Reviewed by Drew Ninnis.

Country: Italy.

Director: Sebastiano Riso.

Screenplay: Sebastiano Riso, Stefano Grasso, Andrea Cedrola.

Runtime: 98 minutes.

Cast: Davide Capone, Vincenzo Amato, Micaela Ramazzotti, Pippo Delbono.

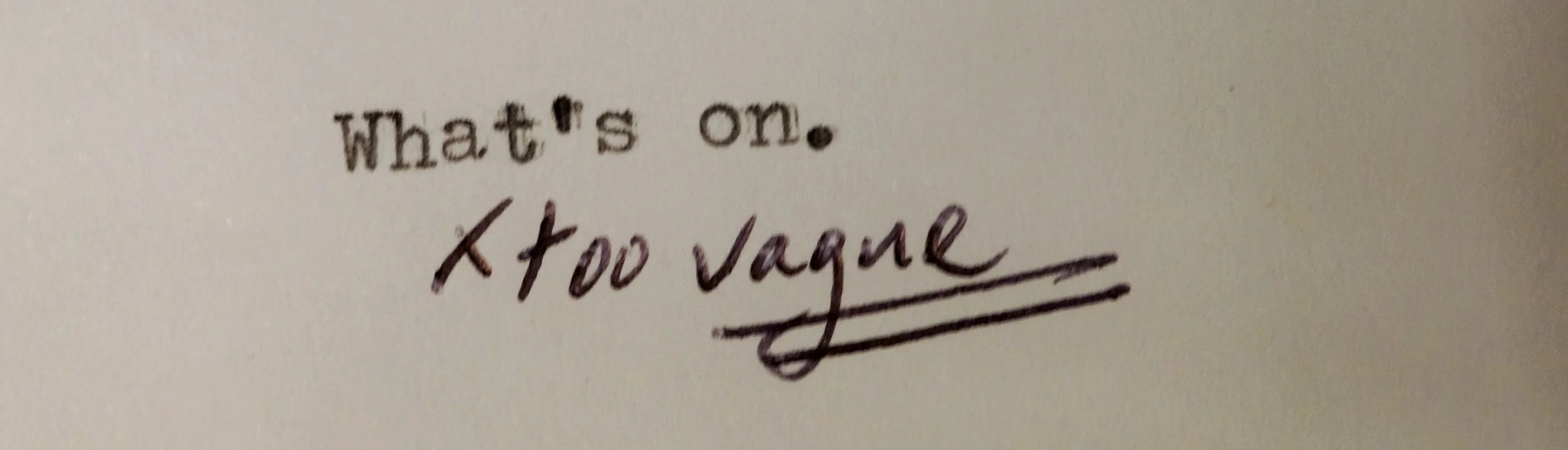

Trailer: Where a haircut passes for symbolism.

Plot: Waif Davide wanders the streets, having run away from home and his homophobic father. Falling in with a group of pimps and prostitutes, Davide quickly learns the reality of the streets, as well as how to survive. Shoplifting with his confrères, watching the performance of a drag diva, having his first sexual encounter, and seeking the protection of a local letch all feature as predictable milestones within this poorly constructed feel-bad film on its journey to the gutter.

Festival Goers? Miss it. Don’t even think about it.

Viewed as part of the Lavazza Italian Film Festival.

Review: From the depths of the tiredest art house clichés rises Darker Than Midnight (Più buio di mezzanotte); a film that would qualify as urban poverty pornography, if it weren’t such a student film debut from writer-director Sebastiano Riso. Why it was selected for the 2014 Semaine de la Critique at Cannes is baffling, possibly a product of its personal claims (the script is supposedly ‘inspired by a true story’) and its sexual politics (which constitutes the most unoriginal element of the film).

Narrating the story of Davide (Davide Capone; yes, he names his characters after the actors portraying them in that ultimate meta-pretension), an androgynous fourteen year old who has escaped his family and in particular his homophobic father, the film documents his decline and brutalisation on the streets of Catania. He is then promptly schooled in the ways of the street by a carefully selected cast of gay sexual archetypes: there is the unconvincing Marilyn Monroe impersonator, the punk, the handsome and mysterious Gallic crush, the underwear model, and the best friend, etc, etc. They occupy what can only be described as an inverted version of Augsburg’s Fuggerei, surrounded by clients and sexual-economic competitors. The expected trials and tribulations occur; a melodramatic funeral; and every clichéd representation of social ostracism one has come to expect in stereotypical, un-nuanced fare of this sort.

