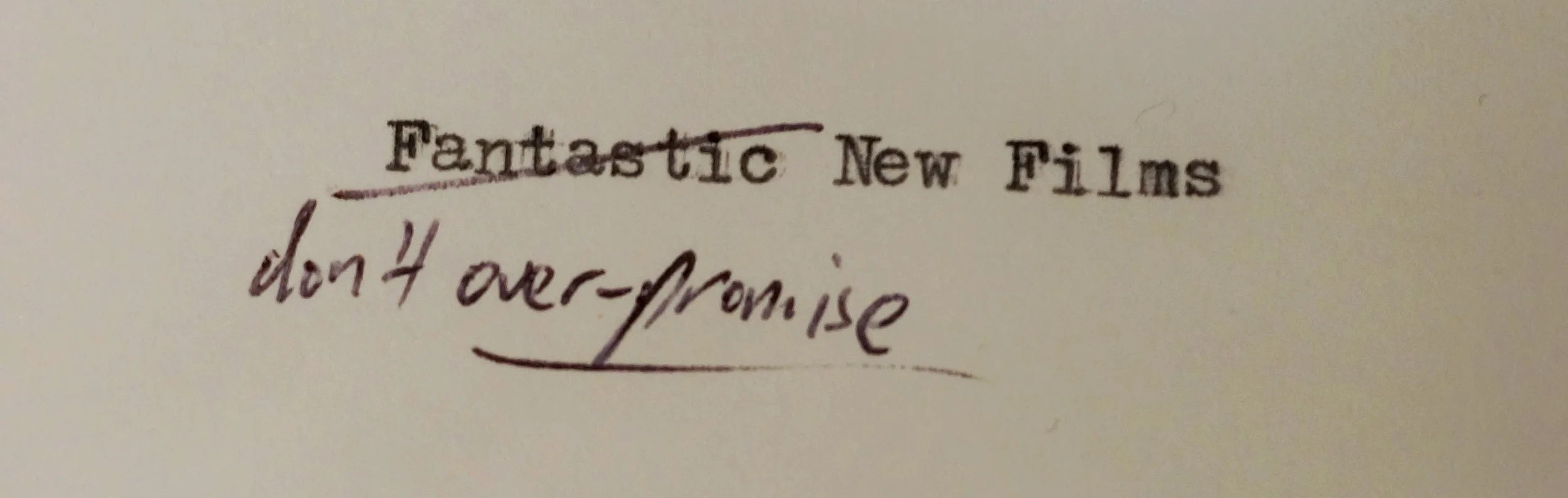

Damien Chazelle’s Whiplash is an intense, confronting, and brilliant film. Documenting the toxic relationship between a teacher and his students at a prestigious New York music conservatory, the resulting battle of wills is riveting. This stunning film is an indictment of an entire generation of abuse.

Reviewed by Drew Ninnis.

Country: USA

Director: Damien Chazelle

Screenplay: Damien Chazelle

Runtime: 106 minutes.

Cast: Miles Teller, J.K. Simmons, Melissa Benoist, Paul Reiser.

Trailer: Chairs will fly.

Plot: Aspiring drummer Andrew wants to be more than good, he wants to be the next Buddy Rich. Catching the eye of distinguished teacher and bandleader Fletcher, Andrew is elated that success is opening up for him. But Fletcher is more than a perfectionist; he is an abusive, demanding teacher who strips down his students and demands they rebuild themselves into better performers. The two engage in a riveting battle of wills, as Andrew works harder and harder – physically destroying himself – to meet Fletcher’s expectations.

Review: Damien Chazelle’s Whiplash is an intense, confronting documentation of a form of abuse that is both common and ignored, cloaked as it is in the myth of the great artist triumphing through adversity and challenge. It follows aspiring drummer Andrew (Miles Teller), a freshman at a prestigious New York music conservatory who is determined to be successful within the art form he is so passionate about. Spotted practicing diligently late at night, he is approached by the abrasive, dismissive shining light of the school – teacher and bandleader Fletcher (J. K. Simmons) – in what will turn out to be a modus operandi for the character. Fletcher thinks he sees something in the kid, and gives him a chance to play as an alternate within the jazz ensemble he directs. It is a dream come true for Andrew, who seizes his moment to shine and impress Fletcher – when the drumming charts are lost before an import gig and the drummer he understudies can’t go on without them. You’re up kid, Fletcher indicates; gifting Andrew the opening beat in a musical rags to riches story that’ll see him suddenly discovered, land a contract, and become the greatest drummer the 21st century will ever know.

