Reviewed by Drew Ninnis

Country: USA

Director: Fred Schepisi

Screenplay: Gerald Di Pego

Runtime: 111 minutes

Cast: Juliette Binoche, Clive Owen, Valerie Tian, Bruce Davison.

Trailer: “Because I have no curiosity at all about your private lives.” (Warning: neither will you.)

Plot: Renowned artist Dina Delsanto begins work at a prestigious prep school after a long period of artistic difficulty, and encounters fiery English teacher/failing writer Jack Marcus. His immediate attraction and her distance creates a school wide debate on the artistic superiority of words or pictures. This is coupled with a routine teen drama as individual, bright students get caught up in the debate.

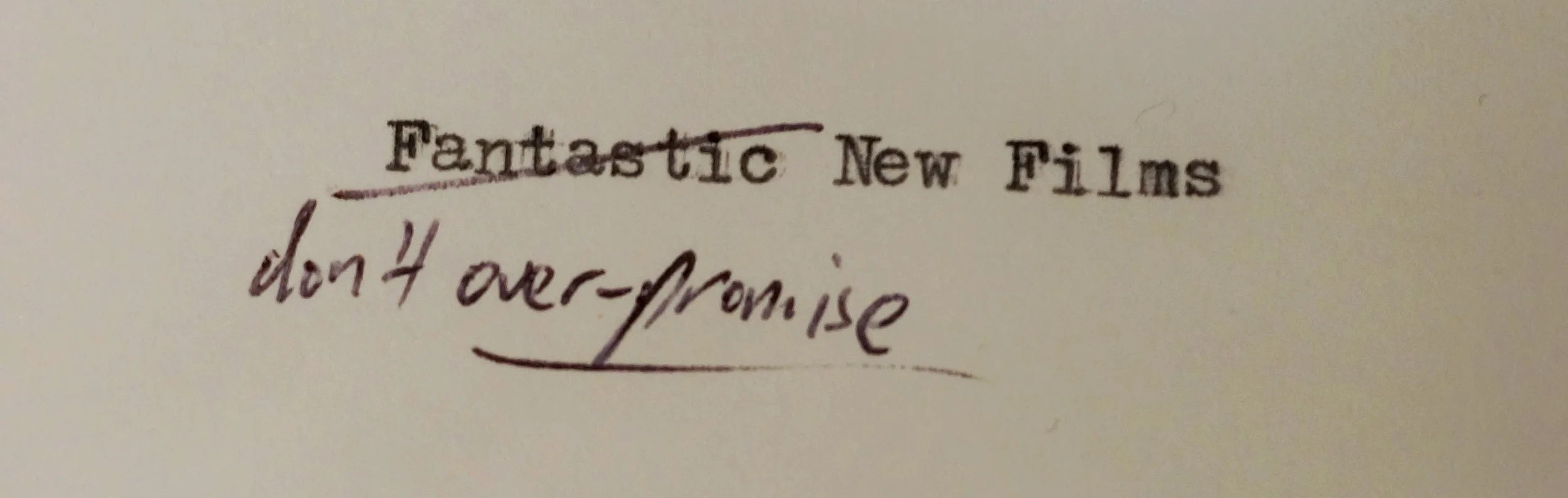

Review: Fred Schepisi’s banal and entirely expected Words and Pictures runs mostly on charm and cliché; sandwiching together three different plots that you will have seen elsewhere ad nauseam in a failing attempt to become meaningful and original. Your mileage with the film will depend entirely on whether you find the interaction of the two leads engaging, as they jump through the mandatory hoops of a Beatrice and Benedict love story. I was in a good mood, so the effect was tolerable.

The film tries to have it several ways at once; setting up Jack and Dina as artists with integrity bought low, through their respective life struggles. Jack, the writer, is meant to represent a younger John Barrymore figure – once a promising talent, but now sunk deep into alcoholism and depression. His teaching position is put in danger by his increasingly erratic behaviour and neglect of the school journal, which he had previously championed. Jack is estranged from his son, banned from a local restaurant run by a wooden duck collector (and for some baffling reason, all of the characters care deeply about this ban, to the point where it might determine whether Jack is kept on or not; as a demonstration of good faith, Jack apologises to the owner and is readmitted – on such trifles is the audience’s time wasted).

