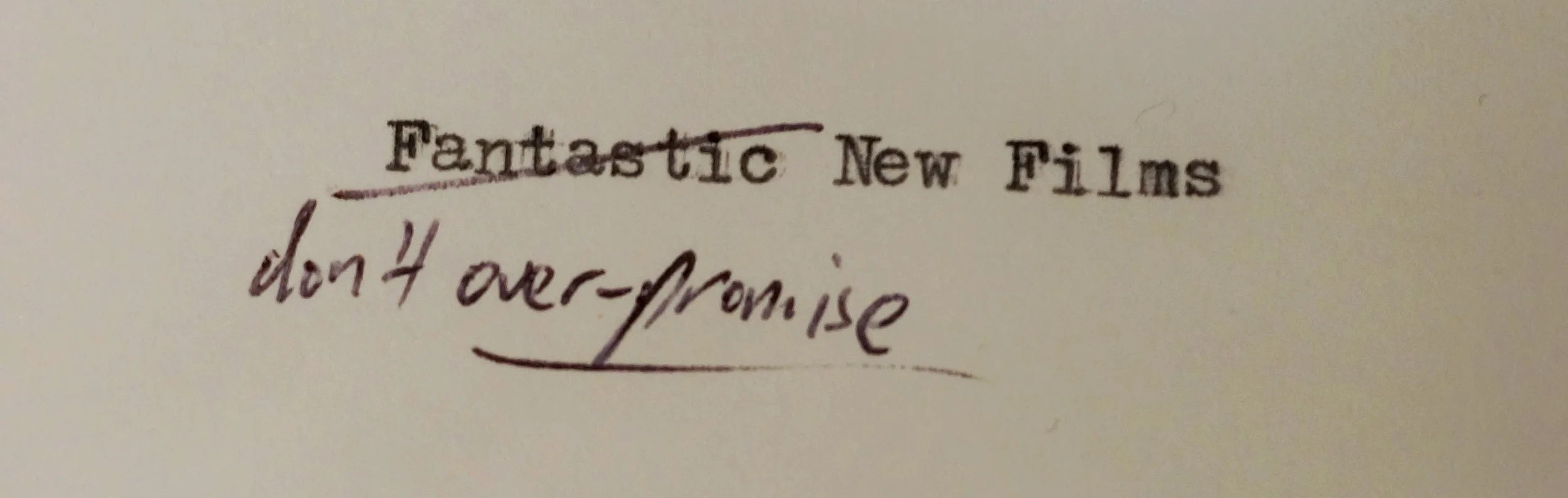

Questions of freedom, the law, and existence are put forth in the powerful Far From Men – a film that is not to be missed. Documenting a moment at the start of the 1954 Algerian war for independence, it follows schoolteacher Daru as he must deliver a prisoner to the closest French garrison to receive justice. Caught between the two warring factions, the men must struggle for their lives and their freedom – throwing into sharp relief the choices they still possess within a world of randomness and contingency. Shot as a thrillingly tense western, the film slowly reveals a magnificent political and philosophical punch.

Country: France, Algeria.

Director: David Oelhoffen.

Screenplay: David Oelhoffen and Antoine Lacomblez. Based on a short story, ‘The Guest’, by Albert Camus.

Runtime: 101 minutes.

Cast: Viggo Mortensen, Reda Kateb, Djemel Barek, Vincent Martin.

Reviewed by Drew Ninnis.

Plot: Set in the Atlas mountains, in 1954 Algeria, Far From Men follows local teacher Daru (Viggo Mortensen) and a prisoner (Reda Kateb) entrusted to his care for delivery to the closest French garrison. Reluctant to perform this duty, Daru and Mohamed must cross dangerous territory where an uprising against French colonial rule is in progress. The two men are unwelcome on either side, and must skirt danger in an attempt to make it to the city unharmed.

Review: ‘Filthy weather, filthier times’ a French soldier and Algerian colonist intones at the beginning of David Oelhoffen’s powerful, poetic new film Far From Men. He speaks to Daru, a local teacher who is initially taken to be a French colonist inAlgeria along with the rest, and upon whom the soldier presses his prisoner Mohamed for delivery to the closest garrison. Mohamed has murdered his cousin in a dispute over his family’s livelihood and crops, and willingly wishes to be handed over to French justice in order to escape the vengeance of his cousin’s family. Matters are complicated by the period and the location – set in 1954, the film opens with Daru receiving news of the Tussaint Rouge (or ‘Red All-Saints’ Day’) where independence guerrillas attacked numerous colonial targets throughout Algeria. The ground that Daru and Mohamed must traverse is contested; indeed, Daru only agrees to leave his schoolhouse after being confronted by both local French colonists and indigenous Algerians, both seeking Mohamed’s head.

