It takes a lot of courage to represent a vagina on screen, and lord knows that shouldn’t be the case – a condition Vulva 3.0 sets out to cure. A documentary about the many hidden facets surrounding vaginas, their representation, and censorship the film opens up a brave dialogue that holds the promise to dispel prejudices and undo decades of normative fixation.

Country: Germany

Director: Claudia Richarz, Ulrike Zimmermann.

Screenplay: Ulrike Zimmermann. (Documentary)

Runtime: 79 minutes.

Cast: Christoph Zerm, Claudia Gehrke, Marion Hulverscheidt, Mithu Sanyal.

Reviewed by Drew Ninnis.

Viewed as part of the Canberra International Film Festival.

Plot: Vulva 3.0 is an outstanding documentary about the representation, censorship, norms, and issues that women confront in relating to their vaginas. From sexual education, to art, to surgery, to pornography the film thoroughly and intelligently explores every angle through a series of interviews with experts, publishers, doctors, and activists. It is a documentary of the highest order; opening up a much needed discussion.

Festival Goers? See it. Drag reluctant (adult) friends along.

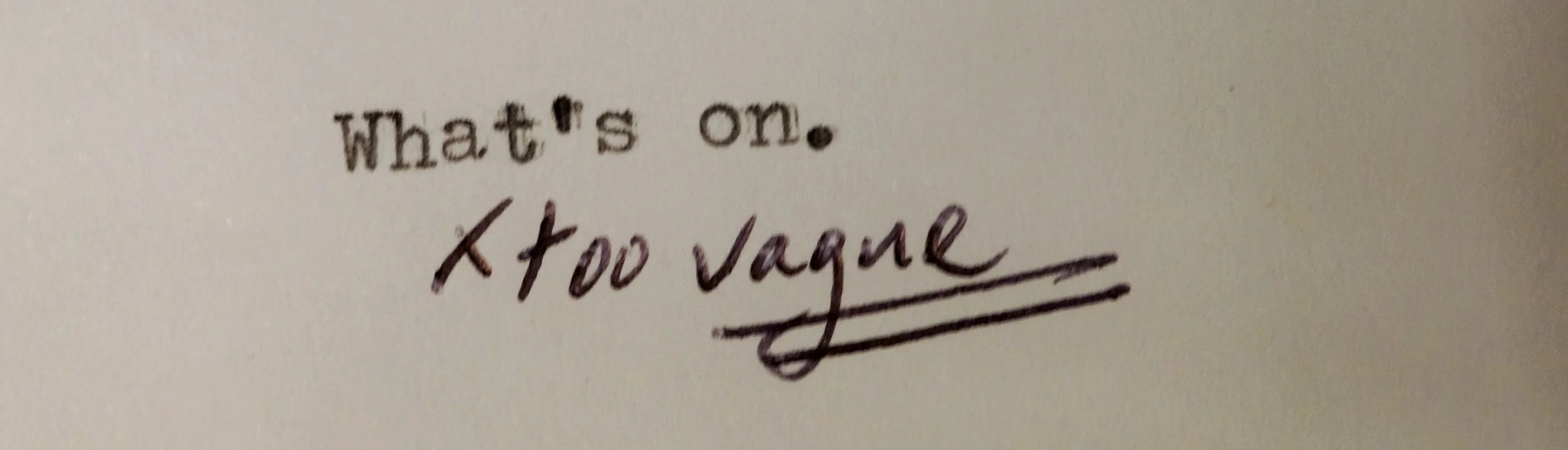

Review: It takes a lot of courage to represent a vagina on screen, and lord knows that shouldn’t be the case. Thankfully Claudia Richarz and Ulrike Zimmermann’s masterful, concise documentary is here to explore that very issue – examining the vagina from all angles. Not only do the directors deserve praise, but also the programmers of the Canberra International Film Festival – who have included it as part of the programme for this year. One writer amusingly describes the myths that surround the vulva as:

Showing the vulva scares off bears and lions, makes wheat grow higher, calms storm tides and demons fear it. The devil runs away. Showing the vulva can save the world. The vulva is omnipotent.

