Studio Ghibli's poetic and profoundly philosophical The Tale of Princess Kaguya is beautiful. Simply beautiful. The film offers viewers something unique within cinematic experience and modern life – space, breath, and simplicity. It combines them in a mysterious richness that Western art has never been able to master.

Reviewed by Drew Ninnis.

Country: Japan

Director: Isao Takahata

Screenplay: Isao Takahata, Riko Sakaguchi.

Runtime: 137 minutes.

Cast: Aki Asakura, Yukiji Asaoka, Takeo Chii, Isao Hashizume.

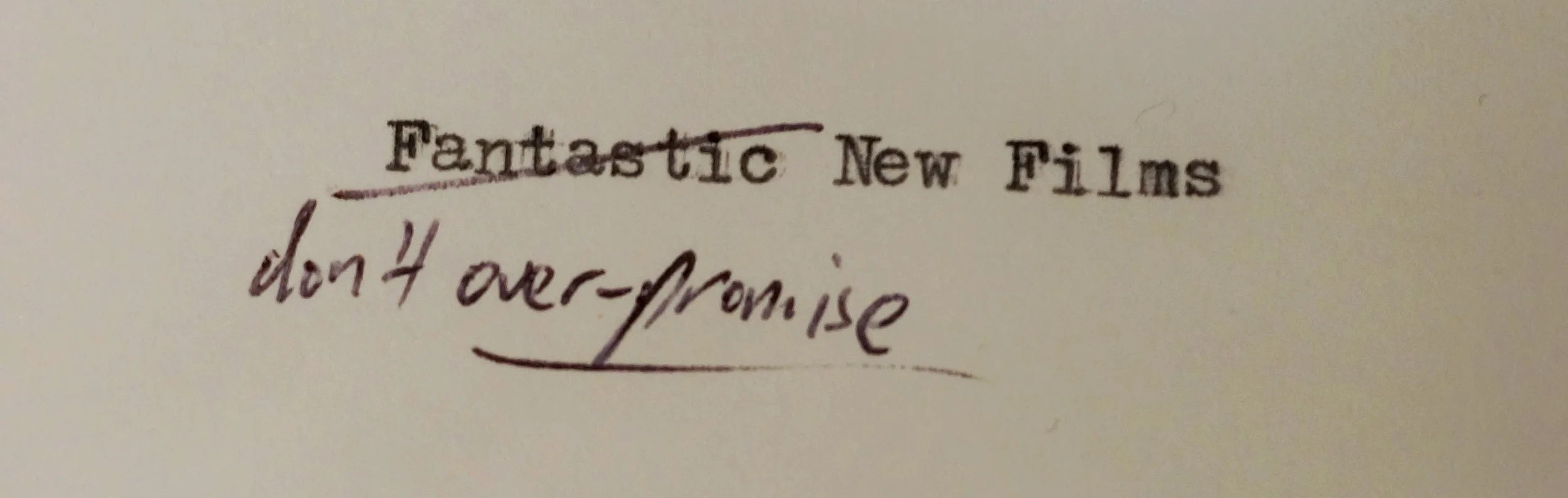

Trailer: Beautiful. Make sure to see the subtitled version.

Plot: Based on The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter, a 10th century Japanese folktale, the film follows Princess Kaguya as she is found in a forest of bamboo by a humble bamboo cutter, and is raised as his daughter. Recognising that she is a princess, and suddenly finding riches within the forest, he takes her to the capital where she grows up into the most beautiful young woman in Japan. Courted by the most powerful nobles, she sends them on a quest to prove their love – all the while yearning to return to the countryside, and the simple peasants she knew.

Review: The Tale of Princess Kaguya (Kaguyahime no monogatari) is sheer poetry, an enticingly simple watercolour that overflows with feeling and meaning. Gathering together the riches of Japanese literature, painting, music on screen, the film is the crowning jewel of Isao Takahata and Hayao Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli – entirely fitting and sad, considering that this animated feature may be the last the studio produces. It is testament to the power of animation as an art form, and the film reaches back into the distant past of Japan to adapt The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter; a 10th century tale which is the oldest existing Japanese text, and thought to be based on even older folktales. When one opens oneself up to this film, it fills the soul with something almost spiritual and imparts an ambiguous meaning that one must meditate on for days, months, even years. The film is a profound accomplishment.