Oelhoffen’s direction, and the manner in which he chooses to relate Camus’ short narrative, is skillful in its deftness, light touch, and ambiguity. What seems like the straightforward, and extremely tense, situation of a French man-of-honour charged with doing the right thing by a member of the oppressed population is progressively complicated as we learn more about both Daru and Mohamed. Daru, we discover, is not French; indeed, he is acknowledged by neither side of the conflict, despite serving as a major in the French army during the Second World War. Mohamed, too, is an outcast from his own society and considered as much of an enemy as Daru when they eventually encounter the rebels on their trek. The most poignant scenes of the film originate in that eventual confrontation between colonial and independence forces, with both Mohamed and Daru caught between them and used as bargaining chips. The men Daru encounters at the rebel camp acknowledge him as major and even salute, having served alongside him in the 3rd Algerian Regiment of the French Army. Having now taken up arms against their masters, they still maintain a complicated allegiance to their compatriot Daru. ‘I love you as a brother, but if I have to kill you tomorrow I will’ their leader tells him.

The film and its performances are outstanding, its resonances deep. Mortensen, fresh from an outstanding performance in the cryptic Jajua, is pitch perfect as a character of hidden tragedy and uncompromising principles. Both he and Kateb carry the film between them, which consists of long stretches of their trek filmed against the unforgiving landscape and some heart-pounding moments of tension as they attempt to escape their many pursuers. One scene in particular stands out as emblematic of the superb direction and cinematography, as Daru and Mohamed huddle against a cliff face while the shadow of a rider looms above them. The film is beautifully shot, and the landscape it captures frames their tiny figures as almost nothing yelping against the indifferent majesty of the place. One gains a feeling that many conflicts wash backwards and forwards across the unchanging deserts and mountains. This too is appropriate to the conflict it documents; although this is only a few days in the lives of these men, the war for independence will wage for another eight years with bloody consequence.

The film even manages to capture the spirit of Camus’ writing, and the existential movement that he came to epitomise. Oelhoffen has commented that not only did he base the script on Camus’ short story ‘The Guest’, but that he also made extensive use of Camus’ Algerian Chronicles, which document Camus’ travel to Kabylia in northern Algeria in the 1930s. The inevitable violence, when it comes within the film, is hard, pragmatic, and bracing – stripped of all glamour and full of consequence. The film also deftly captures the sense of absurdity and contingency that is at the core of the existentialist philosophy – Daru and Mohamed attempt to escape the heavy rain by ducking into an abandoned house, only to discover that it has no roof and offers no shelter. Daru makes a choice, and chains his precarious existence to this stranger for no other reason than principle and his own freedom to determine the direction of his fate, if not its course. At the close of the film Mohamed, too, is confronted with a choice – bringing home the existentialist theme of key moments of absolute freedom in a world that is otherwise determined by chance.

Taken as a whole, the film recreates the raw and dusty feel of a classic western – with its strong silent type, honour, death, masculinity – remaining seductive in its presentation, while it slowly complicates this straightforward picture with moral ambiguity and almost incidental resonances with our contemporary war on terror. One moment of dialogue is worth noting in full, for its searing critique and yet light touch. After being captured by French soldiers, who massacre surrendering rebels, Daru accuses their commander:

Soldier: It is bad when veterans turn on us.

Daru: You killed men who were surrendering. That's a war crime.

Soldier: I obey orders. We must eliminate all terrorists on the plateau. Without prisoners. I'm doing it.

Daru: You were wrong to shoot.

‘If the rebels win, where will you hide?’ Daru taunts the colonists at another moment, reinforcing the theme of having no shelter but the actions one must stand by. The law, and its suspension, is everywhere present and discussed almost exclusively throughout the film as different men attempt to act according to their internalised codes. It brings to mind Kafka’s ‘Before the Law’ where a man from the country seeks justice or truth, but can find no answers except the experiences he possesses. It is no coincidence that this a favourite tale among French intellectuals, notably in Jacques Derrida’s own reading – who himself, like Camus or Althusser and others, hailed from the colonial fringe of Algeria and moved to the centre of French intellectual resistance. 'Do you know what you risk there? ... They'll judge you' Daru tells Mohammed, indicating what awaits at the end of their journey when he hands him over to the law.

In short, the film is well worth seeing and studying – it is Oelhoffen’s second film, after In Your Wake, and cements his ‘humanist approach’ to issues of conflict and culture. There is an excellent soundtrack by Nick Cave, and a brilliant combination of camerawork that is simultaneously stately and full of landscape with occasional flashes of intimate and unsettled close-ups. Together, the two somewhat contradictory techniques convey the threat of the contingent, the unexpected, and the tension it creates with the very human intentions of its characters. If I had one criticism, it would be that the film could use less lens flare.

'It’s the law – you cant escape it ... my brothers must get revenge' Mohamed tells Daru, indicating why he must make this journey and simultaneously commenting on the colonial condition. Yet the film remains beautifully ambiguous in regard to how these respective codes and laws should be judged; restricting itself to passing comment on the meaningless amounts of death that accompany them. Only Mortensen’s bravura performance in the final scene offers the most affecting, humanist hope for where we might find meaning and truth. I will be eagerly awaiting Oelhoffen’s next film.

Rating: Four and a half stars.