Country: USA

Director: Matt Reeves

Screenplay: Amanda Silver, Rick Jaffa, Mark Momback.

Runtime: 130 minutes

Cast: Gary Oldman, Keri Russell, Andy Serkis, Jason Clarke.

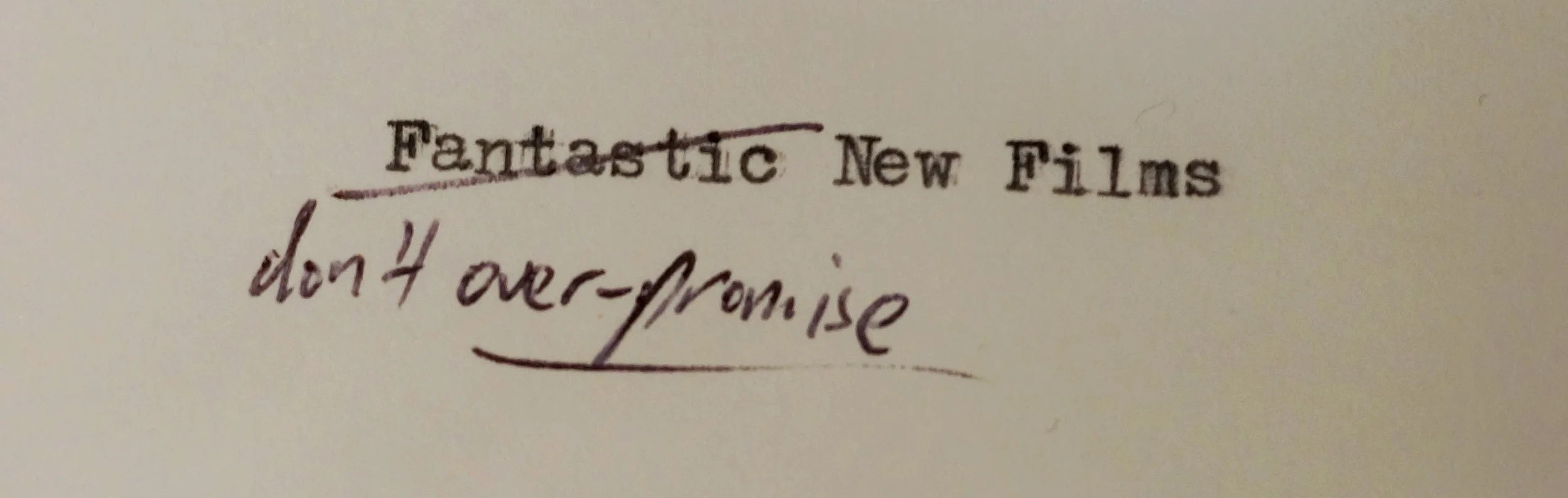

Trailer: “But we are survivors!” (warning: many of them aren't.)

Plot: With the human race almost wiped out by a genetically engineered virus, a rapidly evolving group of apes find themselves at peace and home perched atop a dam outside San Francisco. But that peace is not to last, as survivors from the city arrive to get the dam back into operation; and both parties must navigate a delicate balance to avoid a war that might wipe both of them out.

Review: There is not much to say in qualitatively assessing Dawn of the Planet of the Apes; it is a studio tent-pole film that is probably best seen on a long-haul flight from one continent to another. It fills the frame with cgi-ed spectacle, alternating with overblown pathos. But the ethos is thin, and the logos non-existent; both are replaced with common tropes that the audience can follow easily, even if they have fallen asleep during the first half. Is there any point in criticising this sort of film making? There is obviously a market for it, and had I been on a plane perhaps I would even have enjoyed it more. Everything about the film is adequate and safe; an assessment that could have been written almost before even viewing a film like this.

Here’s a well worn cliché of criticism of our own: Chekhov’s gun. In his advice to fellow playwright A. S. Lazarev, Chekhov writes that ‘one must not put a loaded rifle on the stage if no one is thinking of firing it.’ Later, in his Memoirs, he is cited as saying:

If you say in the first chapter that there is a rifle hanging on a wall, in the second or third chapter it absolutely must go off. If it’s not going to be fired, it shouldn't be hanging there.

The two pieces of advice have been interesting conflated into the modern advice that “a gun introduced in the first act must go off in the third”; however, what we have missed in this is an interesting difference between the two statements of what is ostensibly the same advice. The first statement (lets call it A) is advice on the staging of a play and symbolism, while the second (lets call it B) refers to the novel and plot.

In A we have a principle that speaks to the economy of the stage; the play is a form which is naturally limited in terms of time and space, imposing the physical restraints of the staging upon the narrative. We also have the careful wording of ‘thinking of firing it’ – the gun need never be fired, but it needs to be a threat that is essential to the themes of the play. In A, the gun is dominant element that must be integrated into the subject matter of the narrative, usually through being symbolic; it represents a choice that this element is more important in establishing an effect in the mind of the viewer than any other element that could have been chosen to fill that limited space. In Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler this element is a giant portrait of her father, the General, who is mentioned fleetingly throughout but is symbolic for the battle that Hedda is engaged in. He is simultaneously the source of her strength and wilfulness; and also a symbol of the old order which prevents a woman like Hedda from expressing that will.

