Bland, unexceptional, and entirely without originality, Giovanni Veronesi’s The Fifth Wheel is a film that is unlikely to cause offence, but equally unlikely to entertain audiences meaningfully. Marketed as an “Italian family film” and delivering what it says on the packet, it is a classic example of the “tax dodge film” plaguing the movie industry.

Reviewed by Drew Ninnis.

Country: Italy

Director: Giovanni Veronesi

Screenplay: Filippo Bologna, Ugo Chiti, Ernesto Fioretti, Giovanni Veronesi.

Runtime: 113 minutes.

Cast: Elio Germano, Alessandra Mastronardi, Ricky Memphis, Sergio Rubini.

Trailer: “The story of a man like many others.”

Plot: Ernesto is a simple man trying to make a living and prosper in life, but is constantly one step behind and finds himself on the bottom of the heap. Spanning forty years, the film shows his development from a young boy with a harsh father to a young lover to a father himself, and all of the typical problems in between. As Ernesto prospers and faces challenges, so too does Italy; and the film attempts to chart Ernesto’s unexceptional but warm life against the background of a changing country.

Viewed as part of the Lavazza Italian Film Festival.

Review: One of the most essential cultural resources that a nation can foster is its film industry; and like many cultural outlets, although many of its products are commercial ventures it takes a certain amount of backing, faith, and gambling on an unappealing product for the almost accidental production of the great independent film. Everyone has their favourite examples of this; and indeed the Weinstein brothers have forged a successful career harvesting the best films that might not otherwise get a distributor and showing them around the world. Michel Hazanavicius’ The Artist is a perfect example of this – a film that had many unique features, most of them not marketable, such as being shot in black and white, as well as being a silent film. The director himself saw it more as a privileged opportunity to experiment and do something that made him happy, rather than something that was ever going to get a mainstream or international release. Yet here we are; the film was moved into competition at Cannes a week before the festival opened, it went on to be shown internationally, and won three Oscars (including Best Picture) for its trouble. It’s a great little gem of a film, one that warmed my heart when I saw it with friends, and a film that I’ll always remember fondly. Without a bit of sponsorship, some tax breaks, some risks, and a few outside chances that great film would still be buried within the imagination of its creator. The lesson is that we should do our best to encourage risk-taking and innovation within cinema; taking the failures as a necessary part of finding some truly great films and voices.

There is a dark side to this, though, and part of it is what I’m going to entitle the “tax dodge film.” This is a film that is also a bit of an act of speculation; but with the understanding that if it does well, for whatever reason, then the money is made back and a little on top; or if it’s not quite as successful, at least a good chunk of government funding and some lucrative tax breaks can make it quite a good deal for investors. The Fifth Wheel is a tax dodge film; and unfortunately, there have been a few of them sprinkled throughout the festival. These aren’t films that are someone’s singular artistic vision; or a vehicle for a passionate performance; or taken up as an opportunity to present a new, different perspective. They are the product of a committee and the interference of producers; which pick a broad, tried and tested idea for a film and deliver very literally on that selected formula, failing to differentiate themselves from the expected fare because that would be taking a risk and eliminate the modest advantage that funding a conservative, lacklustre film like this would offer.

