable. Competent and bright, mostly tolerable ... but bland and forgettable. Assembled from market-tested parts, like all post-modern Frankenstein’s monsters it lacks a soul – that childhood imagination igniting spark that makes all of us, no matter the age, pause, ponder, and smile.

Rating: Two stars.