The tale is familiar to most Japanese children, and the parents who have passed it on, but at first might seem quaint and unusual to foreigners. An elderly, childless peasant labours as a bamboo cutter in the forest, dutifully going about his day’s work. He comes across a shining bamboo shoot, seemingly blessed by the moon, and containing a tiny sleeping princess the size of his thumb. Rejoicing and cradling her gently in his hands, he carries her home to his wife where the tiny princess transforms into a baby. The couple vow to raise the child as their own; and she grows up fast, into a cheeky toddler fascinated by the natural world and then a young girl who is adopted by the local children and shown how to relish a stolen melon, or how to catch frogs. The bamboo cutter, meanwhile, finds that whenever he cuts down a stalk he reveals a nugget of gold and quickly becomes rich. He interprets this as a sign the heavens wish his daughter to become a true princess, and takes her away to the capital to enter her into the ranks of the nobility.

The beauty of the young girl, and her ability to play the sweetest music effortlessly, entrances the young nobles who compete feverishly to win her favour. One compares her to a jewelled branch from a magical tree on the island of Hōrai; another to the stone begging bowl of Budda himself; a third suitor to the legendary robe of the fire-rat of China; the fourth to the coloured jewel from a dragon's neck; and the last to the mythical sea snail born of a swallow. She accepts their compliments, and agrees to marry the one who can bring her the impossible treasure to which they have likened her. All try, but several find only their deaths, and the others purchase the most expensive forgeries only to have their trickery exposed and their fortunes bankrupted. Princess Kaguya is finally happy and at rest, although yearning for the life of the country. She tends a small garden that, when viewed from the right angle, could be the countryside in miniature; and helps her mother weave fine fabrics.

But the princess attracts the attention of the Mikado, who is accustomed to possessing all that he demands and attempts to force himself on Princess Kaguya. She makes a wish to the moon to escape; and in doing so, lifts the veil and understands that she has come from Capital of the Moon (Tsuki-no-Miyako), and came to earth after hearing a beautiful song (‘come round, o distant time / come round, and call my heart back’) and wanting to see the lands of the mortals it describes. Thus she was sent to the earth; but in that moment of realisation she understands that she must return to the moon, and assume the feather robe which will make her forget the pleasures, sorrows, and attachments of life among the people of the mortal realm. Knowing this, she wishes desperately to stay, but cannot. Despite her father’s loving attempts to defend her, a heavenly entourage descends and returns her to the moon.

The adaptation is beautiful; faithful in spirit to the tale, yet departing in fundamental details to truly communicate the Zen Buddhist message of the joy and sorrow of life, and the necessity of being able to say goodbye to all one loves with the hope of meeting these joys again. There is a minimum of the trademark magical realism that, in my humble opinion, blights the true expressiveness of other Studio Ghibli films – here, Isao Takahata refines the tale to express the gentle poetry of the myth. 'This is very strange, you know' declares the father, in a moment of levity and insight. The exquisite illustration of the film is like the finest porcelain brought to life; tiny details, like the texture of Princess Kaguya’s hair, steals the breath away. The film lingers on the small, exceptional details of flowers and forgotten creatures. The sounds of nature and of a music intimately connected with it accompany the images.

The smallest touches captivate the most. As the infatuated nobles kneel before Princess Kaguya, her faithful servant moves behind them unnoticed, placidly straightening out the trains of their ceremonial dress, in a light gesture worthy of Kurosawa’s existential portraits. The film offers viewers something unique within cinematic experience and modern life – space, breath, and simplicity. It combines them in a mysterious richness that Western art has never been able to master. ‘Even a princess must sweat and laugh out loud sometimes’ remarks the young girl, who is declared ‘the shining princess of the supple bamboo’ on her naming day.

There is a conclusion to the tale, not shown within the film, which is equally beautiful and mysterious. Stricken with grief, Princess Kaguya’s parents pass from the world. The Emperor, hearing of her departure, receives a letter written by the princess before departing and orders it burnt, asking ‘which is the closest mountain to heaven?’ while hoping it will reach the Princess. Without her, he wishes only to die. That place is, of course, Mt. Fuji – the immortal mountain.

Rating: Five stars.