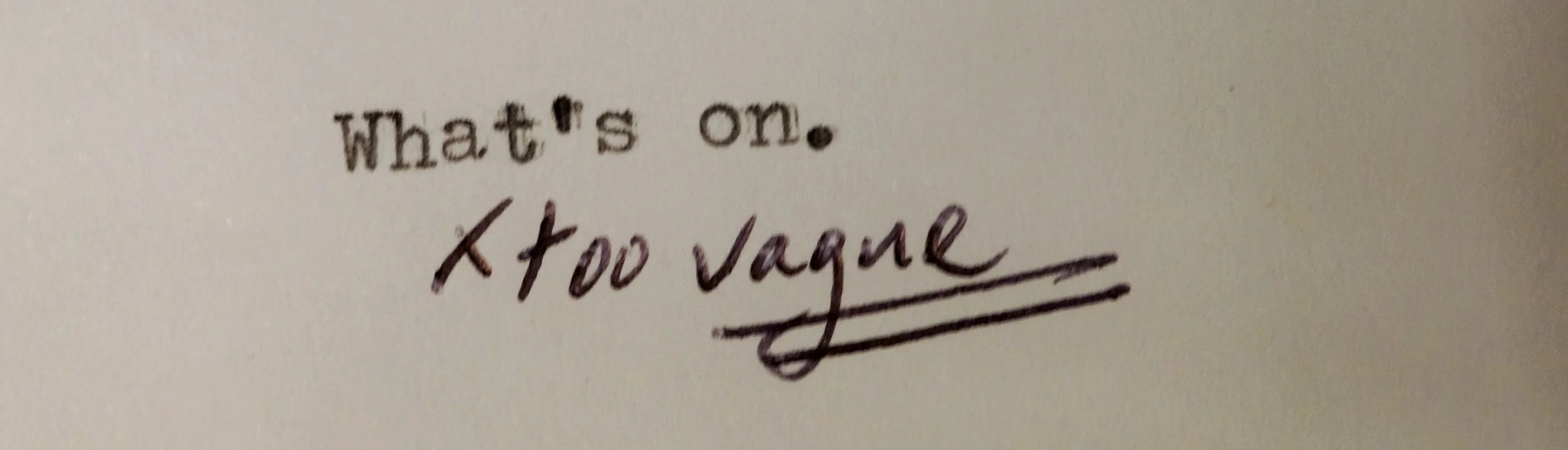

One of the biggest tell-tale signs of this is a script that has more than two writers; more than that indicates that it has either been repeatedly rewritten, or that it is a script that has been drafted by committee. Another is the twenty minutes of a dozen different company or commission logos we have to wade through before we even get to the opening credits of the film. And films put together by committee are almost never successful; they lack a vision, consistency, and sense of direction. All of these problems are present within The Fifth Wheel, which picks that safe genre of portraying the course of time through the life of an everyman. The main scriptwriter draft out the beats of a life story: mean dad, crazy friend, economic ups and downs, some wacky minor characters who are artistic, and the backdrop of popular cultural beats from the last forty years. Other writers are bought on to add pep to individual scenes and contribute zingers to save the script. Finally, the director gets a writing credit because he rewrites, changes, and muddles everything during shooting. A poor editor or editors then has to straighten everything out, and make it look presentable for the backers and distributors.

The French and Italians are notorious for these sorts of films, as they cling like barnacles or parasites to a vibrant film community; inevitably, producers hope to sell not on the strength of a director or performed or an idea, but because it is a “French” film or an “Italian” film where for an hour or two audiences can soak up the wine, the picturesque locations, the sunlight, and the characters acting in a nationally stereotypical way. When the French do this, they generally produce angsty dramas full of affairs and quiet emotional crises filmed in crisp, blue-tinted HD; while the Italians produce a fiery coming-of-age family drama soaked in golden sunlight and arguing around the table. The latter sums up The Fifth Wheel; which is also confusingly being marketed as The Bottom of the Heap – another tell-tale sign indicating that marketers know their audience is choosing to see the film based on its title (book by the cover, if you will) sight unseen. So an evocative, immediately comprehensible title is a must.

The actual film itself is unobjectionable; indeed it is solidly mediocre, as it has most certainly been engineered to be – with a few bumps in the road, some arguments, and broad laughs sprinkled throughout. There’s the self-serious lettering in black and white which opens the film, and hopes to create the impression of an international or arthouse film - i.e. respectability. There’s the usual beats of a son growing up, marrying his first love, having a baby, working hard as a mover, etc, etc. The Italian distinctiveness comes in, something really noticeable over the course of this festival, through the portrayal of economic distress and political corruption – with the main character at one point becoming an employee and dupe for a media company that is funnelling dirty money into politics, while taking its own cut. The honest, proletarian Ernesto misses out, though – and is back to moving furniture towards the end of his career.

He is befriended by a popular, eccentric artist; he keeps revisiting, through circumstance and acquaintance, a local aristocrat’s property (complete with a live, then stuffed leopard – those are the broad laugh parts). Italy beats Germany in the World Cup; now-faded hit songs are referenced throughout, along with the Commodore 64 and other generic touchstones for the audience to relate to. The film closes with the dirty money connected, criminal friend out of prison and reassuring Ernesto’s family at the dinner table that things are going to be different now Silvio Berlusconi is in charge. ‘If a man has a successful business of his own he will make Italy successful too … he’s a man with a positive vision and sound values' the friend remarks, in a broad joke that is far too winking to be funny.

In between there are the usual family-in-law dramas and jokes; with relatives always driving Ernesto to get a better job and pay somebody off to get preferential treatment – ‘This is how things work in Italy if you want to get by,' his father-in-law remarks, 'Mr. Coco can move your application from the bottom of the pile to the top.’ This does occasion the one truly funny scene within the film (and even a tax dodge film strikes on one or two good moments, almost by accident) where Ernesto attends an almost Master Chef-like challenge where he must cook something to become a school chef. Of course he cannot, his wife does all the cooking, and the intervention of the aforementioned Mr. Coco (with palms suitably greased) leads to an amusing debate about the fundamentals of cooking with the interviewers and Ernesto wining the job without touching a single pot, pan, or ingredient.

Everything else smacks of its unexceptional, middle-of-the-road-ness and the film has nothing substantial to recommend for itself. You aren’t going to actively squirm in your seat if you were forced watch it; but it isn’t a particularly entertaining or memorable film either. The passage of time is marked through shots of programmes on T.V. and various football matches. The final act relies on a silly lottery ticket drama encapsulates the deep unoriginality of the film. There’s even an epilogue to tell you of the subsequent lives of these entirely fictional characters, which seems faintly ridiculous and unnecessary – as if the film wasn’t so relentlessly predictable, I wouldn’t have the ability to scry their fates in the crystal ball of my imagination myself.

Mediocre, unimaginative, banal, plain – the problem is that these aren’t criticisms of a tax dodge film. They are entirely its point and the aim; and that’s the dilemma. Public and private sponsorship of the film industry is essential to getting unusual, potentially great films made. So I’m not sure how to combat rampant abuses of this system, like The Fifth Wheel. I suspect we just have to put up with them; and remember that when we see something miraculous, like The Selfish Giant, it succeeds on top of the corpses of a dozen films like The Fifth Wheel. That thought, at least, got me through this bland porridge of a film.

Rating: Two stars.