Or that would be the case, if this were any other Hollywood film. Shot in 20 days on a modest budget, writer-director Chazelle has something completely different and much more personal in mind; showing the self-destructive ride through hell Andrew undertakes to meet the standards of a man who can’t be pleased and some will suspect, doesn’t want to be. Whereas any other film might take theBlack Swan meets Centerstage route of “they dance what they feel” (and many are already making an asinine comparison to the former),Whiplash wants to show you, step-by-step, the degrees of obsessiveness and physical punishment that a vulnerable artists undergoes to make themselves shine in the eyes of a father figure that has no intention of loving them back. Fletcher is a terror; drawing students in with honey and an attentive ear, then hurling back abuse of the most personal and intimate nature. The psychological abuse becomes literal physical abuse at points, and anyone who has even seen the tailer for the film will already have a taste of the terror J.K. Simmons invokes in his high octane performance.

Yet Miles Teller is just as formidable, playing the immovable object to Simmons irresistible force and pushing himself to prove the man wrong. That’s exactly what a character like Fletcher is banking on; knowing that the figure who withholds approval will always be more psychologically powerful than the teacher who offers life lessons and lollipops, a lá Dead Poets Society. The film is heavy on melodramatic incident, but paces itself with an irresistible acceleration that will sweep away any doubts in the mind of the audience. The portrait of these two combatants, and the collateral damage to others, is pushed to the limit in an effort to hammer home the emotional point Chazelle is trying to make. All of this leads to a bravura, troubling last scene that closes out the film with an extended performance and will have many deeply uncomfortable about the message it sends.

That perhaps is Chazelle’s point, as he’s highlighted in interviews that he’s no stranger either to drumming (and knows how to compellingly film it), or to the obsessiveness and damage that a teacher of that kind of force can produce in a student eager to please through their passion. The director shatters more than just the myth of the inspiring teacher in this film, as he exposes yet another node of power within structures of abuse that have plagued our institutions for decades – and are only now seeing the fiery light of critical scrutiny. Fletcher’s rationale – expressed during an unsettlingly calm, eye-of-the-storm bar scene within the film – is that there ‘aren’t two more damaging words in the English language than “good job”,’ painting himself as a champion against a new-age, politically correct culture that gives everyone a trophy. Yet at this point in the film the audience is left with no doubt that this is just cheap cover, and that there is no end that will justify these means. Quite the opposite; even if Andrew does succeed it will be despite rather than because of this abuse – a point which is almost impossible for the emotionally abused to absorb, even years later. The human tendency to make a strength out of a trauma, and sometimes even repeat the cycle, underpins the whole logic of that approach.

Whiplash pulls back the curtain on that bankrupt myth in the microcosm; but the message resonates on a grand scale. The guilty mentality of “practice harder” is built in to our society at this point; laying blame where success doesn’t follow hard work, as we’ve always been told. Every beat and beating is writ large on Teller’s open, expressive face; and Chazelle shoots Teller while drumming as a body in a frenzy, caught up in the gears of an unyielding machine and bleeding itself in an attempt to achieve an impossible double-time. The sacrifice of the artist is another virtue that comes in for a sharp critique; as we see Andrew act on his puppy-dog crush for a pretty snack bar attendant (Melissa Benoist) at the local cinema, only to unquestioningly discard their blossoming relationship when Fletcher demands he refocus on his work. Over and over, Fletcher repeats the same refrain to Andrew, in gloriously perverse self-justification – the careworn story of a night in 1937, where a 16-year-old Charlie Parker steps into the limelight as a guest of Count Basie’s orchestra, fucks up a chord progression, and drummer Jo Jones contemptuously throws a cymbal at Parker’s feet. Fletcher misremembers this as a violent act of it being thrown at Parker’s head (it wasn’t, more sardonic, with laughter and heckling from the audience), but the kid fresh out of high school is driven by humiliation to refocus and become the best saxophonist of the 20th century (Chazelle’s script puts Parker down as the ‘best musician,’ but that’s laying it on a bit too thick, particularly with Buddy Rich plastered all over Andrew’s walls). What Fletcher doesn’t mention is Parker’s well-known decline, heroin addiction, and death at thirty five.

Yes, there’s a balance between challenging someone and supporting them. But ultimately this is not what Whiplash is about; despite his professed intentions to the contrary, Fletcher’s character is an abuser who is interested in nothing but his own ends, and in all probability was a victim of the same treatment himself. We are experiencing a broader moment in time within which the institutional abuse of a generation is unravelling for all to see, as well as the ways in which some have perpetuated it. Be it child sexual abuse in the Catholic church or elsewhere, the stories your parents tell to aghast kids about a different era of corporal punishment in schools, or simply the individuals still around today who believe that creating a hostile environment within a discipline or workplace is a moral and ethical thing to do.

A whole structure is collapsing; and Damien Chazelle’s Whiplash speaks from an intuitive place about this slow collapse and its timeliness, documenting one form among many of the damage that brutal system has caused. Audiences may feel ambivalent towards the film’s closing scene; but we can’t feel ambivalent about doing everything we can to end every form of abuse, anywhere and everywhere we can. Whiplash is an explosive and timely reminder of that.

Rating: Four and a half stars.