A film dedicated to the vulva dispels more than just fictional devils and demons, but the strange preconceptions and censorship that continues to surround a simple body part in our supposedly liberated age. The film intelligently and insightfully starts with a fundamental, normative squeamishness that women have with confronting their own body, through the lens of sexual education and the representation of the reproductive organs. The politics of even making a model of the female reproductive system, or representing it within medical texts, is fascinating in its absurdities and inspiring in the manner in which key figures are working to open up these issues.

On showing teenagers photos, one expert remarks that ‘the girls find it all too icky.’ Yet, as publisher Claudia Gehrke remarks ‘some female artists, or they in particular, deal with their own bodies first.’ This leads to some startling and honest work, that Gehrke publishes annually in an edition entitled The Secret Eye, which aims to explore the meeting point of art and social representation of these issues. This is counterpointed with a photographer and editor, who spends his days airbrushing out inner labia and other supposedly offensive sights to comply both with German obscenity laws and the expectations of consumers purchasing pornography; describing his job as making sure the ‘image appeals to normal thinking people’. ‘And now I doubt this will bother anyone’ he says without a trace of irony, having removed a hint of labia from a picture of an ostensibly beaten woman covered in dirt and crawling across exposed planks and rubble. The film needs to present no commentary to establish its vital point. Labia, it seems, cause the most angst among everyone – considered unsightly by a mysteriously oppressive “public,” and the subject not just of airbrushing but in many cases surgery. As the film deftly shows, the tyranny of the norm predominates. ‘We’re back to the idea of invisibility being the ideal of beauty,’ Gehrke remarks, in a film positively overstuffed with insightful statements.

Gehrke’s work is fascinating because it leads the film to a further exploration of censorship; with the German Bundesprüfstelle für jugendgefährdende Medien or ‘Federal Review Board for Media Harmful to Minors’ who have, in fact, been called upon by members of the public to investigate Gehrke’s publications. People are scandalised by representations of the vagina; with the chair of the board describing the claims against The Secret Eye as effectively ridiculous, so obvious is their artistic merit. Even that does not stop the strange shadow cast by the issue. ‘We’ve inherited quite a legacy here: the fear of people with no clothes on. Strange, isn’t it?’ he remarks. Yet the film is also adept at exploring other confronting issues, such as female circumcision, and much time is spent with activists and educators, one of whom has direct experience with the issue. As she lists the four types of female circumcision classified by the World Health Organisation, you desperately beg her not to enumerate type number four. It is confronting but essential material; strangely like the normal, unexceptional photos of women’s vaginas themselves – sprinkled throughout the film. By the end, the images have been naturalised and drained of any other prejudices – an accomplishment for the film in itself.

The final section documents labial plastic surgery as a booming industry, going so far as to show a conference of surgeons observing an operation in real time. ‘Anyone who cares about their appearance should have it done’ one patient remarks, as the surgeon coldly elaborates the operation. The surgeon herself is likely to draw the most ire from audiences, using common trade terms and remarking ‘this is what we call “cauliflower like” ’ in relation to an otherwise unexceptional picture of inner labia. The doctor herself is a high priestess of normative expectation; tied up as it is with her economic interest, and a far cry from the re-constructive surgeries the discipline was created to address in the wake of World War Two. One gynaecologist, specialising in Female Genital Mutilation and educating midwives about it, refers to the dilemma as a “Procrustean bed” which mythically stretches each traveller to fit its length. The parallels between the modern surgery and female circumcision are almost too much to bear; and the film is smart in its structuring of the material. After one public lecturer, an educator describes an educated African man coming up to her who has a girlfriend in Germany and a wife back home. He simply thought the difference was due to racial features; completely oblivious to the mutilation his wife experienced.

And yet the message of the film is rightfully upbeat; it identifies, in a fully Foucaultian tradition, that critique and open discussion quickly dispel any prejudices or preconceptions and leads to a genuine inquiry into where these normative desires come from. Talking clarifies and exposes; and Vulva 3.0 is at the forefront of that admirable effort.

Rating: Four stars.