Why an amateurish, student film? The first hallmark is the obvious ambition of the director – despite the fundamental limitations of his budget, cast, skill – to out-Bela Tarr himself in long, sweeping takes with generous camera movement and tracking shots; lens flare and portentous shots of the sun through trees to create a simulacra of meaning; the faux-gritty realism shot in shades of red; the clinical, ham-fisted flashbacks. The whole mess is topped off by an ominous cello soundtrack, and languishing shots of poverty and despair which combine to state that any authentic sexual identity must be forged in the gutter, preferably through as much hardship and degradation as possible. Add in the quirky appearances of a mentally ill bag lady to crown the pile of clichéd elements and you have Riso’s Darker than Midnight; wearing its artifice on its sleeve, during which the director seems to genuinely be under the delusion that this hasn’t been done before, and better.

The most on-the-nose element, however, has to be the mandatory flashbacks to Davide’s life at home, where we are given a portrait of an abusive father and his helpless mother, topped off with late-film suggestion that his father was also sexually abusive. The harsh light and accompanying soundtrack Riso thought vital to these segments is obnoxious enough, material aside, with an industrial headache of noise (meant, presumably, to evoke the literal pressure within his skull of Davide’s identity crisis) over-emphasising just how traumatic these events are supposed to be. In one church scene, his father spits ‘praying will get you nowhere; he disgusts everyone.’ You’ll be worn out by the interminable flashback dinner scene, which the director slowly doles out minute by minute as David sleeps periodically throughout the film. Finally, the conflict comes to a head as predictably Davide’s glam rock sanctuary in the attic is discovered and smashed by his father, in a scene plagiarised from so many previous films. There’s even a motherly hymn hummed after the beating as the helpless wife comforts her son. Most of the tough subject matter meant to be tackled in these flashbacks is viewed only fleetingly – for example, the father administering anti-homosexual injections – as if the director loses courage or sight of what matters in his film.

The drama in the present day is equally as problematic, undermined through wobbly direction, equally wobbly camera work, and a cast not up to the task. There is the usual artificial prostitute posturing as we are introduced to the rogue’s gallery of characters we are meant to be invested in (but you won’t remember their names; I struggled to remember which one of them was missing, as they attempt to attend his funeral and are cast out). The aforementioned attempt at a long take around the Fuggerei is imperfectly shot, and quite obviously artificially blocked as extras in the background wait for the signal to start moving. A diva appears in a Pink Flamingos concert moment, with a closely shot crowd to conceal budget limitations. One of the gang is a faintly ridiculous underwear model, muscularly towering over the rest with his chiselled jaw and so manicured one wouldn’t believe he had spent even a minute on the streets. The rest are as unconvincingly cast and shrill in their uncomfortable roles as a result. There’s some blush applied to approximate the bruises from the inevitable beating; there are annoying shots of a light glaring in a mirror, which is meant to read as innovative but comes off as badly composed; there’s more lens flare than a J.J. Abrams film. It’s overwrought, there’s much whispering into character’s ears to indicate the furtive secrets of darkest sexuality, there are very distancing techniques that Riso obviously believes are the makings of a unique directorial style but through their incoherency aren’t.

Penultimately, there’s the dialogue itself. 'I think you haven’t fucked in your whole life' Marilyn Monroe lords over our inexperienced, mousey protagonist. ‘How do you feel when you sing?’ he asks the Diva, ‘I feel free’ she responds. A symbolic, corpulent protector in white turns up with an incomprehensible singing metaphor pick-up line and the advice 'If you need me I’m there every day. Except Sunday.' What hypocrisy could that possibly be a critique of. And when the cello doesn’t kick in, a faux-Philip Glass pensive piano does.

Ultimately, the crass symbolism broke my patience. Davide’s face and epicene looks are highly fetishised, and used as a stand-in for quiet purity throughout the film. There’s the record aficionado who cannot speak, and only listens to the first thirty seconds because he believe the record might otherwise be ruined. There’s the slow, panning shot meets inventory of a room while Davide is sexually taken by his protector (another shot plagiarised from a thousand other films), there’s the sloppy image of said protector all in white. There’s the group of friends sleeping crammed into a clown car, in a Paul Smith-like advertiser’s dream. There’s the violence of the first time filmed through the corrugated glass window of a door David is pressed up against. There’s the Crying Game meets Lady Macbeth act as Davide tries to scour himself in the sink afterwards. There are the close-ups of the dead friend’s happy, innocent photo set up in the second act of the film, like Chekov’s Polaroid. Davide sees his future in a closet full of these photos of lost boys, in the straw that broke the camel’s back for me personally (your mileage may vary).

There’s the pretentious final title card and the unearned silence that closes the film, as the director is mistakenly taken with the idea that he has produced something profound rather than photocopied. Judging by what he has chosen to present on screen during Darker Than Midnight, we need hear no more from debut director Sebastiano Riso.

Rating: One star.