Reviewed by Drew Ninnis.

Country: Italy

Director: Daniele Luchetti

Screenplay: Daniele Luchetti, Sandro Petraglia, Stefano Rulli, Caterina Venturini.

Runtime: 106 minutes.

Cast: Kim Rossi Stuart, Micaela Ramazzotti, Samuel Garofalo, Niccolò Calvagna.

Trailer: “Strange goings on in my father's studio.”

Plot: Guido is a young, talented sculptor who is dissatisfied with his traditionalist work and his teaching – attempting to branch out in to the avant-garde, but with little success. After a bruising encounter with the critics at an exhibition, he selfishly demands time and space from his loving family and his fiery wife. Sick of their unhealthy relationship, his wife Serena takes their two young boys on a feminist retreat in the south of France – occasioning a sunlit transformation of their lives, and their return to their father.

Festival Goers? Must see. Film of the festival.

Viewed as part of the Lavazza Italian Film Festival 2014.

Review: Daniele Luchetti’s Those Happy Years (Anni felici) is a superb and moving film; set in the 1970s, it captures the spirit of an era and the struggle of an artistic family. There is not a clichéd moment present throughout the film; on the contrary, some moments are so beautiful and unique they take the breath away. Yet the film is also funny and warm, drenched in the passion of its main characters and told from the perspective of a young Dario (Samuel Garofalo) who will himself one day grow into an artist like his father, Guido (Kim Rossi Stuart). The film is enchanting, and the minutes and the hours melt away like the concerns of another life.

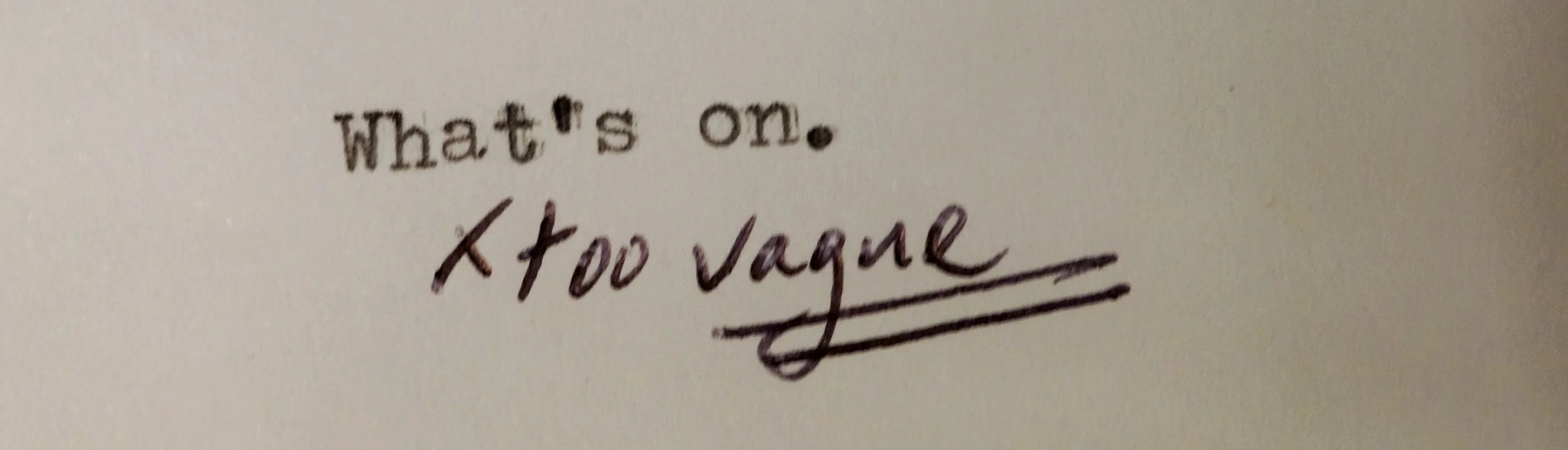

The narrative follows artist Guido, an exceptionally talented sculptor, and his supportive but justifiably possessive wife Serena (Micaela Ramazzotti). Eschewing traditional forms of sculpture (as the narrator remarks, ‘it came to him easily so he thought it was wrong’) and attempting to place himself at the avant-garde of Italian performance art, Guido has daring and conceptual ambition but is unfortunately judged by the critics as too confused and sensationalist to merit serious consideration. Unserious in his affairs with his models, he struggles to fit the demands of a family and conventional domestic life; seeking refuge in a worn ideology of socialism and free love to justify his recklessness. ‘He had three wives, four sons. No one told Picasso what to do!’ Guido complains. His children, perpetually underfoot at his studio, ask ‘can we at least smash the car outside?’ to which he replies ‘sure here are some tools.’ But his ability to draw on these sources of inspiration is shallow, as a misjudged (but spectacularly, hilariously staged and filmed) exhibition of performance art is panned by the broader art world. Instead, it is Guido’s wife who accidentally attracts the praise and the eye of the critics for her unintentional role in the piece.