The usual beats of this sort of banal story are present; early attempt to quit drinking fails after small setback; the successful attempt is reserved for the fourth act of the film, after Jack does something truly unforgivable and after a grand gesture is forgiven. There is not much to recommend about this plot; apart from one memorable scene where Jack plays tennis with his garage door at night, drinking. Finding this suitably unchallenging, he follows his drunken logic and starts playing tennis inside, before partially destroying his house. Biographers of Barrymore noted that he frequently woke up injured with bruises and broken bones; having done something inexplicable in the light of day, or soiled himself. The tennis moment is one of the few that neatly gets at the existence of the alcoholic; the rest is glib and forgettable. Owen’s performance is adequate; he does the best with what he is given, and is able to give the impression that there may have once been something redeeming about his character which allows his colleagues to forgive what an absolute arsehole he has become.

Jack’s trajectory is changed with the introduction of Dina Delsanto as the school’s new art teacher. A famous artist, who now is unable to paint due to rheumatoid arthritis, Dina’s backstory and development stand out as the redeemable elements of this otherwise lazy film. Dina is consumed by her disability and inability to work to the standards she used to; the most gripping moments of the film focus on her quiet struggle to find new ways to paint and create work that she is happy with. To the untrained eye, many of her works are beautiful; but a subtext of Dina’s portions of the film focus on the artist as a being who is always dissatisfied with the execution of her vision. This is a punishing perspective that she brings to her teaching; driving young artist Emily to better realise her own talent. This style is born partially out of her own angst – as Dina remarks, she never turns anything down because she doesn’t know if it will be the last time, if that too will be taken away. But Words and Pictures strikes on something essential about genius; something that distinguishes those of us who are simply good at something from the mythical figures who succeed in making something great – their relentless dissatisfaction with their own work, and their compulsion to keep slashing canvases until they get close to the image that burns within them. On this level, pictures beat words – none of this drive is present in Jack’s portion of the narrative. Binoche’s performance is excellent; she disposes with the scripted shit she has been given, and provides hints of a much more meaningful narrative for her character. Sadly, she is given little space to explore it.

Lacquered over these duelling narratives is an attempt at the usual inspiring teacher plus teenage problems story; told through a disposable cast of earnest teenagers. Typically, they are as carefully selected and racially diverse as a college admissions pamphlet, and about as deep as one too. The issues they confront, in the limited time left over, are the perfunctory upper-middle class sort with character Emily as the focus; as pseudo-sexting plotline is forwarded with the Harry Potterly-named Swint as the villain. Anything that is the enemy of the earnestness the good students radiate from every pore is casually cast as the antagonist in this slight story. Ultimately it exists to provide a blurry backdrop and occasional plot point to the romance staged in front of it.

Ultimately, there is not much to be gained from the ostensible dialogue between different modes of representation; the arguments forwarded within the film consist of word out clichés (one student even quotes “anonymous” as a source in the set piece monologue, a step above citing Wikipedia or Webster’s). The film attempts to make sport of some of these clichés; deriding the statement that ‘a picture is worth a thousand words’ and limply parodying Dead Poet’s Society. But this doesn’t work in its favour, highlighting that all involved are deeply self-conscious of the empty metaphors and aphorisms it serves in their place. Music gets a passing mention, but is dropped so as not to complicate an already overstuffed (yet curiously empty) script. The truth is that to have such a debate one would need to engage with and animate a variety of aesthetic theories from Adorno, Althusser, Aristotle, or Augustine (and that, to paraphrase Footnote, is only the A’s). At points I thought that the film might be heading down the old Birth of Tragedy route; arguing that in fact film was the great artistic medium, combining as it does image, word, music, movement, and other forms in a union of the Apollonian and Dionysian. But that was perhaps me reading too much into things.

The direction, cinematography, and the overall palate of the film is what you would expect; soft, agreeable, full of whites and beaches with a dash of bold colour – rather like a children’s mobile for an adult audience. Only the paintings are sumptuous and exceptional; the artwork presented, particularly the student’s work, is interesting but fleetingly shot. In Words and Pictures there is little to remember, but much to forget.

Rating: Two stars.