Statement B is subtly different. It refers literally to the action; to a gun going off, or an essential plot element that is introduced and must play a part in the dénouement or at least be resolved. This is because it has been specifically singled out, commented on, and therefore plays an important point in the plot. The gun need not be symbolic; it is just a means to an end. It is also significant that here Chekhov is talking about the novel, which has more space than the staging of a play to breathe but must still justify the author’s choice in bringing this element to your attention rather than that. Even Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle, full of mundane descriptions of everyday objects, selects those objects carefully because they give an essential texture that brings the mundane alive and steeps it in the truthful. B suggests the essential functioning of the element as part of the plot; and plot elements emphasised heavily but dropped are unsatisfying. Again, in Hedda Gabler, the elements that reflects B are literally guns introduced; the duelling pistols introduced in the First Act are used to take her life in the Fourth.

Somehow, contemporary screen writers have gotten it into their heads that the interpretation essential to Chekhov's Gun is the second one; plot elements must be resolved, and good writing consists of introducing those elements early so they can go off meaningfully later. But this is not good writing; this denudes the elements of that essential meaning statement A implies – that more than being just a machine part of the plot, these elements are symbolic and embody the conflicts or themes that run throughout the film. Even in Hedda Gabler the pistols belonged to the General, and Hedda’s use of them shows how she is a woman empowered beyond the gender norm, but also that in her context this empowerment dances with death (she plays a tarantella on the piano before shooting herself in the final act, a dance of hysteria and death). Chekhov Gun is an element that draws meaning into it, distorting the flow of the narrative to focus us on why it is a narrative that should be told; in effect, why it is an exceptional narrative to be documented.

Dawn of the Planet of the Apes is full of denuded guns; so much so that when element A and element B get into close enough proximity with each other, the narrative unlocks in the viewer’s mind and becomes a series of landmarks to be plodded towards and hit. The fuel of this plot’s engine is trust between apes and humans, and the script quickly sets a clock on the scenario – if the dam is not running in three days, the humans will attack and take it from the apes. This establishes the beats of the film as moments when this trust will either be built or compromised; Malcom and his family, sent to fix the dam, will build it, as will the honourable ape leader Caesar (played here by Ned Stark). Koba, the Scar of this Lion King, will erode it through his hatred of humans, as will his inverse in the human camp Carver. Oldman’s character, Dreyfus, as the human leader will be a weathervane moving from one side to the other and back, as will his ape counterpart (and son of Caesar) Blue Eyes. No trust, everyone dies; enough trust, everyone lives happily and peacefully ever after. The terms of the next two hours are established.

Now the denuded Guns are introduced. Caesar’s wife is sick after the birth of their child, Malcom’s wife Ellie is a doctor; +1 trust chip, to be played at the script’s leisure. Hothead Carver hides a gun because he doesn't trust the apes; -1 trust chip. Son Alexander draws and reads, while sensitive ape Maurice teaches reading through pictures; +1 trust chip. Koba hates humans and stalks them to find evidence that supports his agenda; -1 trust chip. Dreyfus sends human mission to the apes; +1 trust chip. Dreyfus prepares humans to attack; -1 trust chip. Dam is restored; +1 trust chip. Defeat is snapped from the jaws of victory; -1 trust chip.

All of these elements are in some way set up or foreshadowed in the first half of the film; they are then dutifully triggered when needed in the latter half. This is played out amid a sea of broad tropes; the destructiveness of humans, but also their thirst for survival. The ape’s redeeming connection to nature, but also their anthropomorphism and contraction of close-proximity humanness. At one point Caesar cites the values he lives by – ‘Home, Family, Future’ – and his fear they might be lost in war (he should run for public office on that platform). The narrative setting is comfortable; we don’t know when the beats will come, but we know them when they arrive. The +1 chips and the -1 chips are added up; leading to a split vote that is meant to induce tension. Knowing the conventions of a film franchise as we do, though, we know that the ending will be satisfying enough that the Good ekes out a slim victory, but dark enough that it will ground the stakes of the next inevitable film. Overall, the script is not even a formula; it is a 130 minute exercise in narrative accounting.

And the performances? Impossible to say. The emotional beats are so big that the demands on the actor’s skill are minimal. Half of the actors are voiced over and animated; this CGI effect is contagious to the live-action counterparts. The aim is to make a part-CGI film look entirely real; the effect is to make a part-real film look entirely CGI-ed. It makes you long for the days when skilled body artists donned fur to give expression to these colourful beasts.

Ultimately, the message is – what? I forgot, immediately on leaving the cinema. I’m left with some vague tropes: humans will always find a way to fuck things up; nature is good, but savage and unforgiving; civilisation brings wonderful technologies, but is a refined form of barbarism.; families are good, and kids are wise fools; you have to let the traumatic experience of being locked up in a cage, being tortured and tested on, and treated as a worthless thing by your captors go or otherwise you’ll turn into the thing you hate. None of these is really worth sustained scrutiny, but tent-pole films aren’t meant for scrutiny. They’re meant for long flights.

Rating: Two carefully foreshadowed guns.