But Those Happy Years is only incidentally the story of Guido; indeed, it is more fully the story of Serena, who undergoes a transformation from jealous wife to transformed sexual and spiritual being. Fretting over his affairs, Serena’s mother remarks ‘Let him have his fun. You gave him two children, you’ll always beat the others.’ Yet this is not enough for Serena, and she follows him to Florence for the aforementioned performance art and exhibition, despite the prohibition from Guido. The performance itself is exactly what you would expect from the period; encircled by his four models, the artist is painted in bright primary colours and signs them, giving his blessing, by pressing his hands on their collars. An acolyte demands seven supplicants from the audience; asking them to strip and receive his blessing. Captivated by her husband, Serena strips in front of her children and presents herself to the startled artist; on receiving the blessing, the audience breaks into applause – much to the consternation of her husband. Bearing his wrath afterwards, Serena pleads ‘I took you literally!’ to which he responds ‘it was a provocation! I wanted the audience to confront their inability to free themselves!’

Everything that is wonderful about this film is evidenced in that single, bravura scene – one of several impressive moments within the film. Shot ceremoniously, pompously, Luchetti leavens the ridiculousness of the performance’s pretentiousness with tight shots of the faces of Serena and Dario, as they watch enthralled. The cinematography creates an amusing parody of The Holy Mountain, a consummate product of the 1970s ideological mystification and symbolism that Guido is going for, while evoking the period through a clever use of colours and filters that almost place the audience within a warm, oranged Polaroid photo of the scenes. Yet the scene is hilarious, funny for its mockery of a certain wild enthusiasm of the times, and yet wrenchingly, emotionally beautiful in its evocation of Serena’s love and the wide eyes of their children – adrift in an adult world, but protected by their mother, who is only marginally better at navigating its bruising demands.

Just so the audience knows that this was not luck, but real skill, Luchetti performs this trick again and again throughout the film – plucking magical scenes out of the air, soaked in a beautiful confusion of emotions and a childhood yearning for those sun-dappled days. When Dario finally gets his hands on a much coveted camera, and joins his mother and his brother on a feminist retreat full of young children, he recreates his father’s performance with the joy of a child – creating an iconic set of scenes significant to the director, and known as ‘erotic dust.’ The boys and girls paint themselves, run around, create chaos on the beach in the fading light – transforming his father’s lifeless work into something transcendent. ‘Everything that’s beautiful has to be new,’ Guido explains to his children, arguing the doctrine he yearns to achieve. Yet Dario creates something extraordinary precisely because it is rooted in what is old, lost, commonly understood, and yearned for. ‘We’d lost our innocence or found it,’ the narrator remarks, as Serena has her first experience outside her marriage and learns to live as an independent being, while her children shed something of themselves in the beautiful summer. These scenes are so beautiful and warm they make my heart swell in recollecting them. There is another wonderful shot of them sleeping in deck chairs, on the lawn, as a time lapse shows the movement of the shadows of the trees and the shifting light of the moon. Beautiful.

When they finally return to Guido, having learned of the failure of his performance, things have changed. Confronting a critic, Guido is told ‘your work is fake, a pretence of being, naive’ and ‘to provoke isn’t to display naked bodies but floor people with them.’ It is the harshest lesson for an artist, but the one that is most important – and, it seems, one that Luchetti has taken to heart over the course of his distinguished career. The family is momentarily split by the events of the summer; with both Guido and Serena struggling to understand the changed terms of their relationship. The film returns again and again to a seaside scene, one that is only fully understood in the closing moments of the film – where a defiant Dario screams ‘you’re all assholes! huge assholes!’ to his quietly feuding parents. He relates it as ‘the day they realised I was there,’ bringing the film full circle and touching a personal note within Luchetti’s work. The performances of his four main cast members, and the qualities he manages to elicit from them, are outstanding – with Micaela Ramazzotti undoubtedly stealing the show as the open, vulnerable Serena. Some of Luchetti’s unconventional directorial choices mar what is otherwise a perfect film – such as a fourth wall-breaking car scene with Serena, or the decision to run highlights of the film over the credits. But these missteps are more than forgiven.

Ultimately, Those Happy Years succeeds on the impossible terms it sets for itself – evoking those lost summers of pure joy and discovery. More than this, the film unsettles half-memories of childhood and growing into adulthood from within the audience, allowing them to rise to the surface and unfold within the spaces created by the film. On looking at some works of contemporary art, Dario complains to his father that ‘I can do that,’ to which he responds ‘you can now, but you hadn’t thought of it before.’ It is poignant for me, because I remember having the exact same conversation with my father in an art gallery many years ago.

But while Luchetti’s film also goes down, deep into a personal and resonant experience, it can also take flight and move upwards – achieving something above and beyond our experience, something that those perfect works of art capture from the spheres that seem outside of a single human experience. Separated from Serena, Guido returns to the traditional and crafts something in his studio that startles all who come to see it – a giant, beautiful sleeping figure. In a scene so deeply reminiscent of the transcendent whale scene in Bela Tarr’s masterpiece, Werckmeister Harmonies, Serena paces around the giant clay sculpture in wonder. ‘Who is it?’ she asks, ‘It is your absence’ Guido replies. Beautiful.

The auteur is alive and well in contemporary Italian cinema; and personally, I will be placing Luchetti’s Those Happy Years on that special shelf in my heart occupied by Michelangelo Frammartino’s Le Quattro Volte, and Paolo Sorrentino’s La grande bellezza. The same critic, upon viewing Guido’s new work, remarks ‘if you think that a work looks at you, you must talk about it honestly; you owe it that.’ Those Happy Years is just such a work; remarkable, and touching on a personal level, but revealing something meaningful far beyond it.

Rating: Five stars.